EU summit: My part in the Treaty of Rome signing

- Published

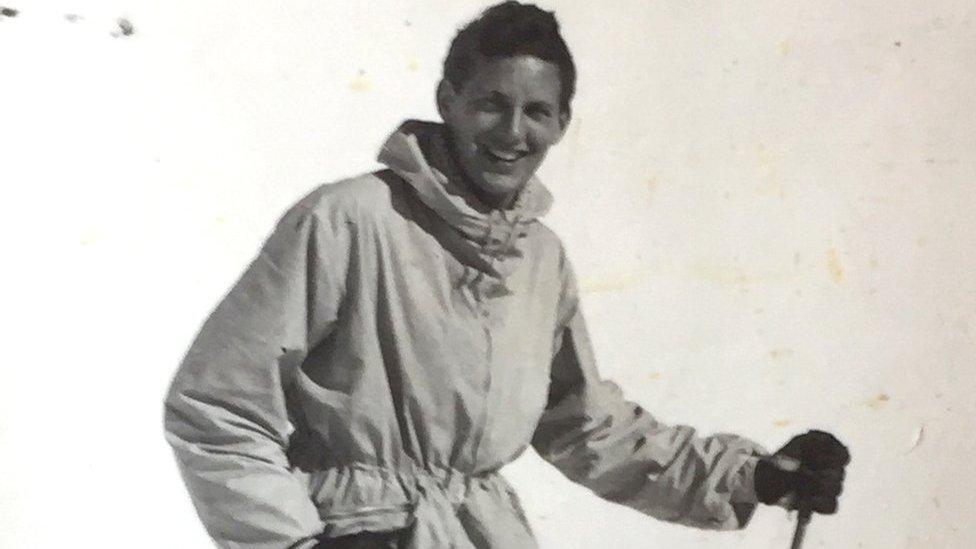

David Willey was a trainee journalist when he covered the treaty signing

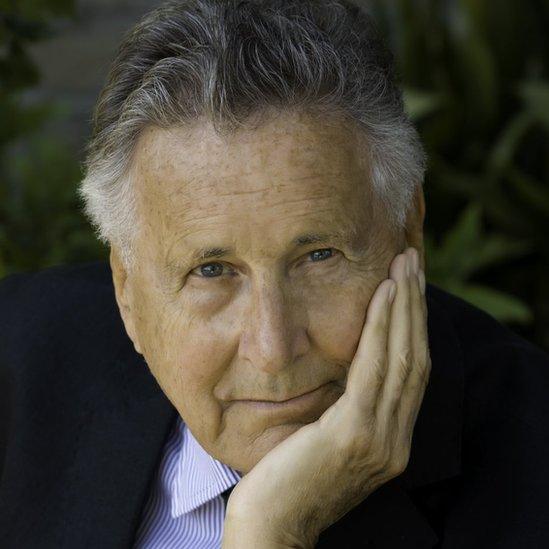

More than 20 European heads of state and government are gathering this weekend in the Italian capital to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Rome. Present on that day was David Willey, later to be one of the BBC's longest-serving foreign correspondents. At the time, he was a trainee reporter learning the rudiments of journalism.

Newsreels of the event confirm my memory that it was raining cats and dogs on that March evening 60 years ago when the founding fathers of the six-nation European Economic Community (EEC) arrived at Michelangelo's great architectural masterpiece Palazzo dei Conservatori on Rome's Capitoline hill.

They included the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer; Paul-Henri Spaak, the Belgian mover and shaker of the new European federal post-war dream; and Walter Hallstein, the German diplomat soon to be elected as the first president of the new community.

They were there to put their signatures to what was to become known as the Treaty of Rome. The document promised what they hoped would be "an ever closer union".

The symbolism was almost overpowering.

