What lies in store for the world in 2017?

- Published

What lies in store for the world next year? Some telling recent events suggest it could be very difficult for Western countries.

While at the end of 2015 I looked at the way nationalistic populism would make the job of diplomats harder in 2016, now there are signs that the West's ability even to set the rules of the international game is beginning to unravel.

"The post-Cold War era of Western-led globalisation, US predominance and the comfortable ascendancy of liberal international values is over," says Sir Simon Fraser, head of the UK Diplomatic Service 2010-2015.

"The current stresses on the international order that we've known since the end of the Second World War", argues US General Stanley McChrystal, who commanded Nato forces in Afghanistan 2009-2010, "reflect a decentralization or 'atomization' of power on multiple levels".

Among key events in the latter part of 2016:

Russia's alleged used of hacked information in the US election.

The suppression of rebels in eastern Aleppo by Syria and its foreign supporters, involving large scale use against civilian populations of weapons banned by many countries.

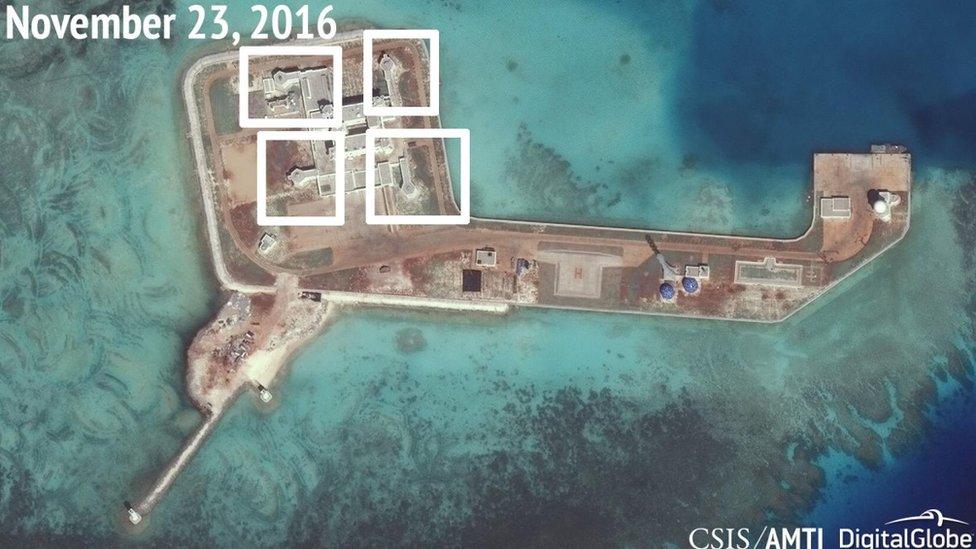

China's decision to ignore a UN Conference on the Law of the Sea arbitration that found against Beijing in a territorial dispute with the Philippines.

The decision by some countries, including Russia and South Africa, to withdraw from the International Criminal Court.

The faltering of some international trade negotiations, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership after president-elect Donald Trump announced that the US was abandoning it.

Syria: the unstoppable war

Events in Syria underline the failure of the UN Security Council's five permanent members (China, France, Russia, the UK and US) to agree any way of stopping that crisis. But in truth, ever since the UN was founded in 1945, the big players have rarely united during serious international crises, and never when one permanent member has felt its vital interests threatened.

The UN's endorsement of the 1991 US-led war against Saddam Hussein was a very rare example of the Security Council actually backing a war, but it was a fleeting moment.

Our recent conception of international order, "was based on an atypical level of American dominance, which was always going to be finite," believes Professor Patrick Porter of Exeter University, who adds, "this order is unravelling from without, as the shift of economic weight from west to east makes it harder for the West to impose its will."

Of course, many will welcome the eclipse of American hyperpower, the sense of global dominance that flourished for several years after the collapse of communism, and the emergence of a more multi-polar world.

In many African or Asian countries, there is also a sense of empowerment as a generation of statesmen educated in Western universities has given way to those with their own world view.

