Iraq Inquiry: What is the Chilcot report and why does it matter?

- Published

The report has taken nearly seven years to complete

The official report into the UK's involvement in the 2003 Iraq War will be published on Wednesday 6 July. But what is it all about and why is it likely to be controversial?

Why is it called the Chilcot report?

A simple one to start off with. The man chairing the Iraq Inquiry is veteran civil servant Sir John Chilcot and so colloquially the report has become associated with his name.

The 77-year old retired from the civil service in 1997, having held a number of top positions, including head of the Northern Ireland Office. The other members of the panel who oversaw the inquiry were academic Lawrence Freedman, ex-diplomat Sir Roderic Lyne and peer Baroness Prashar. The fifth member - historian Sir Martin Gilbert - died in 2015.

When and how will it be published?

Sir John Chilcot will make a statement on 6 July in which he will outline the main findings of the report and the lessons learned. He is not expected to take questions. Once he has finished speaking the full report will be released on the Iraq Inquiry website., external

The report will be published in hard copy in two formats. The full report will consist of 12 volumes and will be 2.6 million words long. Anyone wanting to buy a copy will have to pay £767 and contact The Stationery Office, the private firm which has printed the document. A 150-page executive summary is being published separately. This will cost £30.

Journalists are being given access to the full report on the morning of 6 July and will be able to report what they've read once Sir John finishes speaking.

When and why did Britain go to war?

British troops were part of an international coalition, led by the US, which invaded Iraq in March 2003. The military action led to the collapse of the regime of Saddam Hussein, who had ruled the country since the late 1970s.

The UK's participation was extremely contentious. A total of 179 British service personnel were killed in Iraq between 2003 and 2009, when British troops left Iraqi soil. Tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians died over the period, though estimates vary considerably.

The House of Commons authorised military action 72 hours before it took place but 217 MPs voted against, including 139 Labour MPs. Several members of the then Labour government, including former Foreign Secretary Robin Cook, resigned as a result. The weekend before the vote took place, millions of people took to the streets of London and other British cities to voice their opposition to military action.

Arguments in the run-up to the invasion revolved around whether Iraq possessed chemical and biological weapons, whether it was able to use them and the strength of the intelligence about them.

The invasion was preceded by a long period of diplomacy in which the UK led and failed in efforts to secure explicit United Nations authorisation for military action - a sequence of events which has given rise to a long and heated debate about whether the war was lawful or not, a debate that is likely to continue whatever the inquiry concludes.

What will the report look at?

British troops were stationed on Iraqi soil for more than six years

The report spans almost a decade of policy decisions between 2001 and 2009.

It will cover the background to the decision to go to war, whether troops were properly prepared, how the conflict was conducted and what planning there was for its aftermath, a period in which there was intense sectarian violence.

The report's precise remit, external is to examine what happened and to learn lessons so governments are equipped to respond to "similar situations" in the future.

Why has the report taken so long?

The inquiry was announced by the former prime minister Gordon Brown in June 2009. The assumption, at the time, was that it would take two or three years at most but it soon became apparent it would be much longer.

The first phase was a series of public hearings in which senior politicians, military commanders and diplomats were questioned. This was briefly interrupted by the 2010 general election but came to an end in February 2011.

The subsequent delays which followed have angered the relatives of those killed as well as politicians on all sides of the debate.

The report is a massive undertaking, almost unprecedented in scope, and the inquiry conceded that it underestimated the scale of the task and needed more resources to begin with. There have also been unforeseen events such as Sir Martin Gilbert's death.

But the main reason for the delay was the long tussle between the inquiry and the government over which classified material could be published alongside the report, or referred to in it.

