Yuri Drozdov: The man who turned Soviet spies into Americans

- Published

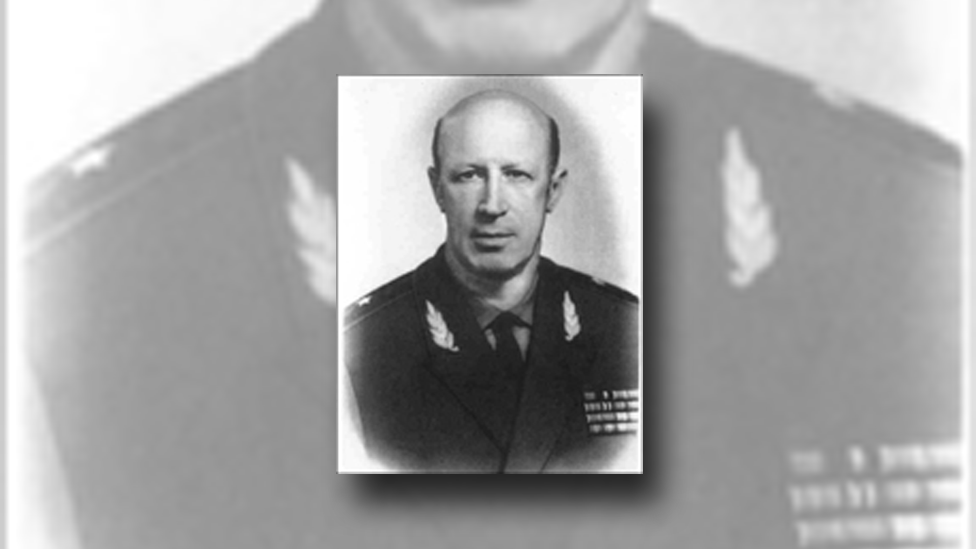

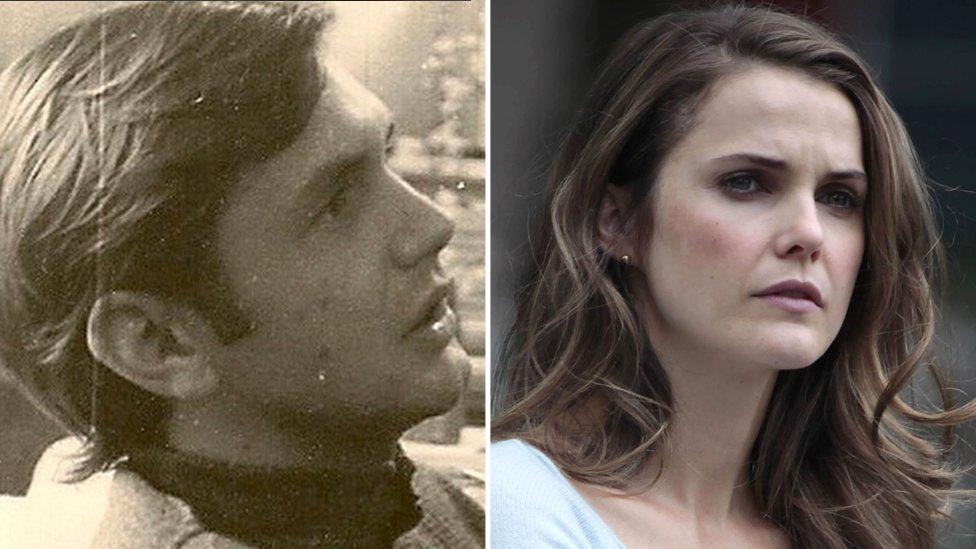

Yuri Drozdov had a legendary reputation in Soviet and Russian intelligence circles

Yuri Drozdov once said it could take up to seven years to train an "illegal", the Soviet spies planted abroad under false or assumed identities, sometimes for decades.

As former chief of the KGB intelligence agency's Directorate S, which managed the illegals programme, Drozdov knew more than most about what it took to prepare someone for the task.

He had to train Soviet agents to talk, think and act, even subconsciously, like the regular American, Brit, German or Frenchman they would become from the moment they touched down on foreign soil.

