Turkey referendum: Vote expanding Erdogan powers 'valid'

- Published

Protesters march through the Turkish capital, calling for a recount

The Yes vote in the referendum that grants sweeping new powers to the president of Turkey is valid, the head of the electoral body says.

Sadi Guven was speaking after the main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) cited irregularities, including the use of unstamped ballot papers.

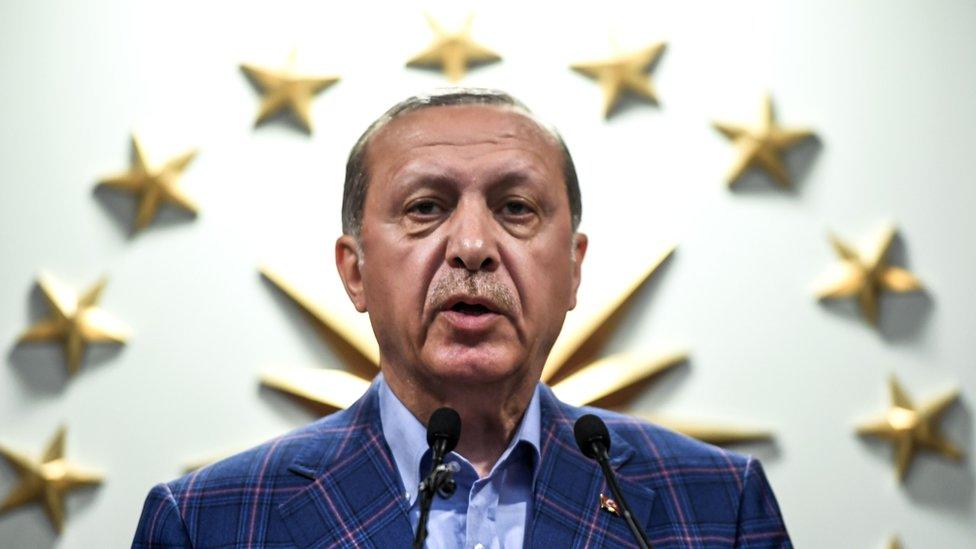

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's push for an executive presidency succeeded with 51.4% voting for it.

Observers said the process had flaws such as campaigning restrictions.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) said the referendum took place on an "unlevel playing field" as the two sides did not have equal opportunities.

"We observed the misuse of state resources, as well as the obstruction of 'No' campaign events," it said in a statement., external

"The campaign rhetoric was tarnished by some senior officials equating 'No' supporters with terrorist sympathisers, and in numerous cases 'No' supporters faced police interventions and violent scuffles at their events."

However, the OSCE said there were no major problems on referendum day, "except in some regions".

Support for Mr Erdogan remains stable, even though big cities did not back the changes

The win was met with both celebrations and protests across Turkey.

Deputy Prime Minister Nurettin Canikli said legal changes to introduce the new system could be completed within a year.

New presidential and parliamentary elections are due on 3 November 2019.

Turnout was said to be as high as 85%.

The CHP has demanded a recount of 60% of the votes. Its deputy head said the result should be annulled altogether. The pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) also challenged the vote.

But Mr Guven said the unstamped ballot papers had been produced by the High Electoral Board and were valid.

He said a similar procedure had been used in past elections.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan: "Decision made by the Turkish public is a historic moment"

Three of Turkey's biggest cities - Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir - all voted No to the constitutional changes.

Opposition supporters took to the streets of Istanbul to bang pots and pans - a traditional form of protest - in a series of noisy demonstrations.

Meanwhile, flag-waving supporters of Mr Erdogan celebrated.

Responding to Sunday's result, the European Commission urged Mr Erdogan, external to respect the closeness of the vote and to "seek the broadest possible national consensus" when considering the far-reaching implications of the constitutional amendments.

Supporters of Mr Erdogan celebrated the referendum result in Istanbul

Profoundly polarised - BBC's Mark Lowen in Ankara

A divisive campaign ended in a contested result. President Erdogan declared victory by a narrow margin and called on every side to respect it. But the opposition has not conceded, claiming voting irregularities. It's clouded the legitimacy of the mandate the president now feels he's been given, to concentrate political power in his hands.

International observers will give their verdict today - that could embolden or weaken the opposition's case and determine how Turkey's western allies will respond.

Mr Erdogan hoped this would be the crowning moment of his career. But it's left Turkey profoundly polarised, at risk of becoming another chronically unstable part of the Middle East.

Death penalty next?

President Erdogan said after the result that Turkey could now hold a referendum on bringing back the death penalty - a move that would end Turkey's EU negotiations.

European Parliament President Antonio Tajani expressed concern about the death penalty move

What's in the new constitution?

The president will have a five-year tenure, for a maximum of two terms

The president will be able to directly appoint top public officials, including ministers and one or several vice-presidents

The job of prime minister will be scrapped

The president will have power to intervene in the judiciary, which Mr Erdogan has accused of being influenced by Fethullah Gulen, the Pennsylvania-based preacher he blames for the failed coup in July

The president will decide whether or not impose a state of emergency

Mr Erdogan says the changes are needed to address Turkey's security challenges after last July's attempted coup, and to avoid the fragile coalition governments of the past.

The new system, he argues, will resemble those in France and the US and will bring calm in a time of turmoil marked by a Kurdish insurgency, Islamist militancy and conflict in neighbouring Syria, which has led to a huge refugee influx.

Critics of the changes fear the move will make the president's position too powerful, arguing that it amounts to one-man rule, without the checks and balances of other presidential systems such as those in France and the US.

Some protesters banged pots and pans in the Turkish capital after the results were announced

Emergency rule

Many Turks already fear growing authoritarianism in their country, where tens of thousands of people have been arrested, and at least 100,000 sacked or suspended from their jobs, since the coup attempt.

Academic voices her fears for her country

Mr Erdogan assumed the presidency, meant to be a largely ceremonial position, in 2014 after more than a decade as prime minister.

Under his rule, relations with the EU have deteriorated. Mr Erdogan sparred bitterly with European governments who banned rallies by his ministers in their countries during the referendum campaign. He called the bans "Nazi acts".

The new system could enable him to remain in office until 2029.

- Published17 April 2017

- Published17 April 2017

- Published16 April 2017

- Published11 April 2017

- Published24 March

- Published30 March 2017

- Published13 April 2017