Refugee children on Lesbos helped to face fear of drowning

- Published

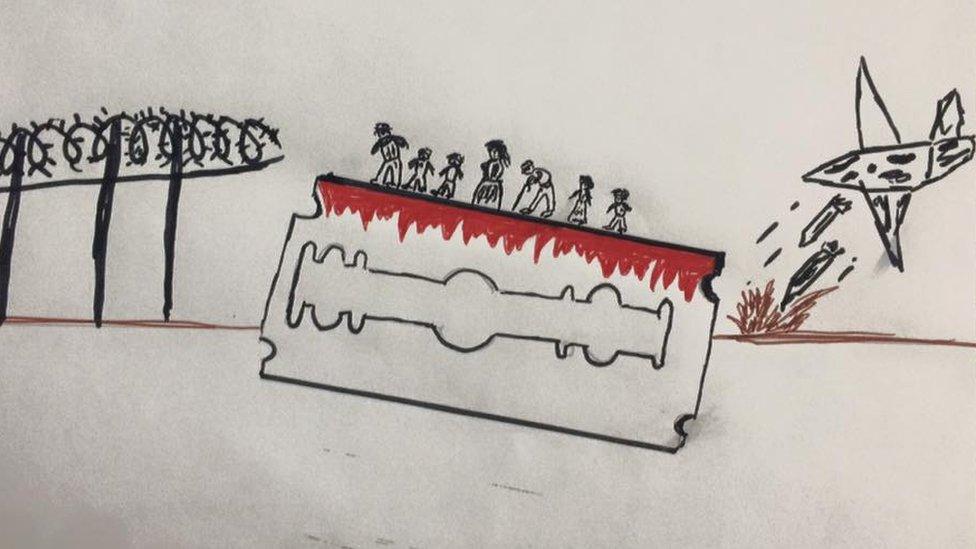

Drawings like this one prompted Lesbos volunteers to treat children's water trauma

"I call it reconciliation," says Manuel Elviro. He is part of a Spanish volunteer group that felt compelled to act after seeing some of the dramatic drawings by children who survived the perilous sea crossing from Turkey to Greece.

"There were monsters in the sea and people drowning."

The volunteers' task was to try to entice traumatised children on the island of Lesbos back into the sea to help them tackle their fears. As well as the terror of the crossing, the children had depicted the war zones they had fled and the filth of the refugee camps, rife with violence and sexual abuse.

They say the sessions are not so much swimming lessons but a "reconciliation" with the sea

"Worst of all, they drew hopelessness," recalls Mr Elviro, a technology researcher from Spain's Balearic Islands University who volunteered for charity Proem-aid, external.

"As I am from Mallorca, a Mediterranean man, I love my sea. It was like an affront. We had to do something."

In 2016, some 173,000 people reached the Greek islands from Turkey. At one point, 2,000 migrants and refugees were reaching Lesbos every day and Proem-Aid says it saved about 50,000 lives.

About 1,300 migrants have been sent back to Turkey since the EU deal in 2016

But an EU deal with Turkey last year has dramatically slowed that number to an average of up to 70 a day. The "pull factor" that some accuse NGOs of providing to migrants off the coast of Libya is not currently an issue on Lesbos.

The period of relative calm gave the group more time to work with survivors in makeshift immigrant camps such as Pikpa, home to some of the most vulnerable individuals who have lost relatives or suffer disabilities.

This drawing depicts those fleeing war walking atop a razor blade

"Many of the children are from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, and had never seen the sea before. It's a hostile environment for them," says Lara Lussón, a volunteer who left her native Madrid for Lesbos in January.

'Blue no good!'

For Sahaar, 15, and her five-year-old brother Satria, their journey from Afghanistan to the gates of Europe ended in tragedy when their mother and two brothers aged eight and 12 were washed overboard.

"Sahaar screamed every time she saw the water," says Manuel Elviro. "They were like koalas, clinging to us, saying 'Blue no good, blue no good'."

"Now the danger is that they will get hypothermia because we can't get them out the water," he laughs. "Sahaar said 'I'm going to Turkey', and I had to grab her by the leg and pull her out."

Child psychologists believe the best way of dealing with such trauma is to confront it

The volunteers work with about a dozen children at a time on spring and summer afternoons, when the water is warm. "They are not swimming lessons; it's not like a summer camp," he explains.

Adam, a six-year-old Iraqi Kurd, arrived at Pikpa camp with an eye problem. His eyelids were glued together, possibly due to exposure to chemical munitions.

"We took him to the water to relax him while his eyes were getting better."

Does water therapy work?

The best treatment for trauma is to confront it, argues Essam Daod, a child psychiatrist and co-founder of Humanity Crew, an NGO that addresses mental health issues among migrants in Greek camps.

"Swimming gives them a sense of control where they had none and fear was the sole master," Dr Daod told Spanish website eldiario.es.

Manuel Elviro tells the story of a Syrian boy who lost his entire family in a bombardment.

"He told me: 'When I come with you to swim, that night I can sleep all right'."

The idea has recently been extended to include some of the children's mothers. The man-free sessions, known as "women's own water" have benefited migrants like Fahtia, who arrived from Somalia with a new-born baby.

Volunteers on trial

The work of the Spanish charity off the shores of Lesbos is not without controversy.

Three Proem-Aid volunteers will face jail terms of up to 10 years if a trial due next April upholds charges of people smuggling and possession of illegal weapons.

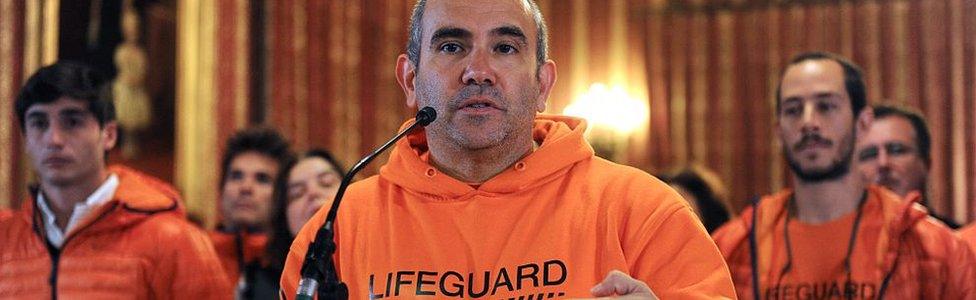

Volunteers Enrique Rodríguez, Manuel Blanco and Julio Latorre (L-R) could face jail

Manuel Blanco, Julio Latorre and Enrique Rodríguez, all firefighters from Seville, were arrested by Greek coastguards in January 2016 on the waters off Lesbos as they were mounting a search-and-rescue mission for migrants.

The Greek authorities consider that the knives the Spaniards were carrying constitute "illegal weapons". The volunteers argue the knives were the minimum blade length required to cut through ropes, nets or other material when rescuing people from the sea.

Two Danish volunteers were arrested at the same time.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published23 July 2017