Paris attacks: Investigators face huge task

- Published

- comments

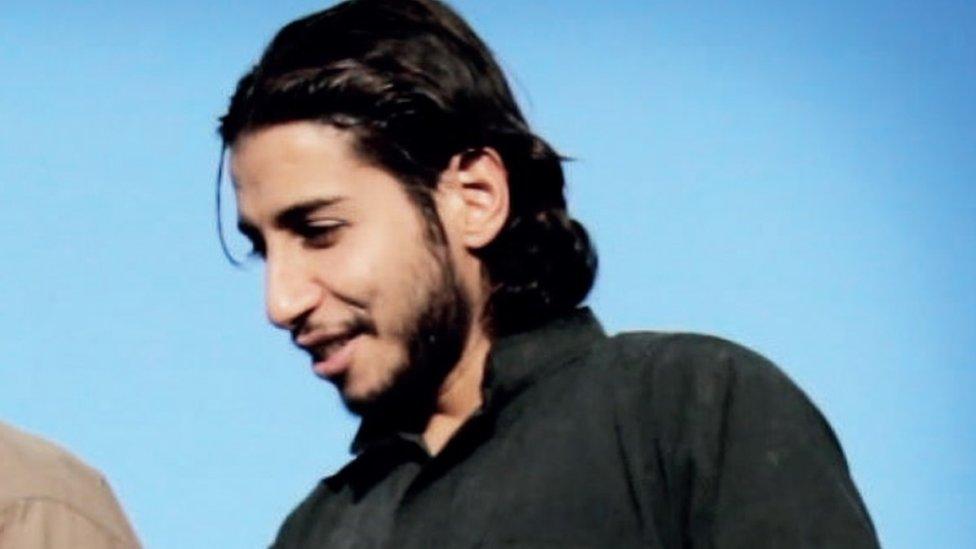

Abdelhamid Abaaoud died during a police raid on a flat in Saint Denis

News that Abdelhamid Abaaoud, believed to be the ringleader of the Paris attacks, had died during a French police raid came as a welcome win for investigators.

At the same time though, they realise the Belgian jihadist's whereabouts was just one strand in a complex and evolving investigation being pursued under the enormous pressure created by the knowledge that their enemy may launch murderous follow-on attacks at any moment.

On Wednesday evening, Paris prosecutor Francois Molins caused consternation when he revealed that "a new cell was neutralised" during the bloody raid of a flat in Saint Denis and that "this team would have been able to carry on other attacks".

Suddenly we realised this was not those who'd escaped Friday's atrocities and that even if Abaaoud was proven to have been there, it was a different cell, heavily armed, that according to some official briefings was about to perpetrate a massacre in the financial district of La Defense.

So we have received a salutary reminder that the journalistic narratives of an "eighth man" or an "escaped mastermind" often get in the way of understanding what is happening in a case like this.

It might be done with integrity (based on official sources leaking information for their own reasons) or it might be no more than a social media echo chamber where some speculation soon becomes a "fact" bemused investigators are then quizzed about.

Their inability to answer some of these questions might be seen as suspicious, whereas in fact it is no more than puzzlement.

Hundreds of swoops

The question of how many people the authorities are looking for is in itself a complex one because the number is being added to all the time.

When Mr Molins revealed on Wednesday, for example, that one of Friday's Stade de France attackers and one of the Bataclan theatre killers remained unidentified, it indicated a certainty that once those identities had been established it would generate additional lines of inquiry, raids and quite probably arrests.

There have been so many of these police swoops - several hundred since Friday - that one has to ask whether they are simply taking this opportunity to bring in all sorts of jihadist suspects or whether the list of people they are looking for is much larger than we might suppose.

The number of people being sought by the French security forces is still rising

After all, there are all manner of enablers or supporters who may be questioned for helping jihadist cells or simply complicit by their failure to report certain facts, even if they didn't have a direct role in the attack.

Fanning the flames of uncertainty to achieve maximum effect, the Islamic State (IS) group on Thursday released two videos promising more attacks.

"Christian countries," one speaker warned, "suicide bombers are present in your country in their tens, or rather in their hundreds."

While one might dismiss this as mere propaganda, it's clear there are hundreds of returned jihadists in Western Europe, even if relatively few of them would be prepared to carry out an IS "martyrdom operation".

Returning to the central issue of the 13 November perpetrators and their immediate network, there are reasons for believing it is considerably bigger than the eight men who carried out the attack.

The day after these atrocities, the Iraqi government revealed it had warned France that 25 IS members were on their way from Syria.

Now this may be wrong, not least in that it has not been proven that all of last Friday's attackers were recently arrived from the Middle East, but the discovery of a new, but connected, cell in Saint Denis, and of a car full of guns and explosives in Bavaria (a few days before Paris, but known to have been heading there), provide strong indications that Abaaoud and IS were preparing something more extensive than the eight-man assault that took place.

Ugly necessity

The news that Abaaoud was indeed one of those who died in the Saint Denis raid of course creates new concerns among intelligence agencies. How could an IS "poster boy" who had appeared in the movement's videos and been on counter-terrorist watch lists across Europe have made his way to Paris undiscovered?

As if this were not already disturbing enough, the authorities have added to the dread. French Prime Minister Manuel Valls saying: "We must not rule out anything," has suggested that IS may be preparing to use chemical or biological weapons in its attacks.

French police have been authorised to carry their firearms whether on or off duty

French police have been authorised to carry their firearms at all times, on or off duty.

Reminding the public of these concerns (IS is believed to have used mustard gas chemical agent against opponents in Syria) may be no more than an ugly necessity at this time.

But of course Mr Valls was on Thursday guiding legislation for a three-month extension to France's state of emergency (giving sweeping powers to the authorities) through parliament.

As in the UK, this involves a difficult public debate about intrusion into people's privacy and the suspension of some cherished civil liberties.

End of Abaaoud

Whatever our uncertainties about the investigation, we have learned enough already to understand that it is a widening dragnet that is expanding across Europe. Multiple raids in the Molenbeek district of Brussels have been generated by intelligence coming from Paris, as well as arrests in Germany.

Each intervention is producing new leads, and there are investigative or intelligence teams across Europe now re-examining earlier incidents, mapping individuals that might be connected to the latest discoveries.

It is a huge task and little wonder that the police or intelligence bureaucracies are taking their opportunity to push for bigger budgets and more people.

Hundreds of jihadists have returned to Europe from the Middle East

At some point, all of this will peak and the number of leads or files being closed off by investigators will start to exceed the new ones being pursued.

Many suspects on the outer edges of the conspiracy or simply in the wrong place at the wrong time will be released. There may even be some sense of relief.

But of course that will simply mark the end of the story of the Abaaoud network and the 13 November attacks.

It would be foolish to think that Islamic State will not be trying to reinvent this model all over again with new teams of operatives dispatched to spread death on the streets of Europe.