Go-getters in the ghettos: The bright side of France's migrant suburbs

- Published

The banlieues made the news during riots, as in 2005, but there is another side to them

Like many French rap stars, Mokobe has drawn inspiration from growing up in one of the bleak "banlieues" (suburbs) where immigrants make up a large part of the population.

One of 15 children of West African parents, he remembers bunk beds gradually filling up the bedroom until the window could no longer be opened. New arrivals then had to sleep in the living room of their flat on the south-eastern fringes of Paris.

"We used to tell each other stories at night," the 40-year-old recalls. "I've always liked living in a housing estate because we're on top of each other. Mixing and sharing are part of life there."

Mokobe, who has filled venues from Chad to California over a two-decade career, believes his banlieue roots have given him an edge as a performer.

This picture belies the image of the ethnic hinterland of French cities as ghettos. The country often stands accused of failing to integrate migrants, leaving them to fester in crime-ridden poverty.

Up from the banlieue

Marginalisation is often blamed for regular waves of rioting and for the rise of home-grown jihadists, such as those who struck Paris last year and Nice in July.

After the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January 2015, the French prime minister denounced "geographic, social and ethnic apartheid".

But, wretched as they undoubtedly are, the banlieues are in reality hotbeds of upward mobility.

Mokobe sees bright side of suburbs

Entertainers like Mokobe and sports stars are not the only people to arise from the banlieue and thrive. Most of the rapper's childhood friends, he says, have moved on to have successful careers.

French rapper Mokobe: "I've always liked living in a housing estate"

Research shows that far from being ghettos, "Sensitive Urban Zones" in official parlance (ZUS) - are the parts of France that have the highest population turnover.

Two-thirds of those who lived there 10 years ago have left and been replaced by newcomers, typically other migrant families, says Christophe Guilluy, a geographer.

It is true that the ZUS score poorly on every economic indicator. Unemployment there is two to three times the national figure. Crime is rampant.

But this disturbing social picture is not inconsistent with individual success. "The jobless banlieue-dwellers of today are not the same as yesterday's and will not be the same tomorrow," as Mr Guilluy puts it.

For most residents, ZUS are transit zones. If they were traps, they would be full of pensioners. "Outside the tower blocks you would see men playing cards, just like in villages," Mr Guilluy says.

But what first strikes you in any banlieue is how young people are.

Those people who rioted in 1990 are now pushing 50 and have moved on. "It is not them who throw stones at police cars today," Mr Guilluy says. "This shows the very real economic integration of people who have left the banlieues."

Gritty

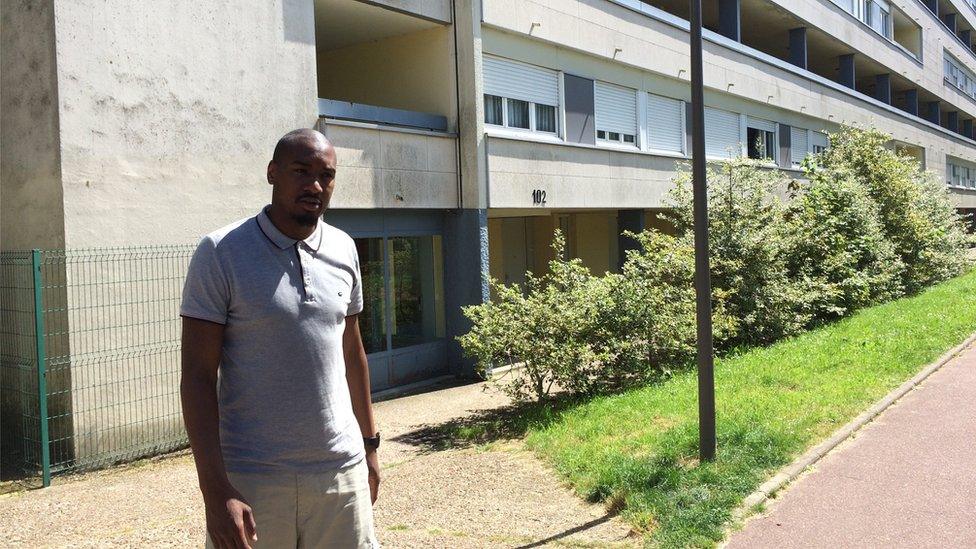

Moussa Camara has worked to channel the youthful energy of immigrant areas for almost a decade.

In 2007, as a budding entrepreneur from a rough estate in Cergy-Pontoise, west of Paris, he decided to take action after police shot and wounded a local boy while chasing joy riders. Memories of nationwide banlieue riots 18 months earlier were still fresh and tensions high.

Moussa Camara is seeking to unleash entrepreneurial potential of the banlieues

Mr Camara convinced people that lobbying was the most effective form of protest and got them involved in local politics. He later connected jobless youths with local firms. Now - with support from the main employers' federation - the 30-year-old helps them start their own companies.

The entrepreneurial spirit, he says, is hungrier in the banlieues than anywhere else.

"When you live in a neighbourhood with so many social problems and your only to chance is to start a business, the grit and determination are not the same," he says. "Here, when you give kids a chance, they give it all they've got."

Sharron Manikon: 'I'm proud to come from Aubervilliers'

"When people say to me you come from Aubervilliers, I say yes I do but then I went to London and then I came back from London I integrated a business school. I'm proud and I always make sure people know I come from Aubervilliers."

