Europe's economic challenge not just about Greece

- Published

- comments

Mr Juncker (r) declared: "Greece is and will remain irreversibly a member of the euro area"

There was a moment in 2010 when I was in a lift inside the Berlaymont building in Brussels - the headquarters of the EU's executive branch.

Two colleagues entered and one said to the other, "I hear Greece has been saved." The other man said it was "great news".

It felt as if the relief of Athens had just been reported in a despatch from a distant frontline.

Little could the officials know how long the Greek crisis had to run and how it would come to dominate a string of late-night emergency meetings.

At times it seemed that the future of the EU itself was tied to the fate of a country that made up just over 2% of the eurozone's economy.

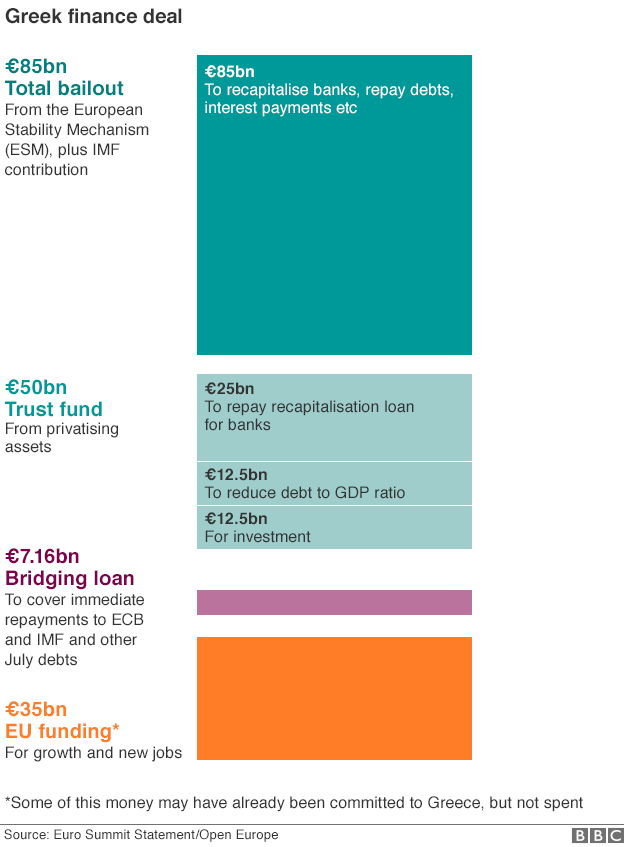

Now Greece has secured a third bailout, worth 85bn euros (£60bn) in loans over three years.

Last week the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, triumphantly declared: "The message is loud and clear; on this basis Greece is and will remain irreversibly a member of the euro area."

'Unsustainable' debt

A few hurdles remain. The deal still needs approval from the German Bundestag on Wednesday.

Angela Merkel will get the votes - the only question is the size of the rebellion against the bailout.

Christine Lagarde: "I remain firmly of the view that Greece's debt has become unsustainable"

The Germans do not like the fact that the International Monetary Fund is not yet on board.

The head of the IMF, Christine Lagarde, said: "I remain firmly of the view that Greece's debt has become unsustainable."

The European institutions believe Greek debt will reach 201% of GDP some time next year.

Sooner or later the question of Greek debt will have to be addressed. It is unlikely a portion of the debt will be written off but there may well be an agreement to extend current loans and to lower the rates of interest.

In the meantime German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble has promised eagle-eyed attention, insisting that the reforms are implemented by Athens "line by line".

There may well be political instability in Greece. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras will struggle to keep his party together and he could decide to call elections in the autumn.

That will inject fresh uncertainty into the drama for a few more weeks.

Flat-lining France

But, for all the uncertainties, it appears a Greek chapter is closing. For a long period the future of Greece was cited as one of the dangerous unknowns hanging over the European economy.

As the Greek crisis subsides the focus returns to the wider health of the eurozone economy.

French economic growth has been anaemic

In many respects it should be the best of times. Interest rates are low, the falling value of the euro has boosted exports, the European Central Bank since March has been buying bonds on an industrial scale and energy prices are down.

And yet the eurozone economy splutters. There is a recovery - the eurozone is growing at an annual rate of 1.3% - but it is patchy.

In the second quarter of the year France and Italy, which account for 40% of the eurozone economy, flat-lined. Italy which had only recently emerged from recession fell back, managing growth of just 0.2%.

Unemployment (June 2015)

EU 9.6%

Eurozone 11.1%

Greece 25.6% (April)

Spain 22.5%

Italy 12.7%

France 10.2%

Germany 4.7%

Source: Eurostat, external

The German economy is turning in a solid performance based on exports. But it is vulnerable to a slowdown in China and Japan, where economic growth shrank in the second quarter of the year.

The signs are that the eurozone recovery is losing momentum, with consumer confidence weak. The European Central Bank said the "balance of risks to the economic outlook for the euro area was seen to remain on the downside".

Difficult and disruptive

The eurozone economy is still smaller than it was in 2008.

It remains an economy in fragile health. Unemployment is still above 11%, nearly double that in the United States. Even in fast-charging Spain, unemployment is stuck above 22%.

And in many countries like France what new jobs there are tend to be temporary.

Persistently high unemployment in Spain presents a challenge for PM Mariano Rajoy

At some moment the benign international climate will change. The Chinese economy could slow further and so weaken demand for high-quality imports like German cars.

Energy prices may increase again and it is unclear what impact the expected rise in US interest rates will have.

The fundamental challenges to the European economy remain - how to innovate; how to reduce regulations that protect powerful interest groups; how to increase competitiveness in a global economy; how to ensure energy remains cheap; how to modernise - an often difficult and disruptive process.

In the nearly six years of the Greek crisis much has been written and said about modernising the European economy - about Europe living up to its potential.

The challenge remains.

- Published21 August 2015

- Published16 August 2015

- Published3 August 2015

- Published22 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015