Compassion fatigue and the optician of Lampedusa

- Published

Day after day we are bombarded with images of overcrowded rubber boats in the Mediterranean, horrific pictures of obliterated streets in Aleppo and heartbreaking photographs of desperate people staring through the bars of refugee reception centres.

Occasionally a single image will startle us from our numbed state: Aylan Kurdi's tiny body washed up on a Turkish beach; the bewildered, bloodied face of the five-year-old Syrian boy Omran Daqneesh, sitting barefoot and plastered in masonry dust in the back of an ambulance.

Yet somehow, many of the horror stories of the Syrian war and this migration crisis get drowned out under the weight of their own numbers.

And it's our job as journalists and writers to keep telling those stories and to keep telling them in new ways that will cut through the compassion fatigue and keep our audience and readers focused.

It was last May, when I was reporting largely from Sicily for BBC Radio 4 news programmes, that it became clear to us that our listeners were switching off when they heard the phrase "migrant crisis".

They were doing so not because they were in any way heartless, but because they felt they were hearing the same story, the same pain, over and over again.

The migration story was now so commonplace, it was becoming almost meaningless.

We needed to find a new angle.

So instead of interviewing the migrants themselves, we decided to interview ordinary Italians affected by the situation, as outlined in my book The Optician of Lampedusa.

We spoke to a vivacious housewife-turned-chef in a migrant soup kitchen, a hospital director whose wards were full of burned and brutalised migrant patients and a gravedigger who had the awful task of burying those who washed up dead on Europe's shores.

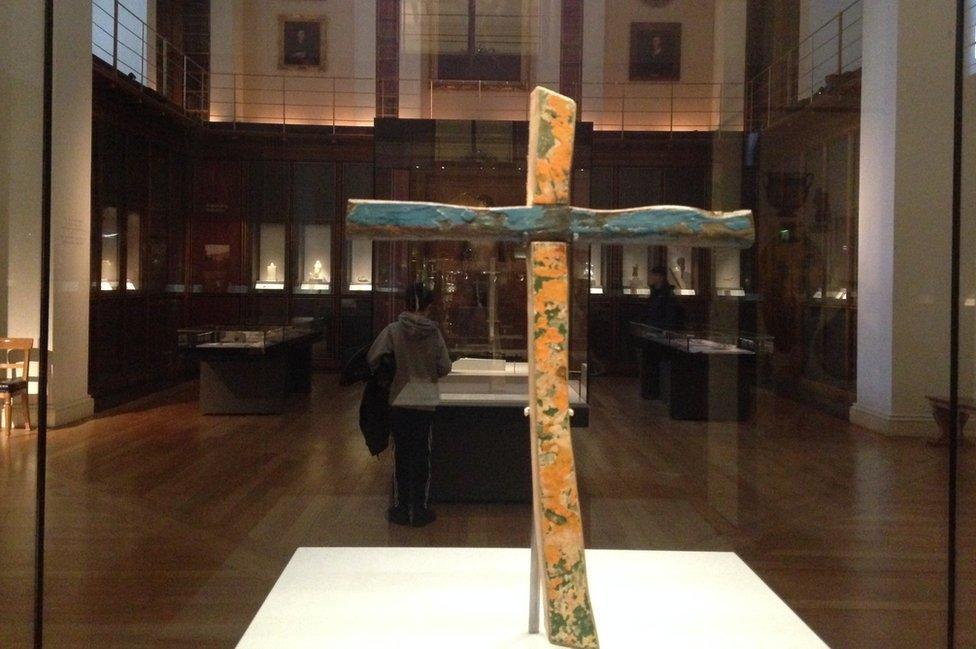

The Lampedusa cross can be seen in the British Museum

We interviewed a carpenter who spent his time carving crosses from shipwrecked wooden migrant boats and offering them to Christian migrants as a symbol of hope and resurrection.

We had an unprecedented response to the series.

Several listeners who were going on holiday to Sicily asked for the address of the migrant soup kitchen so they might devote a couple of evenings helping the chef Maria-Grazia.

Listeners in Africa wrote to us about the tenderness of the gruff gravedigger who never forgot the faces of the nameless bodies he buried.

A curator at the British Museum was so moved by the carpenter's crosses that she ordered one for the collection.

Symbolically it became the last acquisition of the outgoing director, Neil MacGregor.

But one of our stories cut through all the rest.

Carmine Menna runs the only optician's shop on the little island of Lampedusa, off the coast of Sicily.

Although he saw the migrants all around him every day and felt pity for them, he did not really see them - he did not want to see them as his problem.

After all, he was just an optician. What could he do?

368 migrants died in the Lampedusa tragedy

One day in early October 2013, however, he took a boating holiday with his wife and six friends.

He remembers it was a beautiful day and he woke in his bunk to hear what he thought was the first of the seagulls squabbling and screaming over a lucky catch.

But when the noise became more persistent and piercing, he and his crew upped anchor and went to investigate.

They did not find seagulls.

Instead they found scores, perhaps hundreds of drowning people in the water, begging them for help.

The optician was on a boat that had a maximum capacity of 10 and already had eight people on board.

They had only one rubber ring.

Carmine's story resonated enormously with our listeners because he is such an ordinary man - no better or worse than us.

Listeners said that they could imagine themselves in his boat reaching out to grab those desperate hands.

Watching the drama unfold from behind his glasses, they could really see the crisis for the first time.

Suddenly the migration story - and perhaps their own part in it - had become real.

The optician himself told me that it was only when he felt the flesh and bone of the hands he seized grind into his, that the migrants became "names, not numbers - names."

Fishermen lay a wreath in memory of victims of the Lampedusa disaster

That Lampedusa tragedy left 368 people dead.

Carmine is a reluctant interviewee because he does not want to be cast as some sort of hero.

"We saved 47 people that day," he tells me quietly. "A hero would have saved them all."

I was unsure that the shy and discreet Carmine would let me turn his story into a book, but when I approached him to ask his permission he surprised me by readily agreeing.

An optician's job, after all, is to make people see clearly and I think that is exactly why he has allowed me to tell his tale through his eyes.

It does not matter, he seems to be saying, whether you are pro or anti-immigration, or whether you vote left or right.

But it does matter - it has to matter - that thousands of human beings are drowning every year on Europe's doorstep.

We cannot get hardened to this horror of our age.

Listen to Emma Jane Kirby's most recent report for PM on the optician of Lampedusa via the BBC iPlayer.