Migrant crisis: Opponents furious over new EU quotas

- Published

BBC reporters describe the scene at some of Europe's migrant hotspots

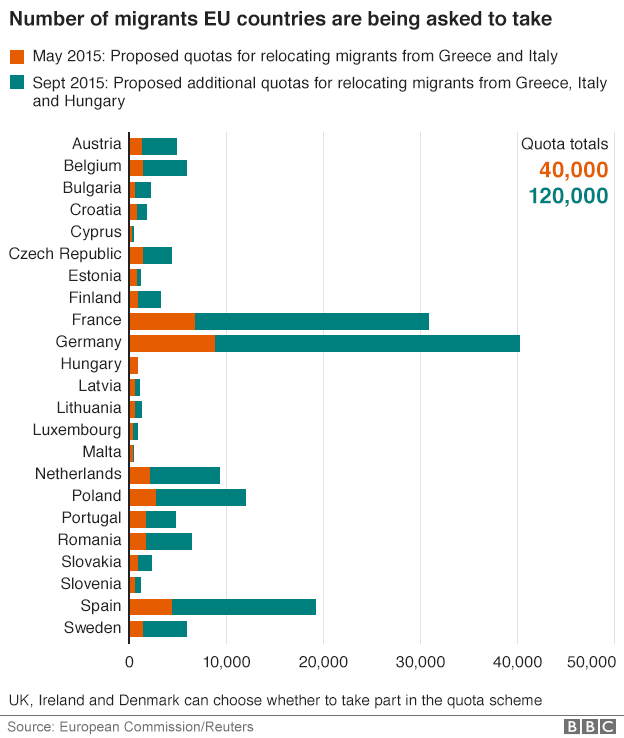

Central European countries have reacted angrily after plans to relocate 120,000 migrants across the continent were approved by EU interior ministers.

Under the scheme, migrants will be moved from Italy, Greece and Hungary to other EU countries.

But Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary voted against accepting mandatory quotas.

Czech President Milos Zeman said: "Only the future will show what a mistake this was."

The BBC's Europe correspondent Chris Morris says it is highly unusual for an issue like this - which involves national sovereignty - to be decided by majority vote rather than a unanimous decision.

The scheme to take in migrants appears on the surface to be voluntary, he says, although countries are likely to be given little choice in the matter.

In the latest reaction:

Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico says he will not accept the new terms and will not "respect this diktat of the majority"

Czech Interior Minister Milan Chovanec has tweeted:, external "Very soon we will realise the emperor has no clothes. Today was a defeat for common sense"

Radio Prague reports that the Czech Republic could seek to take the matter to the European Court of Justice, external

In Latvia, whose interior minister backed the move, hundreds of people have marched against the quotas

Hungary will respect Tuesday's decision, a government spokesman says

Under the EU's rules, a country that does not agree with a policy on migration imposed upon it could have the right to appeal to the European Council.

But Luxembourg Foreign Minister Jean Asselborn, who chaired the meeting, said he had "no doubt" opposing countries would implement the measures.

Read Tuesday's developments as they happened

Follow BBC correspondents covering the crisis on Twitter, external

Finland abstained from the vote. Poland, which had originally opposed the proposal, voted for it.

"We felt that it was much better to negotiate, to negotiate all these conditions, which for us are important," Poland's Europe minister, Rafal Trzaskowski, told the BBC.

"We preferred to be an active member of this debate."

The scheme must now be ratified by EU leaders in Brussels on Wednesday.

Who are the 120,000?

All are migrants "in clear need of international protection" to be resettled from Italy, Greece and Hungary to other EU member states - Hungary will also take its share

15,600 from Italy, 50,400 from Greece, 54,000 from Hungary, though it is unclear how many are still in Hungary

Initial screening of asylum applicants carried out in Greece, Hungary and Italy

Syrians, Eritreans, Iraqis prioritised

Financial penalty of 0.002% of GDP for those member countries refusing to accept relocated migrants

Relocation to accepting countries depends on size of economy and population, average number of asylum applications

Transfer of individual applicants within two months

Under the plan, Hungary will have to take in a share of migrants. Had it not opposed the scheme, it would have been exempt.

Hungary's anti-immigration Prime Minister Viktor Orban could present his own proposals before EU leaders on Wednesday.

Mark Lowen reports from one pressure point in Edirne, on the Turkey-Greece border

The UN refugee agency said the scheme would be insufficient, given the large numbers arriving in Europe.

"A relocation programme alone, at this stage in the crisis, will not be enough to stabilise the situation," , UNHCR spokeswoman Melissa Fleming said.

The number of those needing relocation will probably have to be revised upwards significantly, she said.

The UN says close to 480,000 migrants have arrived in Europe by sea this year, and are now reaching European shores at a rate of nearly 6,000 a day.

A crisis like no other - Chris Morris, BBC News, Brussels

Criticism is already ringing out from countries that voted against the relocation scheme, but under EU law they are now obliged to take part. It is highly unusual - unprecedented, really - for a majority vote to be used in a situation like this, which involves basic issues of national sovereignty.

But the European Commission says it is determined to enforce what was agreed. What's not yet clear is what will happen if any country simply refuses to comply - and that has certainly been the suggestion from some capitals.

Will financial sanctions be sufficient? It is another sign that this crisis is testing European unity like no other.

After the meeting, German Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere said: "Today is an important building block, but no more than that."

A statement from the European Commission, external said foreign ministers would now discuss reforms to the Dublin regulation, which demands that migrants register as refugees in the first EU country in which they arrive.

The UK has opted against taking part in the relocation scheme and has its own plan to resettle migrants directly from Syrian refugee camps.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.