Iraq Chilcot inquiry: Bitterness in Baghdad

- Published

What 2003's Iraq invasion did to the country

Almost 24 hours after the massacre of civilians in Baghdad by so-called Islamic State, young men were digging frantically through the basement of one of the shopping centres that was destroyed.

They were looking for human remains. But all they found were some shoes and a pile of black ash. It was hot in the basement. The fire was still smouldering. Warm, scummy water dripped from the ceiling.

Outside, hundreds of people had gathered. Being there was a form of defiance. In the Iraqi capital, any crowded, dark street is a potential target for a suicide bomber.

Perhaps sharing infinite sadness makes it easier to bear. Many people cried, or prayed. I saw a Christian clergyman lighting candles and making the sign of the cross as well as young people chanting a Shia Muslim anthem for the dead.

Just because so many Iraqi civilians have been massacred does not make senseless killing any easier to bear for the survivors.

It is doubtful whether Iraqis who are so caught up in the pain of daily life will take much interest in the long-delayed publication of the UK's official inquiry into its part in the invasion of 2003.

'One thousand Saddams now'

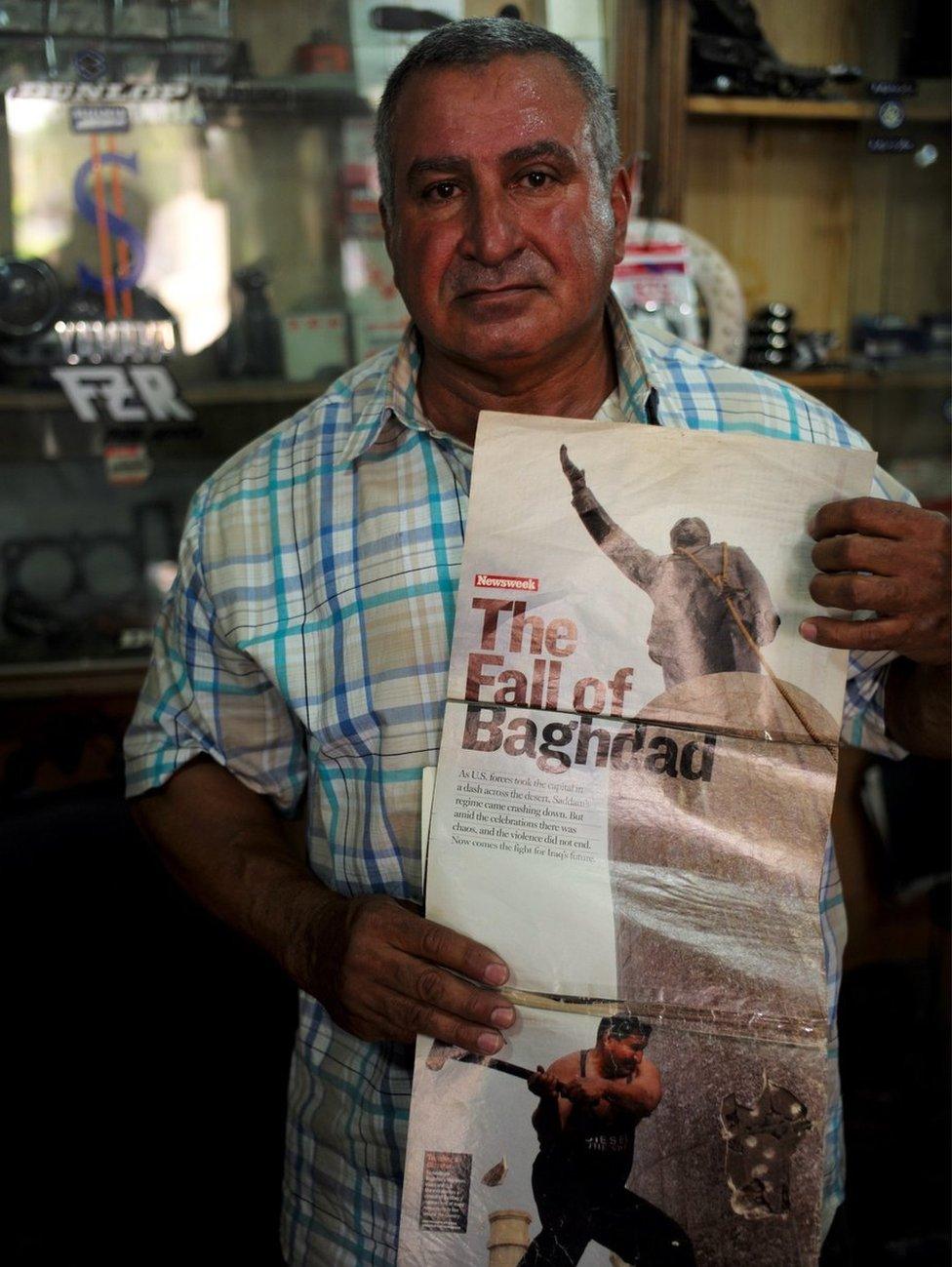

Many people I have spoken to have already made up their minds about the impact of the invasion on Iraq. One of these is Kadhim al-Jabbouri, a man who became a symbol of the Iraqi peoples' rejection and hatred of Saddam Hussein.

