The women of France's banlieues

- Published

Svetlana: " When I see kids hanging around on their quad-bikes, I think: I don't want my children to be like that."

The deprived suburbs of French cities, home to many migrants, suffer from high unemployment, alarming crime rates and all sorts of social disadvantages.

But there is a hopeful side to the "banlieues".

They have a higher population turnover than other parts of France. Most residents - though by no means all - leave within a few years, and are upwardly mobile.

Here women from the banlieues speak about their lives and hopes for the future.

Cinthia Piquionne, 46, catering worker, and her daughter Svetlana, 20, student

Cinthia has lived all her life in Goussainville, on the north-eastern fringes of the Paris area. Her parents settled there from the French West Indies in the 1960s.

Cinthia and her family rent a flat in the housing estate where she grew up. The place, she says, has changed a lot since then, and "not always for the better".

Cinthia Piquionne would like to move to a more salubrious neighbourhood but she cannot

There has been an influx of migrant workers over the past 20 years, in part because of good transport links - Goussainville is on the regional rail network and central Paris is just 25 minutes away by train.

The town now has sizable communities not just from sub-Saharan countries and North Africa, but also from the Middle East, Turkey, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

As foreigners moved in in higher numbers, locals moved out. "There are fewer and fewer people of French origin in Goussainville," Cinthia says.

She is not interested in relocating to the remote periphery of Paris, as many French people have done. Goussainville is a short drive away from Charles de Gaulle airport where she works for a company making airline meals.

Still, she would like to leave her estate. "People here do not respect the place," she says. As an example, she mentions a recycling scheme that did not last: people just left their rubbish on the pavement.

Cinthia would like to move to a more salubrious part of Goussainville

A few years ago Cinthia and her family tried to move to a nearby residential area, but could not as her husband was unemployed. Now both have jobs but properties in Goussainville have become too expensive. At 46, she can no longer afford a mortgage.

"I have four children and must choose my priorities. I would have liked a house with a garden," she says. "Sometimes you have to give up on your dreams."

The best Cinthia's family could do was get a new apartment in a slightly quieter corner of the estate.

Svetlana, Cinthia's 20-year-old daughter, has a better chance of doing moving out.

Walking through the estate, she points to a spot near her old flat where kids used to set rubbish bins alight. "We see a lot of burnt cars over there," she says. "There have been fights as well."

Over there is a good spot to set rubbish bins alight, Svetlana says

Svetlana's future is uncertain - she talks about becoming either a philosophy teacher or an interior designer - but she is sure she wants to leave Goussainville behind.

What worries her is that youths on the estate "do not have any goal in life".

"I feel a bit lost myself. I'm not sure what I'm going to do with my life," she says. "When I see kids being so aimless, hanging around all day on their quad bikes, I think: I don't want my children to be like that."

Sharron Manikon, 33, entrepreneur

The daughter of migrants from Mauritius, Sharron grew up in Aubervilliers, a northern suburb of Paris with a rotten reputation. As a teenager, she struggled to get part-time jobs because of where she lived.

But she did not give up. Sharron went off to study at London Metropolitan University, returned to Paris to cut her teeth as a businesswoman and get an MBA while raising a family.

With years of experience in the tech sector under her belt, she is launching a digital strategy consultancy.

Sharron Manikon: 'I'm proud to come from Aubervilliers'

Coming from Aubervilliers, she says, has toughened her for life as an entrepreneur. "Every time someone tells me I can't do this, I tell myself I will prove them wrong."

"I always say to young people: if you don't say what's on your mind, no one is going to know. You have to move, you have to do something. I had a lot of support from my family and my friends but I always knew it was down to me."

Sharron's hometown was once a burden, but now she regards it as a badge of honour.

"When people say to me you come from Aubervilliers, I say, yes I do but then I went to London and then I came back," she says. "I'm proud and I always make sure people know I come from Aubervilliers."

Imene Ouissi, 22, student

Imene lives with her Tunisian mother and her brothers on a council estate in Vallauris, near Nice.