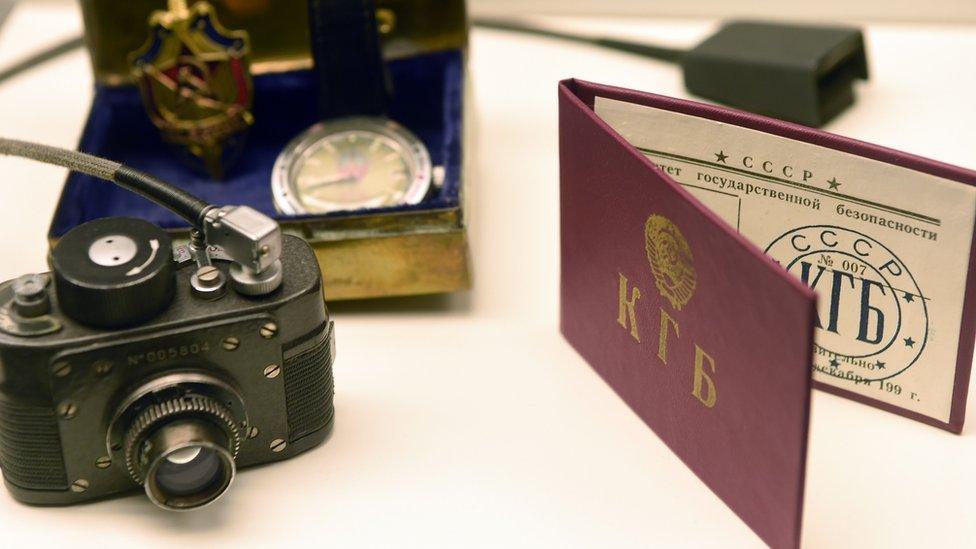

KGB agents in the US and elsewhere would wander around cemeteries in search of children who had died that would have been a similar age as recruits being trained. It was a useful way to steal a real identity in a pre-internet age.

A detailed "legend", or biography, would be devised, and a birth certificate printed. Churches would be paid off to erase the death record.

It was expensive, painstaking work. Some would-be illegals were trained for years, but ultimately judged unsafe to deploy.

Speaking Russian in one's sleep was grounds for a promising recruit to be dismissed.

'There should be no contact'

Drozdov died on 21 June at 91 years of age. It was the end of the life of a man who spent decades in the upper echelons of the KGB and carved out a legendary reputation from his time heading one of the most secretive and infamous programmes in Soviet intelligence.

Unlike "legal" spies, who were posted abroad under diplomatic or other official cover, illegals were on their own - working normal jobs, living in suburbs and operating without the diplomatic immunity enjoyed by other agents should they be caught.

Have you got what it takes to be a spy?

The KGB spy who lived the American dream

In a 2010 interview, Drozdov described a pair of illegals - a man and a woman - deployed to the US via West Germany and posing as a couple.

"When I worked in New York, I would sometimes come around their house. I would drive past, look up at their windows," he told the Rossiiskaya Gazeta newspaper.

But he didn't go inside - the risks being too great for such face-to-face meetings. There should be "no contact with illegals", he said. "None."

"This kind of double life wears on you"

Information gathered by these "deep cover" agents was funnelled back to handlers through clandestine means - including dead-drops, by radio, or covert meetings abroad.

Announcing Drozdov's death, the cause of which was not specified, Russia's Foreign Intelligence Service, the SVR, described him as "a true Russian officer, a decent man, a wise commander".

But much remains unknown about his life and operations he was part of, the details hidden in Russian security archives.

Bridge of Spies

Drozdov was "a legend" in the KGB First Chief Directorate, and still is considered as such in the SVR, says Mark Galeotti, a senior researcher at the Institute of International Relations in Prague and an expert on Russian security affairs.

His father was in the Bolshevik worker militias known as the Red Guards and he served in the Second World War as an artilleryman.

Graduating from the Military Institute for Languages, a key finishing school for Soviet spies, Drozdov joined the KGB in 1956.

Rudolf Abel, the most famous illegal, was arrested in New York in 1957 and later famously exchanged with the USSR in return for the captured US pilot Gary Powers on a Berlin bridge in 1962.

Yuri Drozdov, then a young KGB agent based in East Germany, helped organise the swap, the subject of Steven Spielberg's 2016 thriller Bridge of Spies.

The 1962 swap took place on the Glienicke bridge, which connects West Berlin and Potsdam

Later, in 1975, after a stint in China, he became the "rezident" - or chief KGB officer - at the Soviet Union's UN office in New York, before taking up his position as head of Directorate S in Moscow four years later. After retiring in 1991, he ran a consulting firm.

The Bridge of Spies episode was not the first time Drozdov would be on the ground for a key moment in Cold War history.

In December 1979, he led KGB forces that stormed the Afghan presidential palace toppling President Hafizullah Amin, paving the way for the Soviet invasion.

