French rapper Mokobe cherishes banlieue roots

- Published

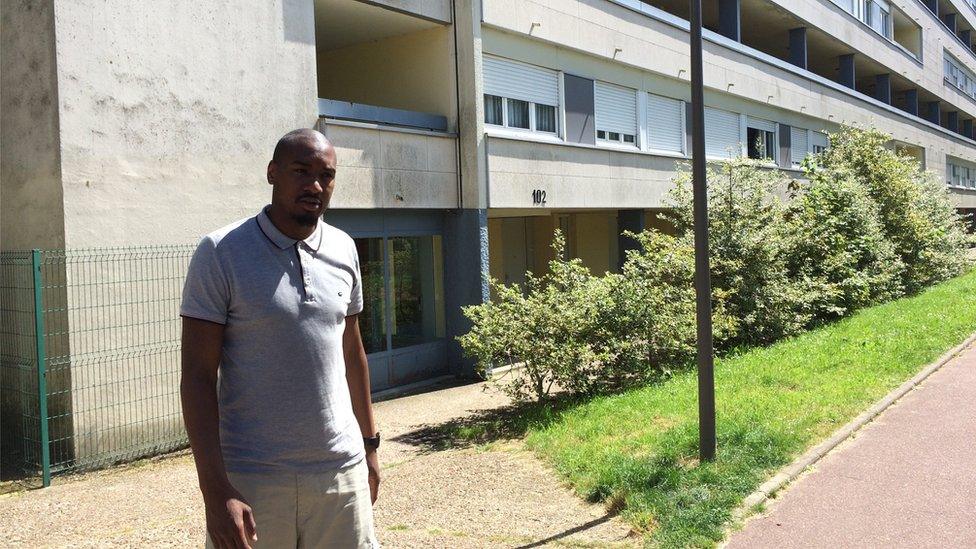

French rapper Mokobe: "I've always liked living in a housing estate"

French Rapper Mokobe has filled venues from Dunkirk to Dakar, but he has never forgotten his roots in the banlieue - the multi-ethnic hinterland of France's cities.

On the day he agreed to meet us in a shisha bar in Paris, Mokobe comes late. He has gone to support families in Montreuil, an eastern suburb of the capital where reports of paedophilia at a pre-school have caused alarm among African migrants.

Moboke uses his celebrity status to raise awareness of issues that are often overlooked. "It's silly to denounce injustice from a studio without talking to people," he says.

The 40-year-old calls himself "100% banlieue".

One of 15 children of a Malian-Mauritanian mother and Malian-Senegalese father, he was born as Mokobe Traore on a housing estate in Vitry-sur-Seine, south-east of Paris.

Small world

His fond memories of growing up there belie the common image of the banlieues as a high-rise wasteland.

"At first there were four of us in two bunk-beds in the bedroom," he says. "Then we were five, then six. That meant we could no longer shut the window." When more children came they had to sleep in the living room.

"We used to tell each other stories at night," Mokobe recalls. "We had very little but learned to share and were happy," he says. "You get certain principles and certain values from living in that estate."

Some of the estates where Mokobe used to hang out as a teenager have been pulled down

Mokobe has not always highlighted the bright side of living in a banlieue.

When he burst onto the rap scene in the 1990s, as part of the hip-hop trio 113, he expressed the frustration aspects of life there: "We were rebels. We made music to speak about our daily lives, about people like us, and to defend their cause."

The main problem with immigrant suburbs, he says, is a feeling of marginalisation. "Isolation can be stifling and lead to eruption. It's like a volcano full of lava. It gets very hot."

His lyrics have become less angry with age. As success led tours in France and abroad, the sense of being confined faded, and Mokobe's main themes became inclusiveness and openness to the world.

Mokobe's first solo album, Mon Afrique (My Africa) released in 2007, explored the complex, but ultimately enriching, cultural heritage of French children of African parents.

The main message behind his forthcoming album, On Est Ensemble (We Are Together), is all in the title, he says: "Regardless of your origins, your culture, your social class, whatever happens, we all live on the same planet. We don't have a choice."

Language barrier

This simple idea, Mokobe believes, has been undermined by social media. Nowadays people are all too aware of faraway events that divide us, he says.

He contrasts this with the small world of his old housing estate, where isolation had at least the virtue of breeding togetherness. "Blacks, Arabs, Chinese - we were all in it together," he says.

Brotherhood is one of the values the rapper promotes on his regular visits to banlieues. In schools also lectures children on the need to pay attention in class - particularly in English lessons which he himself neglected as a boy.

Even after travelling 20 times to the US over the years and playing in San Francisco, New York and many places in between, he says he is "hopeless" at English.

"When I performed at the BET [Black Entertainment Television] Awards in Los Angeles in 2011 I was completely lost," he smiles.

But his main message to banlieue children is one of hope: "It's important not to give up, and to have faith in the future. Childhood friends of mine have become lawyers and doctors. Living in a housing estate does not seal your fate."

- Published24 August 2016

- Published24 August 2016