Sharron Manikon, 34, entrepreneur, born and raised in Aubervilliers, north-west of Paris

Having a point to prove is a big motivation for many migrants' children. Sandra Meknassi, whose grandparents came from North Africa, grew up on a council estate in Goussainville, north of Paris.

At school her form tutor once told her, in front of the whole class, that she should forget about studying law.

The 25-year-old now works as a junior lawyer for a multinational insurance group. "My dream," she asserts, "is to return to my old school and say to that form tutor: 'So there.'"

Banlieue schools, despite their dire image, by and large fulfil their role. The proportion of those who take the baccalaureat and succeed is only 5-8% lower in ZUS than elsewhere.

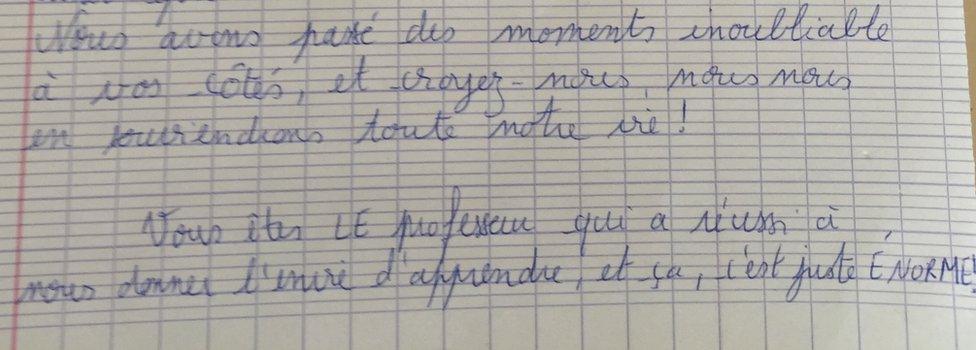

Iannis Roder, who has taught history to mostly immigrant children in the same school near Paris for 18 years, says that receiving effusive letters of thanks from former pupils who are now in higher education is what keeps him going. "It brings tears to my eyes," he says.

Former pupils of Mr Roder say they will remember him forever

Education, of course, is not an automatic ticket out of the banlieue. For every tenacious Sandra, many will fail to reach their potential.

Some remain in the banlieue through sheer bad luck. Cinthia Piquionne and her family are stuck in the estate Sandra left behind. At 46, she is too old to get a mortgage.

"I would have liked to have a house with a garden," she sighs. "Sometimes you have to give up on your dreams."

Cinthia Piquionne would like to move to a more salubrious neighbourhood but she cannot

Discrimination remains a disturbing fact. Sociologist Emmanuelle Santelli has studied an entire cohort of schoolchildren from a ZUS near Lyon, and followed them into adulthood.

By their late 20s, half had moved out of the area. Three-quarters were in work, many in stable employment, but the majority had insecure jobs that did not match their skills. Crucially, those of foreign origin fared worse than those with French roots.

There is social mobility in the sense that migrants' children do better than their parents, Ms Santelli says.

"But they must not be compared just with their parents or grandparents," she adds. "They must above all be compared with other French people of the same age." In that respect they are at a disadvantage.

The Ariane housing estate in Nice is predominantly Muslim

Some believe that marginalisation is partly self-inflicted. Boubekeur Bekri, a moderate imam from a part of Nice bristling with satellite dishes and Islamic fervour, believes Muslim culture itself is holding people back.

Banlieue students are given plenty of opportunities and many grab them, he says, but the prevalent mindset does not encourage them to do so.

"High-achievers here are made to feel they are letting the side down," says Mr Bekri, who is also a teacher. "Top students have a difficult time. Their success is seen as an insult to the neighbours."

Quiet rise

Whatever the reason, banlieue immigrants are under-represented among the better off. But, for Christophe Guilluy, this does not mean that social integration is failing.

French suburbs, he says, are going through the same process that has seen paupers flock to slums in hope of a better life all over the world.

Rags-to-riches stories are rare. The norm is what Mr Guilluy calls "invisible social ascent" - families gradually, quietly improving their lot.

One sign of this unsung development is the emergence all over France of multi-ethnic residential areas accommodating a rising class of immigrant households.

One of these, Maurepas, was once a sleepy town south-west of Paris. Over the past two decades it has seen an influx of families escaping the dismal estates of Trappes just up the road.

Marie Monroy, who teaches literature at a school in Maurepas, experiences French-style integration in her classroom every day.

The third of her pupils who have foreign roots perform no differently from the others, she says: "Some children are unwilling or unable to learn, but it has absolutely nothing to do with their origins."

Abdelghani Merah (right) is fighting the deadly legacy of his little brother Mohamed

If French banlieues were on trial for breeding only despair and jihadism, Abdelghani Merah would be a star witness for the defence.

He is the brother of Mohamed Merah, France's first home-grown jihadist.

They grew up in the same sink estates in Toulouse but followed very different paths. Mohamed nurtured a grudge against France and vowed to fight "infidels"; he killed Jewish schoolchildren and soldiers during a shooting spree in 2012.

Abdelghani married a woman of Jewish origin. The 39-year-old now goes around housing estates in the Nice area to extol "beautiful" French values. The anti-immigration National Front, he says, "is not what France is about".

Mohamed died childless in a hail of police bullets at the age of 23.

Abdelghani has a 20-year-old son who is attending a top business school.

- Published24 August 2016

- Published24 August 2016