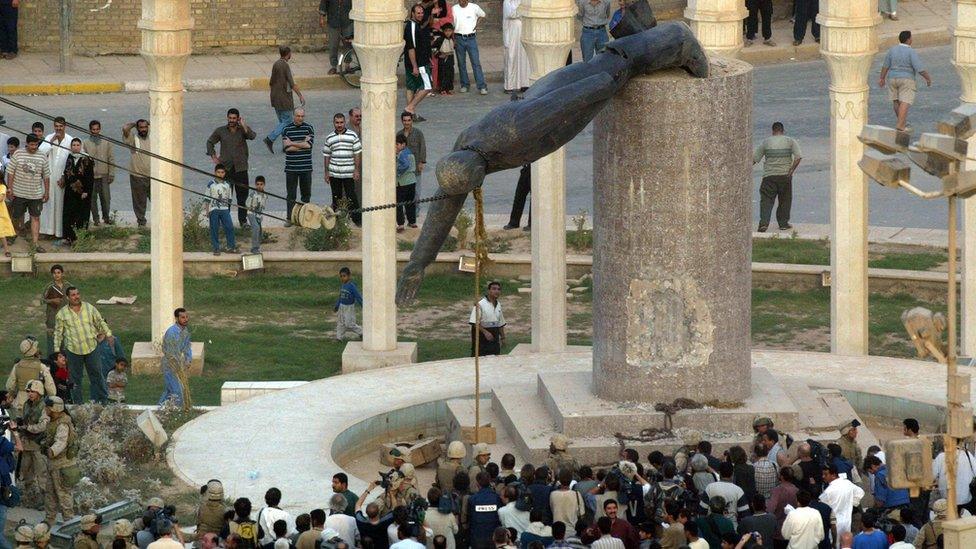

On 9 April 2003, the American spearhead reached central Baghdad. Hours before they arrived, Kadhim, who was a champion weightlifter, decided to bring down the big bronze statue of Saddam Hussein that stood on a plinth in Firdous Square.

Kadhim owned a popular motorcycle shop and was a Harley-Davidson expert. For a while he fixed Saddam's bikes, but after the regime executed 14 members of his family he refused any more work. The regime's response to his effrontery was to put him in jail for two years on trumped-up charges.

This moment, broadcast around the world, was a personal moment of revenge for Kadhim

Kadhim is a survivor. In prison, he started a gym and a weight-lifting club, and was eventually released in one of Saddam's periodic amnesties.

But on the morning of 9 April, Kadhim wanted his own personal moment of liberation and revenge. He took his sledgehammer and began to swing it at the plinth beneath the towering bronze dictator.

Journalists came out of the Palestine Hotel on the square and started broadcasting and taking pictures. Kadhim says their presence protected him from Saddam's secret policemen, who melted away as the sound of American guns came closer.

When the Americans arrived they looped a steel cable round the bronze Saddam's head and used a winch to help Kadhim finish the job. It all happened live on international TV. The image of furious and delighted Iraqis slapping the fallen statue with their shoes went around the world.

Kadhim said his story was told to President George W Bush in the Oval Office. But he now wishes he had left his sledgehammer at home.

Kadhim, like many Iraqis, blames the invaders for starting a chain of events that destroyed the country. He longs for the certainties and stability of Saddam's time.

Kadhim al Jabbouri

First, he says, he realised it was not going to be liberation, but occupation. Then he hated the corruption, mismanagement and violence in the new Iraq. Most of all he despises Iraq's new leaders.

"Saddam has gone, and we have one thousand Saddams now," he says. "It wasn't like this under Saddam. There was a system. There were ways. We didn't like him, but he was better than those people."

"Saddam never executed people without a reason. He was as solid as a wall. There was no corruption or looting, it was safe. You could be safe."

'I'd spit in his face'

Many Iraqis echo that. Saddam's regime was harsh, and it could be murderous. He led the country into a series of disastrous wars and brought crippling international sanctions down on their heads.

But with the benefit of 13 years of hindsight, the world that existed before 9 April 2003 seems to be a calmer, more secure place. They have not had a proper day of peace since the old regime fell.

As for democracy, many I have spoken to believe the hopelessly sectarian political system is broken. At least, they say, law and order existed under Saddam.

Some hoped things might get better after the army's victory over IS in Falluja. The devastating bomb attack in Baghdad in the early hours of Sunday has blasted that hope away.

Inside the hauntingly deserted city recaptured from IS

I asked Kadhim he would do if he could meet Tony Blair.

"I would say to him you are a criminal, and I'd spit in his face."

And what would he say to George Bush?

"I'd say you're criminal too. You killed the children of Iraq. You killed the women and you killed the innocent. I would say the same to Blair. And to the coalition that invaded Iraq. I will say to them you are criminals and you should be brought to justice."

The Baghdad bombing claimed at least 165 lives

A chain of consequences that leads back to the invasion of 2003 caused Iraq's perpetual war.

The Americans and Britain removed a hated dictator, and dissolved his army and state. But they had no real plan to rebuild the country they had broken. They improvised - and made matters worse.

Jihadists were not in Iraq before the invasion. Shia and Sunni Muslims, whose sectarian civil war started during the occupation, could co-exist.

The invaders did not have enough troops to control Iraq. Jihadists poured across open borders. Al-Qaeda established itself here, and eventually was reborn as so-called Islamic State.

Iraqis have often made matters worse for themselves, but it was mistakes by the US and Britain that pushed Iraq down the road to catastrophe.

- Published4 July 2016

- Published4 July 2016

- Published5 July 2016