Until she was 15, she attended a local school where most pupils were of North-African origin, like her.

Imene Ouissi: "We'd like to live in a quieter area, with less fear."

The teachers' expectations, she says, were minimal and so was the teaching. In literature, instead of the classics, they were given modern stories about immigrant families to read.

A teacher once told her she would end up working as a housemaid. "That kind of insult left us traumatised," says Imene. Most of her friends dropped out at the age of 16.

Thankfully, another teacher saw her potential and fought to get her a place in a lycee, where she could prepare for the baccalaureat.

Imene discovered with wonder that there was more to French literature than tales of growing up on high-rise estates.

She worked hard to catch up in her studies and passed her "bac". She is now studying to become a social worker while volunteering for a women's charity in Vallauris.

Ideally, Imene would like to get a master's, but she is settling for a lesser degree as she needs to start earning enough money to help her family move out of their estate.

"We'd like to live in a quieter area, with less fear," she says. "I worry about my younger brothers. It's tough here. And there is still discrimination in education. I'd like to take them to another school where they'll be properly looked after."

Sandra Meknassi, 25, trainee lawyer

Sandra is the granddaughter of North African migrants. Her father is a taxi driver and mother a municipal employee. Both were born in France.

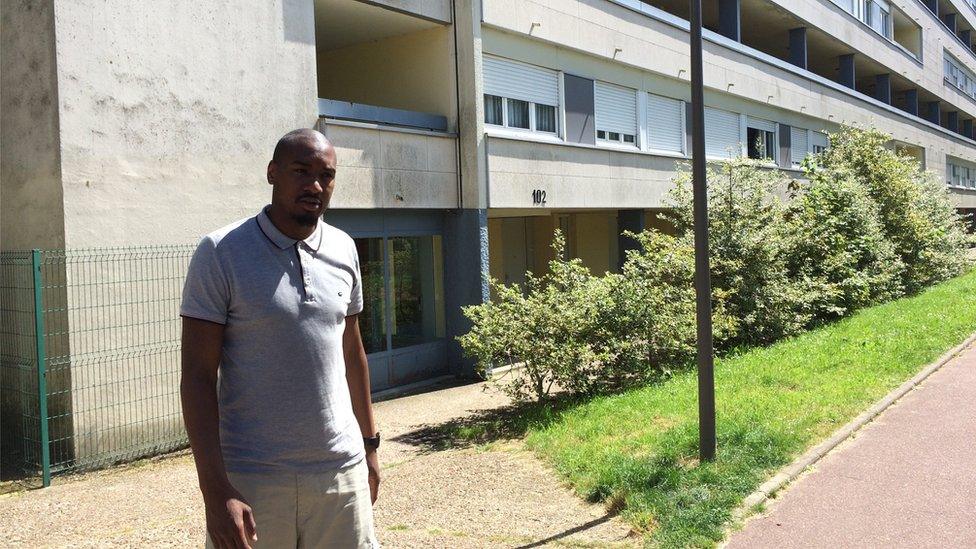

Sandra grew up in the Goussainville estate where Cinthia Piquionne and her family still live. But unlike them, her parents were able to move to a nearby residential area when she was 14.

Goussainville has good rail links... and tight security

However she stayed in the same school, and has no serious complaint with the education she received.

She was once humiliated by a form tutor who ridiculed her aspiration to study law. "Look at her!" The teacher said in front of the whole class, "She has ideas above her station."

But other teachers, Sandra says, encouraged pupils to go for good careers. "They told us that if we tried, we would at least have the satisfaction of giving it a good shot."

She got her degrees with flying colours, and now works a trainee lawyer for a multinational insurance company.

At no point did she feel discriminated against. Her North African background, she says, "was just never a factor".

She denies being exceptional. Many of her old school friends, she insists, are in business schools.

Although Sandra's professional ambitions have materialised, one personal wish may not. "My dream is to return to my old school and say to that form tutor: 'So there.'"

- Published24 August 2016

- Published24 August 2016