Why Erdogan's Turkish victory may rally his opponents

- Published

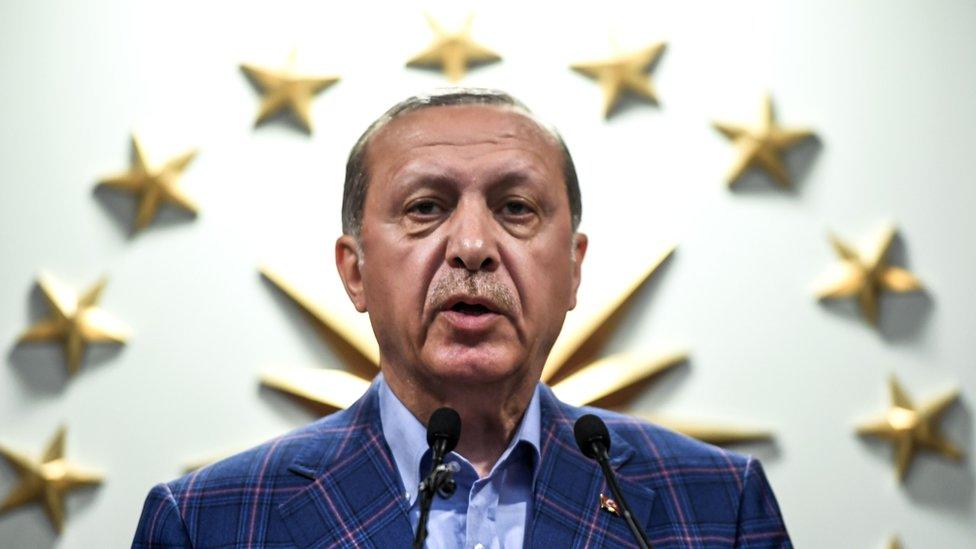

President Erdogan rejected the findings of observers that the vote was held on an "unlevel playing field"

There were only two options: a Yes or a No. The question was missing from the 16 April ballot paper on changing Turkey's constitution.

Expecting millions of voters to answer a non-existent question may seem odd, but it somehow made sense.

Because while the referendum involved 18 articles that would suspend Turkey's separation of powers, the real, unwritten question was: Should Turkey be a one-man show or not?

The Yes-vote was apparently the last piece of the puzzle in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's new Turkey project. But will it actually work?

In the Yes camp were Turkey's ruling AKP and the ultranationalist MHP party. But the result suggests that this attempted merger of the Islamist-rooted government with ultra-nationalism did not work.

Turkish referendum in three words

Ultranationalist voters do not appear to have voted Yes and the Felicity Party (Saadet Partisi), which came out of the same traditional Islamist movement as the AKP, repeatedly said it did not back the Yes camp.

On the other hand, the Yes camp did attract unexpected support in some Kurdish districts, where the AKP used to be strong but lost its grip in 2015 elections. Turkey's big Kurdish party struggled to campaign for a No vote because its MPs and leaders are in jail.

A vote is stamped Yes (Evet in Turkish)

Even though Turkey had struggled to maintain democracy since its foundation, it always had free and fair elections except its first multi-party vote in 1946.

And there was a widespread belief in the No camp that the vote was rigged well before the vote took place. In the words of international observers, "the referendum took place on an unlevel playing field, and the two sides of the campaign did not have equal opportunities".

So when Turkey's High Electoral Board (SBE) announced on the day of the vote itself that unstamped/unauthenticated ballot papers would be counted as valid, the No campaign felt the board had put the boot in.

Read more on referendum:

"No change of rules (is) permitted after the voting has started," says Kerem Gulay of Cornell University. The authority can apply the law but cannot change it, he says.

The frustration of No voters was clear as the number involved - almost 650,000 votes - could have changed the course of a historic referendum. The difference between the two votes was little more than 1.3 million. As we saw with Brexit, a country's future can hinge on relatively small margins.

Opposition could regroup

For all the disappointments of the No campaign, they may see a silver lining in the long term.

Building democracy in Turkey has always been difficult, and the fragility of such institutions as the judiciary and free press has made the task that much harder.

While these ultranationalists backed a Yes vote, many others did not

But while the result means that democratic backsliding is palpable, the situation may be no more worrying than it was before the vote, and may even prove positive.

For a start, the result comes as a huge blow to the leadership of the ultranationalist MHP, seen as failing to respond to their own constituency. That attitude cannot last and could lead to the formation of new right-wing parties or a change in leadership.

The ultranationalists with the key to Erdogan's ambitions

And there could be changes at the secular, opposition CHP as well that would enable alternative voices and parties to flourish.

The No camp was made up of mostly urban, educated, Westward-looking middle-class Turks, as well as secular Kurds and Turkish nationalists opposed to the MHP leadership. Despite their clear differences they found common cause.

An important factor in the rise of illiberal populism has been the lack of a political alternative to fight it.

In that respect, losing by a small margin may prove more useful to the opposition than narrowly winning if its result is to create a more successful avenue for challenging one-man rule.

Ezgi Basaran is a journalist and co-ordinator of the Turkey programme at St Antony's College, Oxford.

- Published17 April 2017

- Published17 April 2017