Some African nations are now leaving the International Criminal Court

In the case of South Africa and some other African countries leaving the International Criminal Court or ICC, it's been the result of perceived unfairness, the Gambian information minister saying the court had been used, "for the persecution of Africans and especially their leaders".

Russia and China, both part of the big-power UN club, have recently questioned the UN's competence in relation to territorial disputes they care deeply about.

If old rules seen as being drafted by "colonialists" or powerful westerners now seem less relevant in many parts of the world, they at least embodied a belief system which many countries were willing to agree with for decades, or at least pay lip service to.

Strong emerging ideologies - whether it is China's brand of post-communist/Confucianism, Russia's Eastern Orthodox-influenced sense of national destiny, or the very different Islamic ideas that motivate Saudi or Iranian policy - may appeal to their own people but hardly anyone else.

Rejection of the international status quo is in fact key to many of these national or religious narratives.

Non-national groups (like Hezbollah or Boko Haram to name but two) also pose many challenges.

In security, finance, or technology, new disruptors form such a threat to the established order that, believes General McChrystal, "it is tempting to conjure up a post-apocalyptic vision of no-holds-barred survival of the fittest."

Trump versus Putin: a new age of bilateralism?

While this host of powerful challenges lurks without, there is also what Professor Porter characterizes as, "unravelling from within". The West itself now harbours a good deal of disagreement. For example, the election of Donald Trump has opened new fears of trade wars.

If the president-elect delivers on his various campaign promises, then "we are heading into a period of tough, big power foreign policy: more transactional, more confrontational, driven by power and national interest, rather than values or a concept of international community," argues Sir Simon Fraser.

There is likely to be more emphasis on bilateral (between pairs of states) rather than multilateral diplomacy - and that could give international relations a more 19th Century feel. Professor Porter argues that "we are moving uncomfortably, and unprepared, into a more historically 'normal' diplomacy where we compete and collaborate with other great powers at the same time."

The relationship between Turkish president Reccep Tayip Erdogan and Vladimir Putin is an interesting example of post-ideological statecraft.

They swiftly moved from confrontation and economic sanctions after Turkey downed a Russian jet, to strategic cooperation in Syria in 2016, following a fence-mending summit in St Petersburg.

Chinese military hardware in the disputed South China Sea - the country is ignoring a UN arbitration for the area

But can European countries or the US with their democratic traditions and competing interest groups really be as fleet of foot as those with strong leaders wielding autocratic powers?

Britain's former chief diplomat, Simon Fraser, believes, "laws, organizations, treaties, and other 'rules of the road' will remain essential, but will be likely to take on a new look and feel, continuously morphing within very broad outlines generally accepted by enough of the world to have some credibility."

The world's current tectonics seem to put Western societies at a decided disadvantage: they respect international rulings, while Russia and China say they can ignore them (e.g. Crimea and the South China Sea).

Their armed forces have (in many cases) renounced the use of cluster bombs or mines - weapons used so liberally by Syria and Russia in recent months; and the Western ability to respond in kind to Russian or other politically-targeted cyber attacks is limited, and in any case would be of questionable use against countries where there's broad control over the media.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has warned that a more conditional Nato would work both ways

Add to this the strains posed by economic stagnation, protectionism, and populist rhetoric and you have to ask seriously whether the international clubs central to our definition of "the West" - Nato and the European Union - can survive 2017 in their present form.

A series of elections in Italy, the Netherlands, France, and Germany, could severely test the EU, and in particular the euro.

Regarding Nato, president-elect Trump has suggested future US protection will be contingent on European allies paying more.

And putting caveats on what was once assumed to be a guarantee of help isn't one-sided: German Chancellor Angela Merkel has suggested future cooperation with America will be conditioned by Washington 's "respect for the law and the dignity of man".

In this period of flux there will be opportunities as well as dangers.

But the question now is whether western countries can seize them and become the master of events; or whether they will simply be at their mercy?

- Published8 December 2016

- Published17 February 2016

- Published13 January 2016

- Published26 December 2015