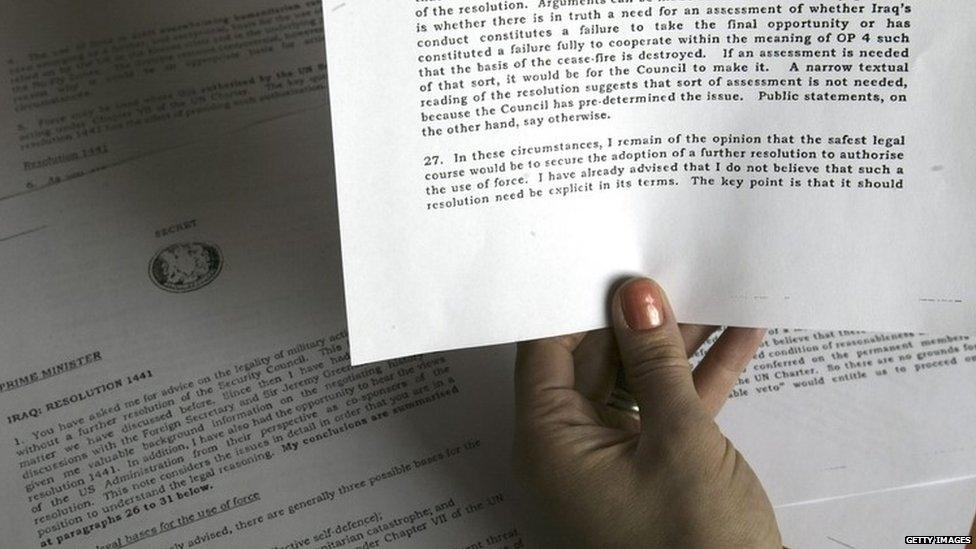

So, what documents will we see?

About 1,500 new documents are expected to be published alongside the report

An agreement was finally reached in the summer of 2014 over access to material such as minutes of Cabinet meetings and the "gists" of personal notes exchanged between Mr Blair and US President George W Bush.

Some of this material would not normally have been released for 30 years so it will give a unique insight into the workings of government and US-UK relations at the time.

Inquiry chairman Sir John says he will not shirk from apportioning blame where he sees fit.

The process of giving witnesses criticised in the report the right to respond - known as Maxwellisation - took longer than expected. It is not clear who was subject to this process, although this may become evident on the day.

The report was pored over by the security services after its completion, with officials reportedly looking for information that may have been inadvertently included which could damage relations with the UK's allies, breach national security or violate the UK's international obligations in any way. However, Sir John said that no material has either been removed or redacted.

Remind me again, who gave evidence?

Tony Blair has insisted that military action was justified

Most of those involved in the decision to go to war have since left front-line politics, although critics say their reputations are very much on the line.

Tony Blair, the British politician most closely associated with the war, appeared twice before the inquiry, defending his decisions and insisting he would do the same again. Gordon Brown, who was chancellor in 2003 and succeeded Mr Blair as prime minister, also gave evidence.

Other senior Labour ministers in the run-up to the war, including former Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon and International Development Secretary Clare Short also appeared.

The inquiry also took evidence from a Foreign Office lawyer who quit in protest at the war, from Lord Goldsmith, the former attorney general who advised ministers that the war was lawful, and UN weapons inspector Hans Blix.

Although witnesses were not asked to testify on oath, all those appearing were asked to sign a piece of paper saying they gave a "full and truthful" account of events.

Will the report affect contemporary politics?

David Cameron and Jeremy Corbyn have opposing views about the 2003 invasion

David Cameron will respond for the government in a Commons debate, in what is likely to be one of his last major parliamentary occasions before he stands down as prime minister in September.

As a backbench MP, Mr Cameron voted in favour of military action and has said he does not regret doing so. However, implementing the report's recommendations, in terms of how government and Whitehall operates, is likely to fall to his successor, whoever that is.

The report, however, will have real significance for Labour and the current turmoil in which it finds itself.

The decision to go to war has cast a long shadow over the party in recent years and is at the heart of arguments over not only Labour's foreign policy and its willingness to contemplate military intervention, but as what kind of party it sees itself.

Its leader Jeremy Corbyn, who was a backbencher at the time, was an implacable opponent of the war while some of those in talks about easing him out, such as Angela Eagle and Tom Watson, voted in favour of military action.

There has been speculation about the degree to which Mr Corbyn will criticise Mr Blair and whether he will go as far as to accuse him of war crimes - a move which would undoubtedly cause further ructions in the party.

This is not the first inquiry into Iraq, is it?

No. There have already been four separate inquiries into aspects of the Iraq conflict. In 2003, the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee and the joint Parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee both looked into the intelligence used to justify the war.

The Hutton inquiry, in January 2004, examined the circumstances surrounding the death of scientist and weapons adviser Dr David Kelly. The Butler inquiry, in July 2004, looked once again at the intelligence which was used to justify the war.

- Published4 July 2016

- Published7 July 2016

- Published9 May 2016

- Published29 October 2015

- Published5 July 2016

- Published29 October 2015

- Published29 October 2015