Italy's constitutional conundrum

- Published

The Italian political system is a joke. Quite absurd. Not my judgement but that of the Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, external.

Laws are made at a snail's pace and there have been 63 governments since the war, many lasting just a few months. That's why he's called a referendum, external to streamline the whole system, and give more power, to, yes, you've guessed it, the prime minister.

But it is a referendum which could claim his scalp. When he first called for the vote he made it clear he'd resign if he lost. With the result in the balance, and the example of Mr Cameron before him, he's tried to back-pedal. In a recent speech, external he said if Italy votes No it "wouldn't mean the end of the world, there would be no plague of locusts."

Privately he's said he exaggerated the impact of defeat but he knows exactly what he would do if he's defeated - but adds there's no point in him repeating it.

The shine is coming off Italy's youngish, reforming, charismatic and energetic prime minister. If he goes, it matters, of course, for Mr Renzi and his country. But it has much wider implications. He, along with the German chancellor and French president, are managing the terms of Brexit, external.

Moreover, his ejection from office could put Italy on a course that would cause yet more instability for a European Union already very nervous about its own future.

Chancellor Merkel, President Hollande and Prime Minister Renzi are at the forefront of the EU's post-Brexit discussions

In Renzi's old powerbase, Florence, they're trying to rally the troops with nightly parties in the park. With the backdrop of blaring music and a funfair, stalls are covered in the patriotic red, green and white bunting of Renzi's Democratic Party, selling pasta and pizza to raise funds.

One woman tells me she will vote Yes but Renzi is unpopular - people have no hope any more.

Signs proclaim "Italy says yes - for efficiency and stability." But that is by no means certain. A guy selling his rather excellent craft beer tells me that he needs to find out more about the referendum - he doesn't really know what it is about.

A lot of Italians are in the same boat.

Some opinion polls, most of which give a narrow lead to No indicate that 50 to 60% of voters haven't made up their mind or don't know what the referendum is about.

Renzi's plan to streamline the iconically chaotic Italian political system centres on the Senate, external.

At the moment the two houses of the Italian Parliament are just about equal. He would emasculate the Senate, strip it of its power, cutting membership from 300 to 100, and stopping direct elections.

The Italian referendum focuses on plans to reduce the powers of the country's Senate

Instead regions would indirectly elect politicians who are already mayors or councillors. The right to hold a vote of confidence in the government would be scrapped, as would the "navette" or "little bus" system, which sees legislation trundling from one house to the other, until the wording is exactly agreed.

Separate from the referendum proposal, the Italian equivalent of the House of Commons would change, external to something much closer to one elected by a "first past the post" system. Whoever got over 40% would automatically get a majority. If no one did, the top two parties would have a contest and the winner would get the majority. It would concentrate power in the hands of the prime minister, so it is pretty important.

But guess what? That may not be what people vote about. At a meeting I was at recently an Italian politician quoted Winston Churchill on referendums - "people vote not on the question, but on the people who ask the question." I'm not sure the quote is accurate, but the sentiment certainly is.

Take Roberta Gianni. She lost all her savings, 60,000 euros, in a banking collapse last year, and blames Renzi.

She tells me "we don't need such a figure. We need someone who is very close to the people and he's not. He's close to financial power." She will be voting No.

Italy is the main entry point for migrants from the Middle East and North Africa

She won't be alone - Italy has plenty of discontented voters. The banking crisis isn't over yet, external, Italy's unemployment is high, external and growth remains sluggish, external. The country is the main point of entry for migrants from across the Med. The prime minister's once sky-high popularity is dropping.

