Sangin: Kabul and Nato's failures laid bare

- Published

Afghan forces are under intense pressure from the Taliban in Helmand

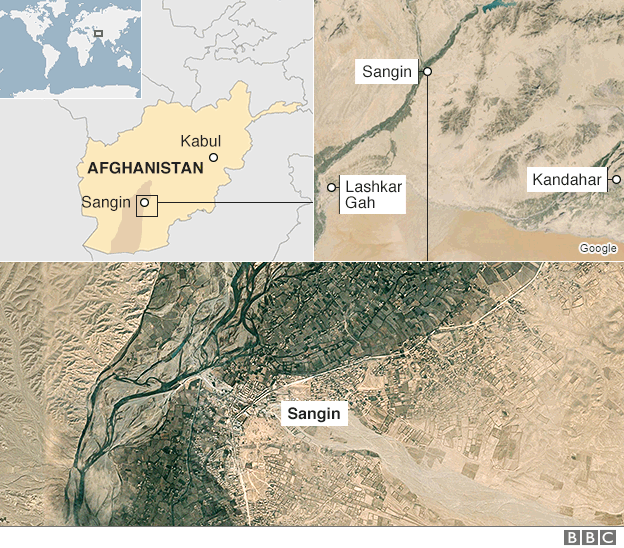

The grim strategic geography of Afghanistan, the province of Helmand and towns like Sangin and Lashkar Gah, is back in the headlines.

They are places etched into the collective memory of the British military, which suffered over 100 combat fatalities in and around Sangin, almost a quarter of all those killed during Britain's Afghan intervention.

Now the Taliban has swept across Helmand, taking control of all but two of its districts, and pushing Afghan forces in Sangin to the brink.

The Taliban surge, not just in Helmand but in a number of other provinces, has highlighted the dysfunction at the heart of the Afghan government and thrown the continuing problems of the Afghan military into high relief.

The Taliban resurgence is as much a product of the turmoil in its top leadership as anything else, with different factions vying for power and seeking to demonstrate their pre-eminence by displays of military prowess.

The Taliban has been carrying out some of its boldest attacks in years

The fact that the so-called Islamic State organisation is slowly putting down roots in the turmoil is also worrying Western military planners and adding a new dimension to the Afghan conundrum.

When Nato-led combat operations ended in Afghanistan in 2014, the stage was set for the Afghans themselves to make the running.

It was believed that the Afghan military would be able to stand on its own two feet, albeit with continuing advice from Nato specialists.

Nato established a new mission dubbed "resolute support" to train, advise and assist the Afghan forces.

But while fighting bravely in many circumstances, the Afghan security forces continue to display serious shortcomings.

Their logistics are poor. Equipment is pilfered or sold. The Afghans lack serious air support of their own. The first pilots for a squadron of Tucano ground attack aircraft have only just completed their training in the United States.

But the crisis in Sangin has also demonstrated the weakness of the central government in Kabul.

It has been unable to establish a clear political consensus. Tensions in parliament mean that the country is still without a full-time defence minister. And the governmental system as a whole is beset by cronyism and corruption.

The Taliban surge also means that Nato has to confront some grim realities about its own strategy.

The initial year of the Resolute Support mission was based upon a hub-and-spoke operation centred on Kabul with four regional centres providing the training on the ground.

Curiously, Helmand was not one of them; advisory teams, including one British, have had to be despatched at short-notice to try to galvanise the Afghan military on the ground.

Why was Helmand left out? Probably because Nato, despite all the protestations about providing whatever forces might be needed, just does not have sufficient troops at its disposal.

Will Nato strategy change in the wake of the Helmand fighting? Probably not. In fact, Nato had already shifted gear in the wake of the fall and recapture of the northern city of Kunduz back in October.

The original plan for 2016 was to focus the effort largely in Kabul. Now the more dispersed training operation of 2015 will continue for another year.

While the Americans may blur the boundary between counter-terrorism and fighting the Taliban to give additional support to the Afghan forces (and US air power in particular will be crucial), there is little appetite elsewhere in the alliance for a renewed combat mission there.

The crisis in Afghanistan raises broader question about the whole trajectory of Western military interventions over recent years.

While the exact circumstances differ, many of the questions and dilemmas remain the same from Afghanistan, to Libya, Syria, and beyond.

There has frequently been an inability to define clear and achievable strategic goals and then to provide the necessary resources to achieve them.

The attention span of Western powers and their publics is limited. Rhetoric greatly exceeds commitment.