Italy earthquake: Why so many houses collapsed

- Published

A walk around quake-hit Arquata del Tronto with engineer Graziano Leoni

When Giorgio Adamo woke up in his flat amid the horror of the earthquake that shook central Italy at 03:36 on 24 August, it was the banging of his wardrobe that startled him.

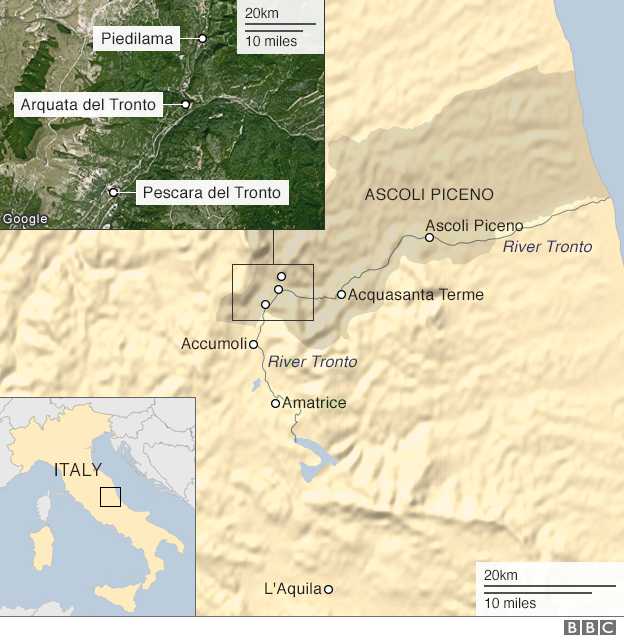

While buildings crashed down throughout the region, claiming the lives of 298 people, many structures like Giorgio's in the town of Ascoli Piceno remained intact. The furniture had moved away from the walls but his flat and the building itself were intact.

His mother, Maddalena, was not so lucky. A few miles up the River Tronto to the south-east, she stayed terrified in her bed as the quake tore down the front wall of her old stone house near Acquasanta Terme.

Giorgio's city building (L) remained intact but the front wall of his mother's country house collapsed (R)

In the villages of Pescara and Arquata del Tronto, houses were reduced to heaps of rubble, killing or injuring their inhabitants.

But there too some buildings withstood the shock. Even if they have since been condemned, they did serve their primary purpose of shelter.

Why did houses collapse?

Settlements in the Tronto Valley have built up over centuries, along the route of an important ancient Roman road, the Via Salaria.

Primarily made of stone, homes were built without the benefit of modern science and renovated more recently with new materials, sometimes with disastrous results.

"When reinforced concrete is used on the roof, its weight causes the masonry to fail because the walls beneath cannot sustain it," says Graziano Leoni, a professor of structural engineering at the University of Camerino, who has been helping assess damage to buildings.

In Arquata del Tronto, lumps of concrete can be seen in the wrecks of the buildings, with old stone walls burst open like seed pods.

Another factor may have been the close proximity of buildings of different ages, the professor believes.

Residents of the valley also fear buildings may have been damaged by loosened rocks or rubble left over from a 6.1 magnitude earthquake that hit the Umbria and Marche regions in 1997.

Much of Arquata del Tronto has become a no-go area

But the local school's modern construction saved it

Two schools in the quake zone suffered different fates. Despite the widespread destruction in Arquata, the village school withstood the shock because of its solid brick-and-mortar construction, although the damage was enough for it to be rendered unusable.

But that was not the case in Amatrice, Lazio, where the supposedly earthquake-proof school collapsed, leading to suspicions of shoddy public construction.

What can be done to make houses safer?

Italy has developed the expertise to build earthquake-proof homes.

In the city of L'Aquila, devastated by the April 2009 earthquake, housing blocks have been built on columns that dissipate the shock from a tremor: a technique known as base isolation.

But with such a vast heritage of treasured historic buildings, the country's challenge is to make safe existing ones too.

One of the easiest ways to do this is to use tendons to secure external walls, the professor explains.

"Another way is to stiffen the flooring systems so that they connect the surrounding walls and produce a kind of box behaviour in the building," he adds.

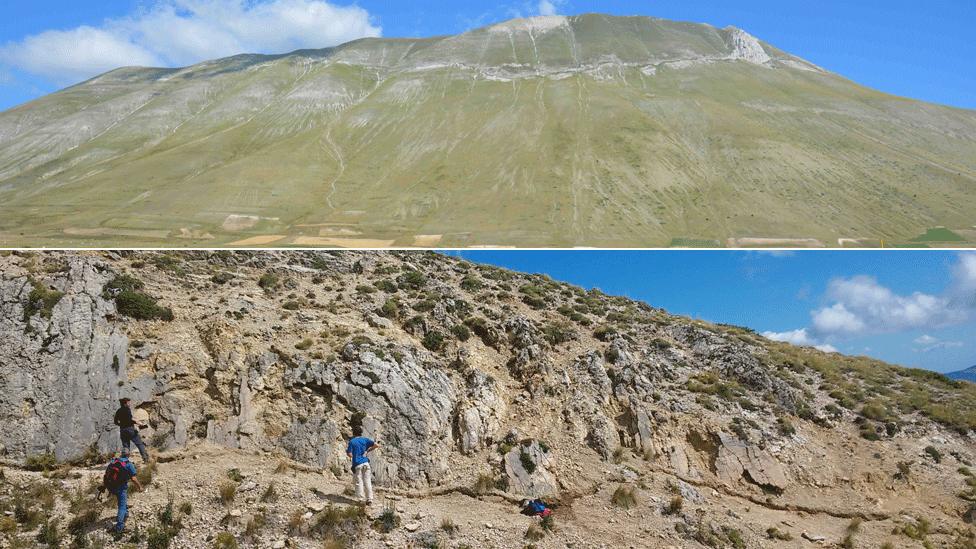

The quake's faultline can be seen at Monte Vettore which overlooks the Tronto Valley

"For scholars of structural engineering, every earthquake is a kind of huge lab test that can give us a lot of information on understanding how old buildings behave and how better to construct new buildings because we have to learn from our past mistakes."

Where will the homeless live?

Maddalena now rents a mobile home close to her ruined house, after initially living in a tent near Acquasanta.

Anyone who lost their home has been guaranteed accommodation by the authorities in Marche region.

Maddalena (C) initially stayed in a tent set up by firefighters from the city of Modena

Giorgio and Maddalena this week

With tents not a viable solution for the Apennine winter, Marche is offering to put people up in hotels or help financially those who find an alternative place to live of their own.

The plan is to build temporary wooden houses within a year for all who need them.

Residents strongly resent any suggestion that houses collapsed because of corruption in the local building industry, an accusation made in cartoons published by French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo.

"Our houses and local structures were built by our grandparents and even older generations, and many people like myself and my mum have tried to renew them," says Giorgio Adamo.

"But the earthquake was really strong and it was just not possible to avoid damage up there. I can tell you there were no mafia involved or architects who did not do their job. It was just fate. It's our grandparents."

They just did not have the skills or expertise to build homes that could stand up to such a powerful earthquake.

- Published30 September 2016

- Published29 September 2016

- Published25 August 2016

- Published27 August 2016