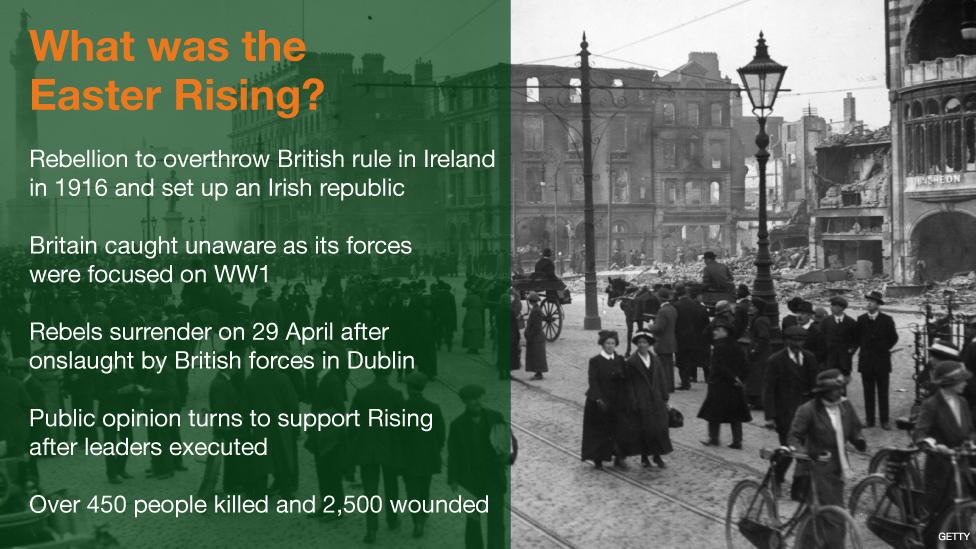

The difficulty of marking Ireland's 1916 Easter Rising

- Published

Road blocks and British troops on the streets of Dublin in 1916

Fergal Keane looks at Ireland's violent Easter Rising, and how it is being marked as its centenary approaches.

Almost every state exists because of violence. Over the centuries world wars, civil wars, revolutions and genocide have helped create nation-states across the world. Great empires were built on the violence of superior firepower.

Yet commemorating the violent birth of the modern Irish state raises difficult questions because the legacy of killing is so very recent, and because of the deep divisions which remain on the island.

For Brona Ui Loing, whose grandfather and two great-uncles took part in the Rising, this is a moment for celebration. "I think they were very brave men to do what they did… they wouldn't have been well-armed and I just think the fact that they all marched to Dublin… they are the bravest people I know.

Brona Ui Loing's forebears fought with the rebels

"I don't know if we would have been as brave in our turn if we had been asked to do it."

In the Republic, where the population is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, it is easier to revere the leaders of the 1916 rebellion as founding fathers. For Ulster Protestants they have historically represented the old fear of destruction at the hands of Catholics.

More about the Easter Rising

The fact that the rebels rose up without asking the people of Ireland what they felt, and did so in defiance of their moderate comrades, tends to be glossed over in the official remembrance of a modern democratic Ireland.

Yet it is precisely this belief in the right of a self-selecting group to strike on behalf of the Irish people which is still claimed by the republican dissidents who recently murdered prison officer Adrian Ismay in Belfast. For three decades it was used by the Provisional IRA to attempt to provide legitimacy for their campaign of violence.

Read more: Six days of armed struggle

The anniversary of the Rising passed without significant attention in the Republic during the years of the Troubles. Fearful of stirring up republican sentiment, the Irish state preferred a low-profile approach.

But with the end of any large-scale violence in Northern Ireland, it became possible to commemorate without the risk of being seen to offer succour to the IRA.

Former Irish PM John Bruton cautions against celebration

However, the former Irish Prime Minister, John Bruton, argues against what he sees as a "celebratory" tone around the 1916 centennial: "That murder indicates how dangerous it can be to commemorate something without properly understanding that what one is commemorating is the killing of a large number of people in Dublin."

Mr Bruton points out that for every rebel killed in 1916, three civilians died.

"It is important that in remembering and commemorating what happened that we don't glorify or justify it."

British soldiers sniping near Dublin's quays

Both major political parties in Ireland, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, as well as Sinn Fein, have their roots in the violence of the 20th Century when the 1916 Rising led to a guerrilla war against Britain, a civil war and finally an independent Irish state in 1922. With the anniversary has come a resurgence of debate about whether Ireland would eventually have won independence from Britain without revolution.

Historian Professor Diarmaid Ferriter, of University College Dublin, believes this "what if'' fails to take into account the political climate at the time: "Those who were committed to rebellion in 1916 did not feel they were living in a democracy."

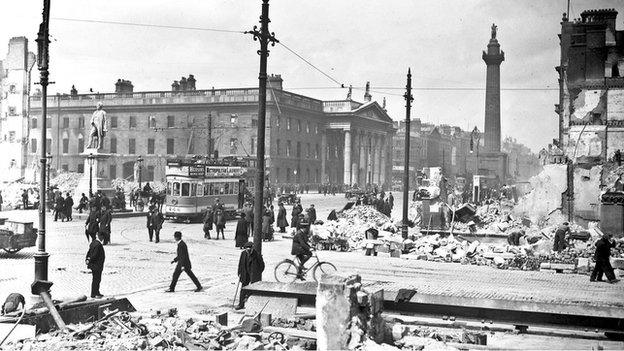

The smoking ruins of one of Dublin's quays

The Ulster unionists were pledging to resist home rule for Ireland by armed force. They formed their own militia and imported weapons and ammunition. The unionists were encouraged by the leader of the Tory party, Andrew Bonar Law, who threatened to support an insurrection against the Crown if home rule was pushed through. This extraordinary declaration of disloyalty did not go unnoticed in the south.

People scrabble amongst the rubble in the streets

The outbreak of war in 1914 also transformed the atmosphere. A looming civil war between unionist and nationalist Ireland was averted. Thousands of men from across the island went to fight against Germany.

The constitutional nationalist leader, John Redmond, whose brother was killed at the Somme, believed supporting the British war effort would help bring about home rule.

But with Britain distracted, the rebels saw an opportunity. "They were very conscious of the might of the British empire and the damage they felt it had done to Ireland," says Professor Ferriter. "They felt justified that this [revolution] would begin the process of Ireland becoming a republic. In the long term they were vindicated in that."

Knockanean school children are studying 1916, and its commonalities with social problems today

Schools across Ireland have been encouraged to commemorate the rebellion with drama, essays and discussion. All of the country's primary schools have written their own version of the Proclamation of an Irish Republic, signed by the rebel leaders in 1916.

I visited Knockanean school in County Clare, external where my great-grandfather Patrick Hassett was a pupil in the 19th Century. His story illustrates the complexity of the Irish relationship with Britain. On leaving school, he became an imperial policeman in the Royal Irish Constabulary.

But his son, my grandfather Paddy, was radicalised by the execution of the 1916 leaders and joined the IRA to fight against Britain.

At Knockanean school the children were being encouraged to look to the future while commemorating the past.

Children at the time of the uprising collect wood

Head teacher Jim Curran spoke of the importance of issues like homelessness and unemployment to the generation of 2016. "We have asked them to remember 1916 but also to think about the country they live in now," he says.

That country will spend the next few days reflecting on the meaning of 1916, before moving on to the business of electing a new government after an inconclusive general election.

Ireland will get on with the patient and often undramatic work of building a state that tries to live up to the promise of the 1916 proclamation, to "cherish all the children of the nation equally".

- Published23 March 2016

- Published23 March 2016