The Middle East is now Europe's backyard

- Published

Belgium was shocked by the attacks, including that at Maelbeek metro station

We are accustomed to thinking about policy in binary terms - domestic politics on the one hand, foreign affairs on the other.

But as the tragic events in Brussels demonstrate once again, home and away are not so easily separated.

Indeed, in a fundamental sense, the problems of a fragmenting Middle East are fast-becoming Europe's problems too.

Whether it be terrorism, the tide of migration, Libya's future, Iran's nuclear policies, or the problematic relationship with Turkey, the wider Middle East is now intruding into the European consciousness on a day-to-day basis.

In some ways, this is a reversion to a long-standing historical norm.

Think back to the colonial era, when France, Italy and Great Britain controlled huge swathes of territory in the Middle East.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the World War One prompted an expansion of the French and British government's responsibilities in the region, with mandates in Syria and Palestine.

More about the attacks

Indeed, the map of the Middle East so much under threat today was largely set by these same European powers after the Great War.

In the past, terrorism too has battered on Europe's doors.

The struggle for Algerian independence in the late-1950s brought terror attacks against French targets.

And a generation later, in the 1990s, Algerian extremists again attacked France, both to highlight their own campaign and to exact revenge against what was seen as the former colonial oppressor.

Shrinking world

But what is happening today seems fundamentally different.

In part, the nature of the Middle East's crisis is more severe.

Many Syrian migrants are attempting to forge a new life in Europe

While geography may be immutable, in tangible ways the proximity of the region to Europe has increased.

And the varied forces of globalisation have at one and the same time increased the attractiveness of the European economic area and highlighted the deficiencies of much of the Arab world.

A globalised culture has served to reduce distance as a factor in world affairs.

European governments are struggling to deal with what first presents itself as a security crisis.

Think of the many European citizens who have travelled to join so-called Islamic State.

Belgium, for whatever reason, seems to be the country that has pro-rata produced the largest number of mobile jihadists.

But think then of the significant, and, in many cases, long-established immigrant communities from North Africa in a country such as France and the infamous anomie of the French suburbs.

Problems of identity, xenophobia and lack of integration produce significant minorities within these communities who may be susceptible to the jihadists' message.

What too of the proven role of prisons in radicalising young rootless individuals?

Once again, in Belgium, these links between alienation, petty crime, and radicalisation are apparent.

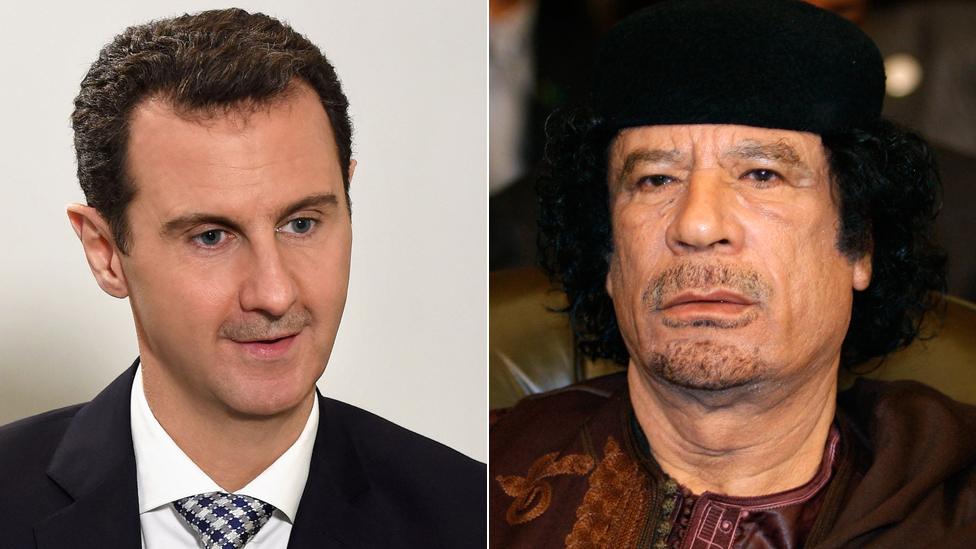

President Assad and Col Gaddafi: One remains in power, the other was deposed

Then add in the question of how to deal with the wider ramifications of the crisis in the Middle East.

At one level, this is a security and foreign policy matter - should the West intervene? If so, how? And to what end?

Decisions were made with regard to Col Muammar Gaddafi in Libya and President Bashar al-Assad in Syria.

One was removed, the other not.

And both these decisions have influenced the current context.

The refugee crisis raises even deeper questions about Europe's values and the nature of the wider society the European Union countries are seeking to establish.

Indeed, problems that in many cases have their roots abroad are now having a significant impact on domestic politics too.

Think of the rise of populist parties in Scandinavia, the strength of the National Front, external in France or the gains made by the far-right at the recent regional elections in Germany.

No certainties

This, in truth, is a problem from hell.

The certainties that informed policy throughout the Cold War and that appeared to triumph at its close are no more.

History didn't end.

It returned to bite the Europeans on the backside.

What governments now face is a Rubik's Cube of problems.

Twist the faces of the cube as much as you like, but you will never align foreign policy, security, immigration, domestic political trends or whatever.

There are just too many moving parts.

And none of the answers is simple.

Security has been stepped up across Europe - including Italy - in the wake of the Brussels attacks

Europeans know they want to be secure.

But they do not know exactly how this state is to be achieved.

How must security be set against privacy?

Should traditional views about freedom of expression be changed in the light of European countries' changing social make-up?

Does military involvement overseas make matters worse?

Or does not intervening simply lead to the mass migration of refugees seeking safety within Europe's borders?

The European Union countries are facing a profound crisis.

The Middle East - just a short distance away across the Mediterranean - is no longer a collection of foreign countries linked to a barely remembered colonial past.

The Middle East should perhaps rightly be described as Europe's "near-abroad".