Turkey failed coup: Who are the Gulenists?

- Published

Legitimate clampdown or purge too far? Mark Lowen investigates

A small, handwritten note flutters on the gates of a school in Istanbul's Sisli district.

"Within the context of the state of emergency, this education institution has been closed and its property has been given over to the treasury," it reads.

Above the signature is the red seal of a notary. Run by or close to the Islamic preacher Fethullah Gulen, it is one of the almost 1700 schools closed down in the past fortnight, now labelled a breeding ground for terrorism.

From education to the military, judiciary to NGOs, police to private businesses, the post-coup purge has been staggering.

Among the media, 131 outlets will be closed. In the military, 1,700 officers have been discharged, including almost half of Turkey's admirals and generals.

Nearly 16,000 people have been detained. Even some 250 cabin crew at Turkish Airlines have been dismissed: all suspected backers of the coup or of Fethullah Gulen.

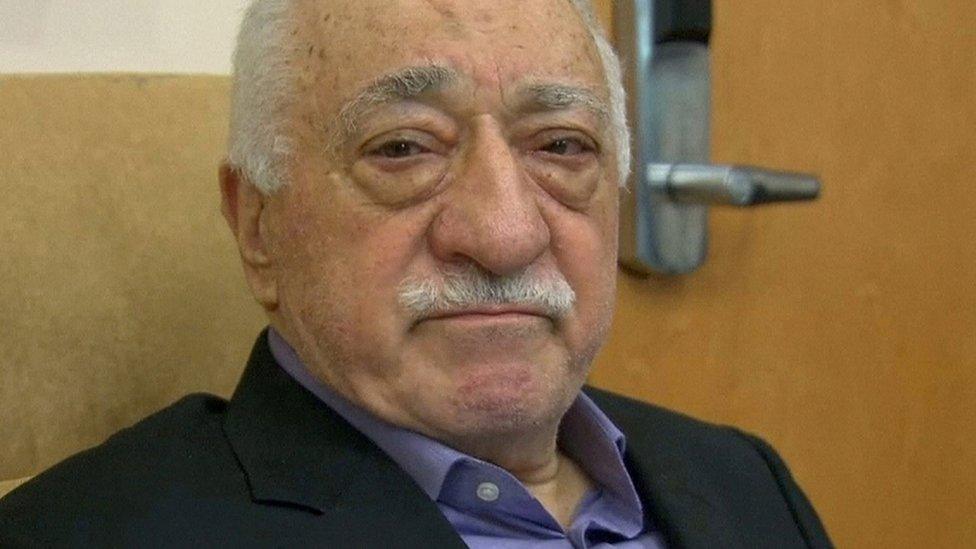

Mr Gulen and his supporters have been blamed for the failed coup earlier in July

The scale of the clampdown has drawn criticism from Western governments.

But to grasp what is happening requires an understanding of the Gulen movement: a man whose followers have spread through Turkey's institutions for the past four decades.

Fethullah Gulen emerged in the 1960s as an Islamic preacher within a constitutionally secular Turkey.

His advocates call him a guru of moderate Islam tinged with humanitarianism, delivering his ideology through a network of high-achieving schools in Turkey and about 140 countries.

Critics say he has built a dangerous cult that has infiltrated all corners of the Turkish state - a fifth column that has shown its true colours in this latest coup attempt.

Members of his movement were embedded until recently within virtually every institution.

More on Turkey's coup

A leaked diplomatic cable from the US ambassador to Turkey in 2009 read: "The assertion that the [National Police] is controlled by Gulenists is impossible to confirm but we have found no one who disputes it."

A grainy video of the cleric emerged in 1999 apparently calling on his followers to "move within the arteries of the system, without anyone noticing your existence, until you reach all the power centres… You must wait until such time as you have got all the state power".

Mr Gulen, who has lived in self-imposed exile in the US since 1999, says his words were manipulated.

Some of those who have reported on the shadowy network over the years have faced lawsuits, such as the journalist Ismail Saymaz.

"The Gulen structure aims to surround the state from within and take over", he tells me.

"They're not armed militants but cloak themselves as judges, teachers, police, MPs and businessmen.

Journalist Ismail Saymaz says the Gulen network aims to "take over" the state

"Right-wing governments have used the Gulenists against the secular military - the movement got its biggest power during Recep Tayyip Erdogan's rule."

The Erdogan-Gulen alliance was indeed strong: an Islamist pair reshaping a once fiercely secular Turkey.

But as Mr Erdogan's conservative AK Party became entrenched in power, rivalry grew.

When a series of leaked phone calls in 2013 appeared to implicate Mr Erdogan and his inner circle in corruption, the Gulenists were blamed.

They were painted as a "parallel state", who had also struck years earlier, when the movement was widely believed to have fabricated evidence in the so-called "Ergenekon" and "Sledgehammer" cases: two sham trials accusing hundreds of military officers of plotting a coup.

The convictions were eventually overturned.

Naval captain Ali Yasin Turker was among those sentenced during Sledgehammer.

This navy captain blames the Gulen network for his wrongful conviction

He spent 33 months in prison before the conviction was crushed.

"The media close to Fethullah Gulen carried out an operation against us, violating our right to a free trial", he says.

"His followers were in the police and judiciary but they didn't have enough in the military so they were trying to replace us with their own."

So did the military purge during Ergenekon and Sledgehammer pave the way for this latest coup?

"Certainly. If they hadn't been able to get rid of us then and put their own followers in the military, they wouldn't have been able even to think about a coup, let alone carry it out."

Many of the so-called Gulenists left Turkey in recent days or weeks, fearful that they would be arrested.

We tracked down Abdullah Bozkurt, a former journalist from Zaman, once Turkey's most-read newspaper and the biggest Gulen media outlet.

Mr Gulen himself lives in exile in the US

He moved abroad this week and denounces a "witch-hunt targeting every critical, dissenting and opposition journalist - whether thought to be affiliated with Gulen or not".

"How could you plot a coup through a media organisation?" he asks.

"This is collective punishment without any evidence. The government is simply killing alternative narratives and intimidating people not to ask serious questions."

I ask what it means to be a follower of Gulen.

"It's an intercultural, interfaith dialogue. I don't believe this is the infiltration of Turkey. Where do you expect students from his schools and universities to go? They needed to find jobs in the public and private sector."

And what of allegations that the movement is a sect, a sort of Turkish Opus Dei?

For Turkish government supporters, Mr Gulen is a hated figure - this sign calls him a "traitor"

"I don't believe in that nonsense", he says.

"You hear all sorts of rhetoric from the government blaming the Vatican or America or other conspiracy theories. They have a track record of shifting responsibility. The Gulen movement is a perfect scapegoat."

Opposition to the attempted coup has united Turks - but punishment or purge is uprooting almost every part of society.

President Erdogan appears vindicated in his constant talk over the years of an "enemy within". But criticism still continues that the clampdown is going too far.

The Turkish government is demanding Fethullah Gulen's extradition from the US - but Washington says it's still waiting for evidence that he's involved.

He and his supporters say there is none, insisting they are a peaceful interfaith movement.

But the attempted coup has largely turned Turkish society against them and the calls are loud to flush out the Gulen influence once and for all.

- Published16 July 2016

- Published17 July 2016

- Published18 July 2016

- Published16 July 2016

- Published15 July 2016