Fears over how US President-elect Trump sees Nato's future

- Published

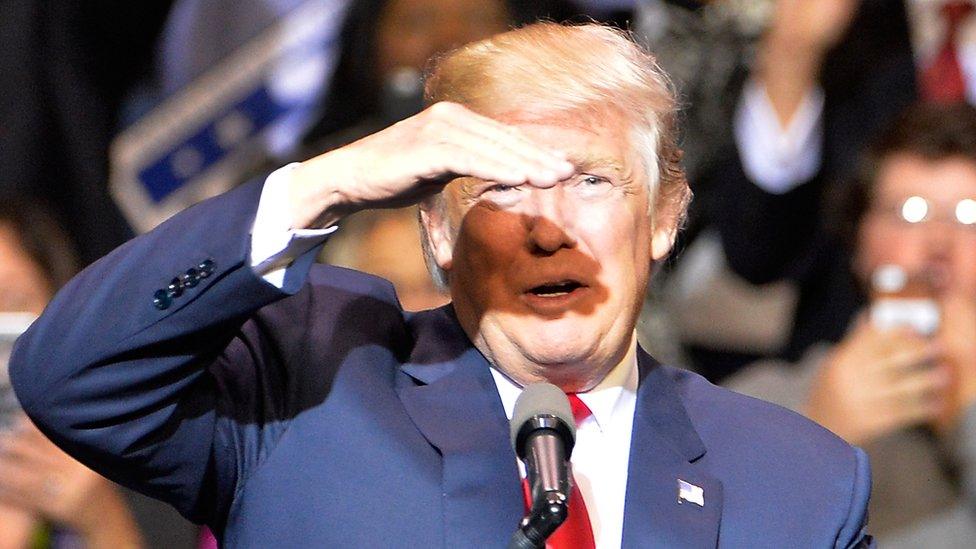

Donald Trump criticised Nato a number of times during his campaign to become president

Donald Trump's policies "could spell the beginning of the end" of Nato, a senior former field commander for the alliance has told Newsnight.

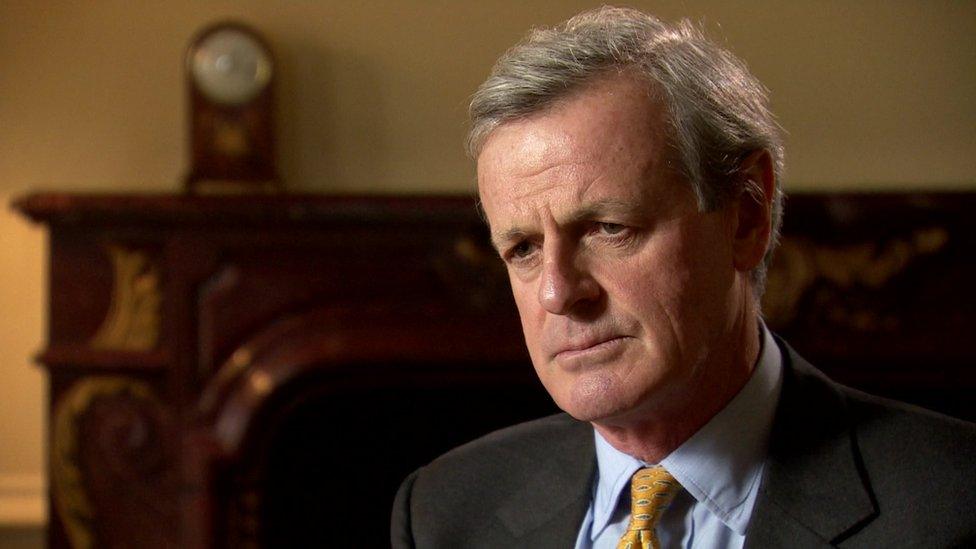

General Sir Richard Shirreff, Nato's deputy supreme commander from 2011-2014, says the US President-elect should re-dedicate himself to the common defence of the western allies soon after his inauguration in January.

The general says Mr Trump must send the "strongest possible signal …that America will, no ifs, no buts, no prevarication, come to the aid of a Nato member if attacked".

If that doesn't happen, Gen Shirreff warns, it "will strike right at the heart of Nato's founding principle of collective defence".

Alexander Vershbow, an American career diplomat who was Nato's Deputy Secretary-General from 2012-2016, says the election of the new president sends a clear signal to European members of the pact who have been under-investing in their defence.

"This was a change election in the United States," Mr Vershbow told the BBC, "so there will be change and I think allies have to be prepared to adapt."

General Sir Richard Shirreff has urged Donald Trump to reassure Nato members

During the campaign Mr Trump said of unspecified Nato allies: "They're not paying their way". He suggested that, if one of them was attacked, the US would be entitled to ask "have they paid?" before deciding to go to their assistance.

The use of this language has caused alarm in many Nato capitals.

There is also concern about suggestions that Mr Trump, as part of a rapprochement with Russia, might be prepared to concede a "zone of influence" to the Kremlin in former Soviet republics, or to reduce pressure over the issue of Ukraine.

"Ratifying the results of Russian aggression in Ukraine would buy you some short term stability," said Mr Vershbow, when asked about the possibility that Mr Trump might accept the Kremlin calling the shots in eastern Europe in return for better relations.

"But I think it would create a much more unstable situation in Europe, encourage the Russians to continue to press forward for some kind of Yalta 2 with a new division of Europe into spheres of influence, which I think would bring back some of the instability we saw in previous decades."

Prior to his Nato role, Mr Vershbow was US ambassador to Moscow from 2001-2005.

At the Yalta conference in 1945, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, US President Franklin Roosevelt and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin agreed on zones of occupation for Europe

Acquiescing to further Russian operations in Ukraine (which is not a Nato member) might send a signal that the president-elect effectively recognises Russia's right to dominate certain neighbouring states, many Nato decision-makers feel.

They fear also a possible knock-on effect in former Soviet republics that are now part of Nato (and indeed the European Union), the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

"There must be absolutely no doubt about the imperative of defending and protecting Nato territory. There must be no discussion or deals about zones of influence, new Yaltas," says Gen Shirreff, "because that strikes right at the heart of what Nato is about".

- Published13 November 2016

- Published25 April 2017

- Published15 December 2018

- Published18 March 2014

- Published25 October 2016