Migrant crisis: The smugglers' route through Hungary

- Published

Migrants wait in tents on the Serbian border to get into Hungary

Do you see the migrants as victims or criminals, I ask Lt Col Zoltan Boross of the Hungarian police.

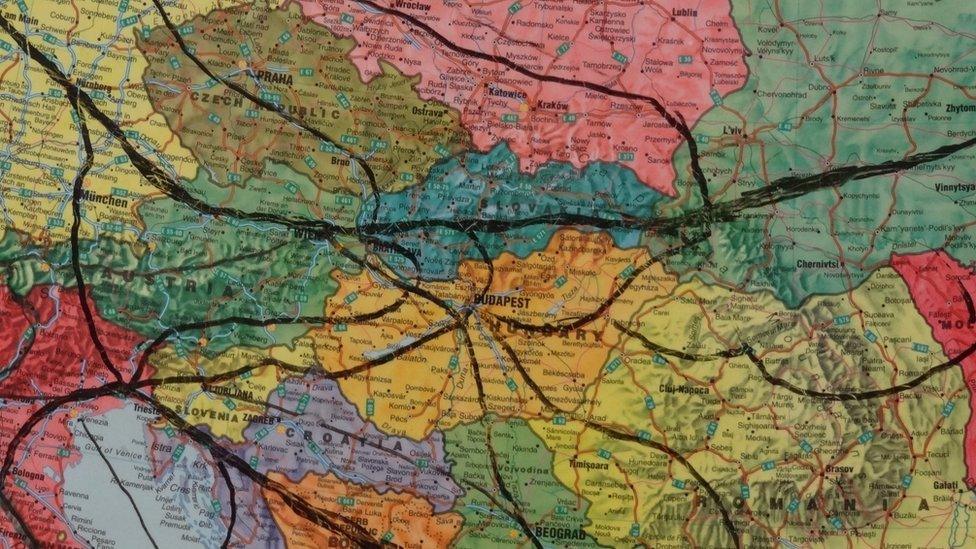

Chief commander in the war against illegal migrants for the past 23 years, he stares over my head at a map of south-eastern Europe scarred by the thick brown arrows which migrants leave on the orderly geography of police forces. "I see them as witnesses against the smugglers," he says.

The migrant route across Hungary has reopened this year, as borders through the Balkans to Austria have become harder to cross.

At least 12,000 migrants have broken through the infamous razor wire fence on Hungary's southern border with Serbia this year.

Most are caught within hours by the army of policemen and soldiers patrolling the Hungarian side.

Some are put on trial for illegal border crossing, but because Serbia is still not accepting deportations from Hungary, most are eventually placed in one of three open camps: at Bicske to the west of the capital Budapest, further west at Vamosszabadi or at Kormend, near the border with Austria.

And there they make contact with the smugglers again, or the smugglers make contact with them.

The police map shows in thick pen the route that migrants are taking to get across the Balkans into Germany

"Unfortunately most tell fairy tales," says Lt Col Boross.

"They think if they give evidence, they won't get help from the smugglers' networks later, to travel on.

"So we look especially for those who have been hurt by smugglers, who have been cheated by them, or hurt in other ways."

There are 110 police officers in six departments dealing with migration at the National Bureau of Investigation. Last year, they put 1,000 human traffickers on trial.

Another 3,500 asylum seekers have been allowed into Hungary through two transit zones built into the fence on the Serbian border, at Roszke and Tompa.

These are mostly women, children, and the elderly. judged as vulnerable by the Hungarian immigration officers working from small booths numbered one to 50 in the transit zones.

They are sent directly to the same camps, without the intervening unpleasantness of detention.

'Message to Brussels'

Down the road from the Biscke camp, in the entrance hall of a Tesco supermarket, Afghan migrants queue at a Western Union money-transfer office.

The bored-looking Hungarian men behind the counter dispense money grudgingly, or sometimes refuse it because of a misspelt name.

"Let's send a message to Brussels, so they understand too!" reads a government poster

Shoppers and security guards eye the scene suspiciously. Two local teenagers try, unsuccessfully, to sell a tablet with a broken screen to the Afghans.

Giant, government-sponsored posters went up all over Hungary this week, calling for a message to be sent to Brussels.

They refer to a September referendum called by Prime Minister Viktor Orban's Fidesz government against what it calls "compulsory quotas" - the relocation of asylum-seekers from Greece and Turkey.

The Budapest government is particularly incensed by the steep "solidarity tax" the European Commission plans to impose on countries that refuse to take refugees allotted to them.

Hungarian immigration officers allow several hundred people a month through the transit zones on the border

Those considered vulnerable are sent directly to three camps in Hungary

On the Serbian side of the border at Roszke, a small camp of tents and makeshift shelters has sprung up.

Most migrants here say they are new arrivals from Turkey who made the hazardous land route across Bulgaria into Serbia, since the border between Greece and Macedonia was closed.

They then carried on north to the Serbian town of Subotica, either by bus or with the help of smugglers.

Elyassin, a 17-year-old Afghan boy, claims he and his companions were beaten by Hungarian police on the Serbian side, before they even reached the fence. Each night, they try to cross again.

Down the road, Said and Fatima, Christians from Iran, say they have no choice but to cross the fence, get caught, then escape from an open camp.

The only option for migrants like Said and Fatima is to break through the Hungarian fence and get caught

They have no chance of getting in legally through the transit zone, because they have no children.

A police car in the dark-green livery of the border police and customs authority cruises slowly through the Tesco car park at Bicske.

A woman in pink tracksuit trousers, who speaks both Hungarian and Farsi, is deep in conversation with a group of Afghans.

At the chief commander's office I ask Lt Col Boross whether Hungary's closed borders are merely pushing more people into the hands of the smugglers.

"The truth lies on both sides," he accepts. "The fence has been effective. But every country tries harder to stop people coming in than going out."

- Published24 May 2016

- Published12 November 2015