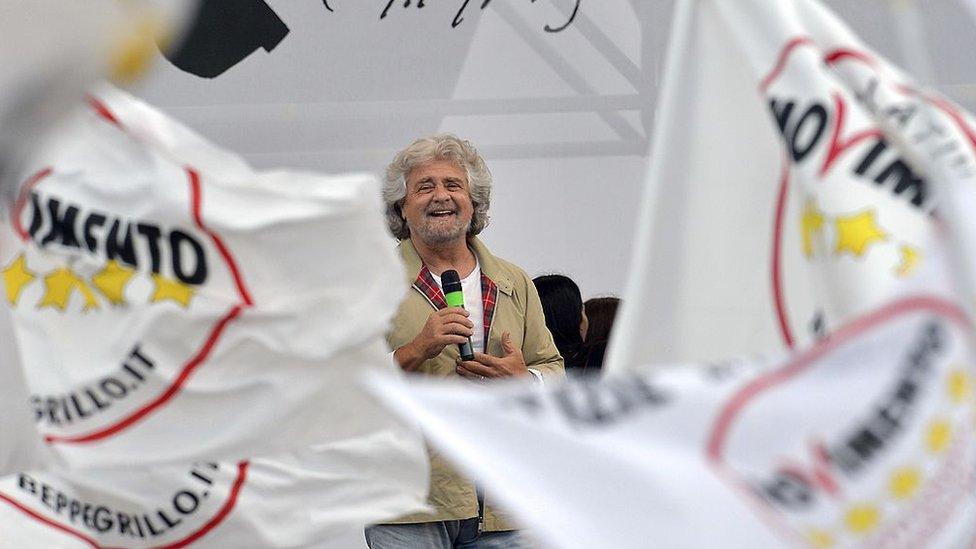

Italy could be the next country to seriously question its relationship with the EU. Growing in popularity, big in the No camp is the Five Star movement, external: anti-establishment, populist, wants Italy to be governed by referendums, not what it sees as an elected old elite. The next referendum, they say, should be on whether Italy should leave the euro.

In 2008 , just before Five Star was born, I interviewed its founder, stand up comedian, Beppe Grillo. He organised "F... Off Day" and told me "We are enraged, we have a feeling of hopelessness."

That has only grown in the eight years that have passed. One newly elected Milan councillor I speak to, Simone Sollazzo, says the movement's members are inspired by Brexit.

The Five Star movement, led by comedian and politician Beppe Grillo, is a major force in the No campaign

"I am for No - absolutely and completely No - to defend the Italian constitution," he explains. "We want direct democracy, not representative democracy, and I am looking at Britain as a certain style we could copy."

Among all the populist movements that have sprung up over Europe and the United States, Five Star is perhaps the most fascinating and perplexing. It is neither left nor right, but draws inspiration from both, incoherent in policy, consistent in rage against those in power.

Its view of the European elite is that Italy, along with other countries in the South, has been painfully slow at introducing the labour market and structural reforms necessary to make the economy more dynamic.

But Italy is a complex conundrum within a cliché. In all its tottering from one emergency to another, for all its much-derided economic weakness, the idea of the dolce vita remains strong.

Perhaps a trite observation, but the resistance of Southern Europe to certain demands of the market is not trivial. Movements like Five Star reject that neo liberal imperative, as much out of instinct as through any alternative policy.

Italy is a particularly important case - it has long resisted economic efficiency, clinging to almost pre-capitalist, pre-modern relationships, networks of family and friendship - to some the essence of corruption. But some supporters of movements like Five Star might see in this the seeds of something distinctly post-modern.

Former prime minister Mario Monti says the referendum should not be seen as a life-or-death issue

Those questions will remain. The fate of Matteo Renzi will be sealed by the end of November (there is as yet, no date, for the referendum).

There are those who think his simple mistake was making it all about him - particularly dangerous for a PM who, like Mrs May, came to power as the result of party strife, not via a general election.

The former Italian prime minister Mario Monti tells me: "I am in favour of some of these changes but I am against making it a matter of life or death for Italian economic performance or democracy."

He thinks Yes will win, and if it doesn't the PM will stay. If he doesn't the system is stronger than one man. In fact many think that if Renzi is forced to resign, the president will simply reappoint him. That would do little to restore faith in the political system among those disillusioned by what they see as an old pals' act.

The irony is that if Renzi's reforms go through it will make it easier for Five Star to win an outright majority - an anti-establishment party is likely to gather votes from the left in a play-off with the right and vice versa.

Next year eyes will turn to the all-important elections in France and Germany. Italy could deliver an upset long before then.

- Published1 June 2015

- Published9 July 2016

- Published20 June 2016

- Published13 October 2015