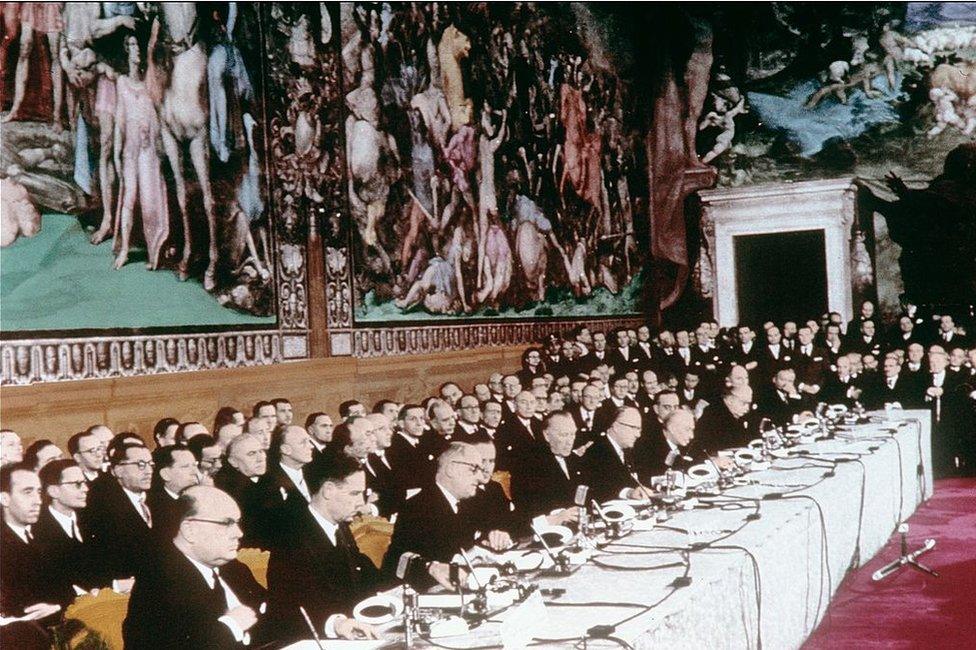

Representatives of "the Six" met in the richly-decorated Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome

They were gathered at the very hub of the ancient world where, 2,500 years ago, six centuries before Christ, the foundations were laid of Rome's first major temple, dedicated to Jupiter, king of the gods.

That massive edifice disappeared many centuries ago, the victim of fire or earthquake, but you can still see its excavated foundations, layer upon layer of carefully piled blocks of greyish tufa, the local building material, near the cavernous frescoed room half the length of a football field, where the treaty signing actually took place.

The fathers of the new Europe were overlooked by two enormous statues of 16th Century popes raised on plinths at either end, one in bronze, the other in marble. The colourful frescoes depict tales of the legendary heroes and founders of ancient Rome.

The ministers and their black-suited advisers sat at long trestle tables and the signatories all said a few inspiring words in Italian, French or German. No-one spoke in English: Britain had been invited to join but had slightly huffily declined.

Only four years later Prime Minister Harold Macmillan would reverse British government policy and make a formal application to join the new European club.

I had been assigned to cover the signing ceremony by the local Reuters news agency bureau where I was a junior trainee reporter. The English media had shown little interest in the story and that was the reason why I was sent along.

I recently checked the report in the following day's Times. It got only a third of a column on page eight. "Historic Date" was the brief headline.

The Vatican newspaper of record L'Osservatore Romano was much more upbeat. It lyrically described the event as "the most illustrious and significant international political event in the modern history of Rome".

Most of Europe's leaders in the mid-50s were Catholics, so the following day the ministers all trooped off for a private audience across the river Tiber with Pope Pius XII, the wartime pope still reigning at the Vatican. His strong attachment to Germany had been honed by long years spent as nuncio, or papal ambassador, in Berlin.

It has emerged that many of the pages inside the copies of the treaty were blank

Pius turned out to be more cautious than his newspaper's editorial about the prospects for changing the already successful European Coal and Steel Community into a full-blown political and customs union.

"At the present time," he said, "many people are of the opinion that it will be a long while before the initial enthusiasm for [European] unification is revived."

What we did not know on that day was that only the first and last pages of the Rome Treaty had actually reached the signatories. The bulky documents on the trestle tables were mostly composed of blank pages.

There had been a last-minute mix-up in sending the final text from the chateau in the Brussels suburbs where ministers had been closeted for months arguing and haggling endlessly about such arcane matters as the shape of bananas to be sold in West Germany.

The Germans liked long fat ones; the French wanted to sell the smaller sweeter ones from their former African colonies. It was all a foretaste of troubles to come.

- Published21 March 2017

- Published20 March 2017

- Published7 March 2017