France presidential race: What now for the left and far-right?

- Published

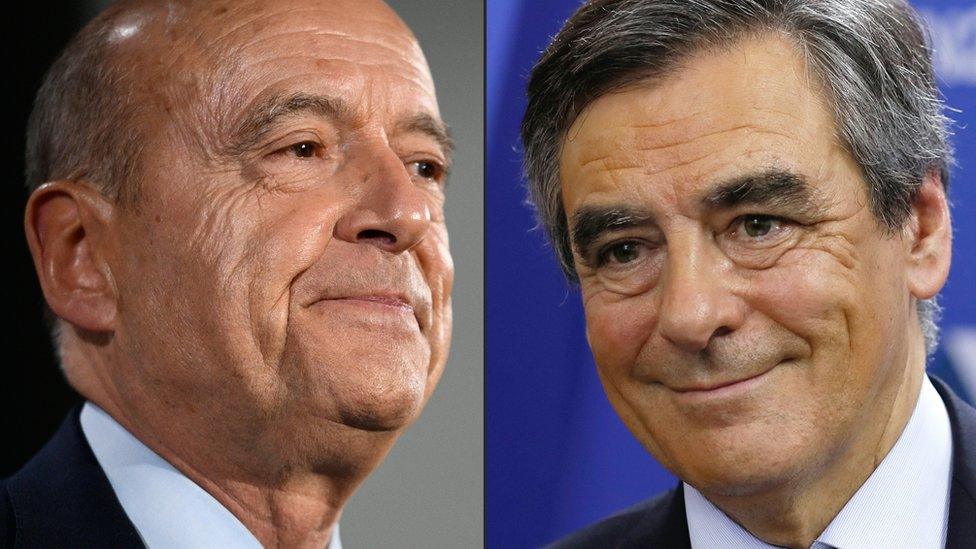

Francois Fillon warned that "France is falling behind"

Francois Fillon has won the centre-right nomination for France's presidential election next year.

The former prime minister received more than two-thirds of the vote in Sunday's run-off, after promising sharp spending cuts, immigration quotas and a "profound transformation" of France.

But where does this leave prospects for the left, and the far-right, on the road to the Elysee?

"I'm going to need everyone," Mr Fillon told a room packed with supporters in central Paris.

"France is falling behind; it wants truth and actions. This presidency has been pathetic. We need to start again as never before."

France has taken its first step towards presidential elections, and chosen Mr Fillon's promise of dramatic change over his rival's offer of more gradual, inclusive reform.

Francois Fillon ran on a platform which included axing half a million public jobs, introducing immigration quotas, and banning full adoption for gay couples.

Whether it was his liberal plans for the economy (he's a fan of Margaret Thatcher), or his Catholic conservatism on issues of French identity and society that won him the most support, he's now the man currently tipped as the favourite for the country's presidential race next year.

Cold comfort

Conceding defeat in front of chanting supporters, his rival Alain Juppe said he was "ending this campaign as (he) started it; a free man, who didn't betray who he was or what he thought".

This was a vote in which anyone could take part, providing they paid €2 (£1.7; $2.12) and signed up to a charter of right-wing and centrist values.

Pollsters say that 15% of Sunday's voters identified as left-wing supporters, many of whom had said they would vote in the Republicans primary to try and boost support for Mr Juppe.

Jean-Luc Melenchon, leader of the far-left, wants to redistribute France's wealth

But there may be cold comfort for the left in Mr Fillon's win because the election of a more hardline candidate to the centre-right opposition leaves the door wide open for other parties to woo left wing voters next year.

Among those lining up to do so is Jean-Luc Melenchon, the leader of the far-left, who wants to redistribute the country's wealth and pull out of European treaties which impose austerity on France.

Watch your back: Will Manuel Valls (right) challenge Francois Hollande?

The Socialist President, Francois Hollande, is due to announce in the next few weeks whether he'll stand for re-election.

But with his approval ratings dropping as low as 4% in one recent poll, many believe his Prime Minister Manuel Valls might have a better chance.

In the meantime, Mr Hollande's former protege and Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron has put himself forward as an independent candidate after launching a new political movement, En Marche (Onwards), which combines free-market reform with a promise to shake up an "empty" French political system.

Not the last surprise?

All might have found themselves competing with Mr Juppe for votes had he won his party's nomination.

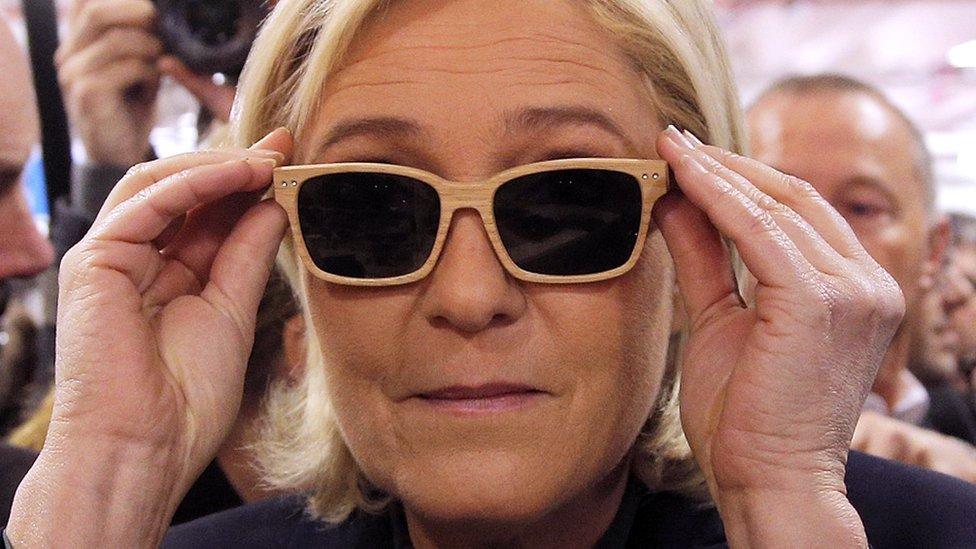

Marine Le Pen is seen as a strong candidate to make it to a presidential run-off in 2017

Instead, it's likely to be the far-right leader, Marine Le Pen, who will be eyeing her centre-right opponent nervously.

The Front National draws its support from disparate sections of French society, and Mr Fillon's positions on the economy and his Catholic background will suit some of her voters, especially those who don't agree with Ms Le Pen's support for gay rights or her proposals to pull France out of the EU.

The fact that Francois Fillon was seen as the "runner-up" for so much of the centre-right primary contest is a reminder of how quickly mood can change, and how difficult it is to predict.

As his team celebrates their win at his headquarters in Paris they'll know that his nomination, while the first surprise in this race, may not be the last.

- Published28 March 2017

- Published26 November 2016

- Published7 December 2016

- Published19 November 2016