"This was a guy who spanned the ultra-cerebral world of the spymaster and the action man world of Spetsnaz [special forces]," Mr Galeotti says.

He would later, in 1981, instigate the creation of a new KGB special forces unit called Vympel.

Behind enemy lines

Drozdov's penchant for "hands-on" work is clear. "I would not give top marks to Nato's Special Forces, nor to the American system of training," he said in a 2011 interview. "What they do is try to carry out their special operations without 'getting their hands dirty', and that, to my mind, is a rather dubious business."

He also described caches of equipment hidden in "a number of countries" for sleeper agents to use behind enemy lines in the event of a crisis.

"Whether they are still there [or not], let that be a headache for foreign intelligence services," he said.

Illegals operate without diplomatic cover and blend in like ordinary citizens

Much remains secret about the illegals programme, including the number of people involved. It is estimated that hundreds may have been planted in total by the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Vadim Alekseevich Kirpichenko, Yuri Drozdov's predecessor at the top of Directorate S, described them as agents "artificially created by us", who return to Russia after years of covert service abroad and often speak their native language with an accent.

What recruiters looked for in an illegal was "bravery, focus, a strong will, the ability to quickly forecast various situations, hardiness to stress, excellent abilities for mastering foreign languages, good adaptation to completely new conditions of life, and knowledge of one or several professions that provide an opportunity to make a living," he told the journalist Konstantin Kapitonov, according to the online Espionage History Archive, external.

But other traits, "ones that are elusive and hard to transmit into words, a special artistry", are also required to be able to forget one's identity and become someone else.

Long read: The spy with no name

While the deployment of deep-cover agents to try and obtain information and get close to powerful people makes much less sense in today's digital world, the demise of the Soviet Union did not signal the end of the illegals programme - and Drozdov's legacy lives on to some extent.

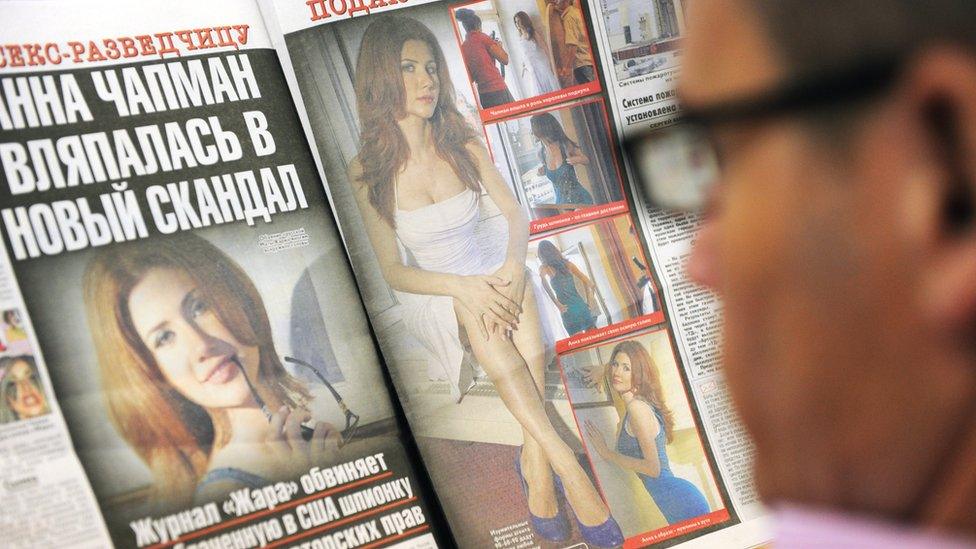

In 2010 a group of 10 Russian "sleeper agents" were arrested in New York. Some lived as couples and had grown-up children, external.

The story inspired hit US TV show The Americans, which portrays the life of a Russian spy couple working as travel agents in American suburbia by day and setting honey traps and assassinating people by night.

Anna Chapman was one of the "sleeper agents" sent back to Russia from the US in 2010

The group caught in real-life have been mocked for their ineptitude, however, and were reported not to have actually obtained any secrets.

They were later swapped with Russia for four Russian nationals said to have worked for Western intelligence.

But other alleged modern-day illegals have popped up elsewhere, including in Spain, external.

"It's certainly a diminishing aspect [of Russian spycraft]," says Mr Galeotti, "but obviously where you have people already in place, unless you have a reason to do so, you leave them there just in case."

- Published29 June 2010

- Published23 February 2017

- Published28 November 2015

- Published6 June 2016