Islamist extremism: Why young people are being drawn to it

- Published

A young man is handcuffed during an anti-terror raid in Sydney in October

"This should be concerning to everybody," said Catherine Burn, police deputy commissioner for New South Wales.

She was speaking after a 15-year-old boy was charged with conspiracy in connection with an alleged terror plot in Australia.

He is one of the latest teenagers to be linked to activity by Islamist extremists around the world.

Last month, reports said one of two girls who ran away from their home in Austria to join the so-called Islamic State in Syria had been beaten to death while trying to escape. She was 17.

Her 15-year-old friend is believed to have been killed in fighting in 2014.

While the majority of jihadists around the world are not teenagers, official figures show that their involvement in violent Islamism is growing.

The number of under-18s arrested for alleged terror offences in the UK almost doubled from eight to 15 from 2013-14 to 2014-15. The total number of arrests for all age groups was 315 - an increase of a third on the previous year.

Shamima Begum, 15, who left London for Syria, is thought to have been radicalised - at least in part - over the internet

Experts say this bears out fears that more and more young people are being drawn to extremism, with followers in their early teens among them.

"We are seeing this kind of thing happening more and more with the rise of Islamic State," says Charlie Winter, an expert in jihadist militancy.

"And it is not something that is coming about by mistake."

Social media

The main target for groups like Islamic State is said to be young people between 16 and 24 years old.

However the radicalisation process can start as early as 11 or 12, says Daniel Koehler, director of the German Institute on Radicalization and Deradicalization Studies (GIRDS), external.

Police believe Farhad Jabar, 15, who killed a police worker in Sydney, had links to terrorism

Younger members are less valuable in terms of potential to carry out terror operations, he says, but they are used to spread ideology and influence others.

And they are easier to access. "Adolescents and teenagers are indeed easier to impress and lure into relationships with recruiters."

Much of the recruiters' work is done online.

"The internet is essential…. IS produces an average of 30 to 40 high-quality videos per day in almost every language," says Mr Koehler.

"They have an estimated Twitter network of 30,000 to 40,000 accounts, and guides for carrying out jihad or how to join IS are easily available online."

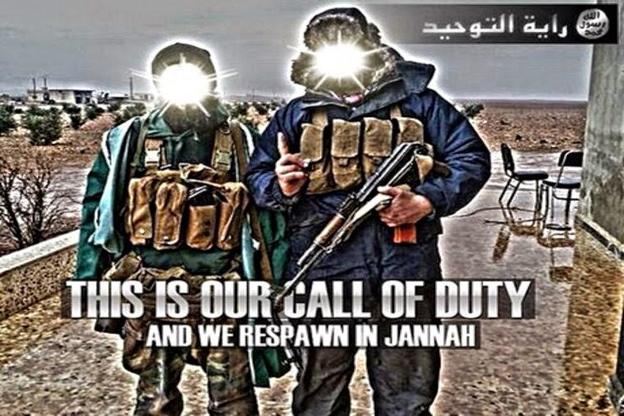

IS has used imagery from games such as "Call of Duty" in their recruitment

They have also been shown to heavily rely on other social media platforms such as Ask.FM, external, which are visited by a large proportion of younger users.

Counter culture

But it is not just the volume of content which is driving membership.

"While the internet does play an important role, what is different with IS is that it is much more outward facing," says Mr Winter, a senior research associate at Georgia State University.

"There is more accessibility and more interaction."

He says one of the greatest draws for young followers is the promise of belonging to a collective.

"IS is really trying to push this idea of a counter culture. They have crafted this idea of state building, of democratic jihad."

Islamic State fighters are encouraged to share their stories to boost recruitment

This aspirational nature can appeal to some adolescents who have high ideals and ambitions but are frustrated by their families or societies.

The feeling of marginalisation also drives membership, says Mr Winter.

"Ideology is very important but it is also about how people feel about the society they live in.

"Real or perceived grievances in the hands of a recruiter can reach fever pitch."

'Impressionable'

While the internet is certainly an important tool for recruiters, both direct, real-life contact with radical groups in their home countries is equally vital.

"What we have seen a lot of times is people being enlisted by friendship groups," says Mr Winter.

"It's not just online. For every individual it is as much about knowing someone who has been to fight."

Members who have fought in Syria are encouraged to share information as a way of bringing other people in.

Experiences are whitewashed to hide the iniquities and hypocrisies of the group's mission.

Young people are particularly impressionable when they hear these stories, Mr Winter says.

And the stories can be found in schools, friendship groups and communities as easily online for those that know where to look.

Mr Koehler says young people are more accustomed to seeing violence in the media than adults, and this plays a role in their growing involvement in violent Islamism.

"But in the end it is about personal backgrounds and trajectories combined with opportunities and situations," he says.

"It is about when and how you come across a certain ideology and group, and what you are currently looking for in your life."

- Published2 October 2015

- Published30 July 2015

- Published9 October 2014