Turkey's trauma after night of the tanks

- Published

During the failed coup a man was run over twice by a tank and a crowd of people rushed to help

Sabri Unal bears the scars of Turkey's failed coup - quite literally.

On the night of 15 July last year, he joined thousands on the streets to resist the rogue soldiers attempting to seize control.

"I saw tanks approaching - so I threw myself to the ground to block the first one", he said, pointing out the spot on the busy road. "It didn't stop and it drove over me."

CCTV footage showed the miraculous moment that Sabri got up, the tracks of the tank having passed either side of him. Then a second tank came. He tried again - but this time it drove over his arm.

Sabri still bears the scars of the night he was run over by a tank on 15 July

"I wasn't scared and I don't regret it," he told me. "I came here for the sake of God - to gain his blessing."

He initially feared the doctors would amputate his arm. After a skin graft and three months in hospital, the scar covers half of his arm.

"To have been a hero, I would have had to stop the tanks", Sabri said. "I could have done far more."

It is just one of the iconic stories from arguably the gravest ever attack on the Turkish state.

Rebel troops bombed government buildings, including parliament, and opened fire on civilians.

At least 260 people were killed but by dawn, the coup had collapsed.

Turks took to the streets to challenge the heavily armed rebels as the coup unfolded

A year on, the aftermath still convulses Turkey.

More than 50,000 people have been arrested and about 150,000 dismissed or suspended, accused of links to the alleged mastermind: the US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen, who denies any involvement.

His followers indeed worked in every corner of society - business, academia, the civil service and the media - but the government has been widely criticised for seizing the opportunity to crush all opponents, not just the plotters.

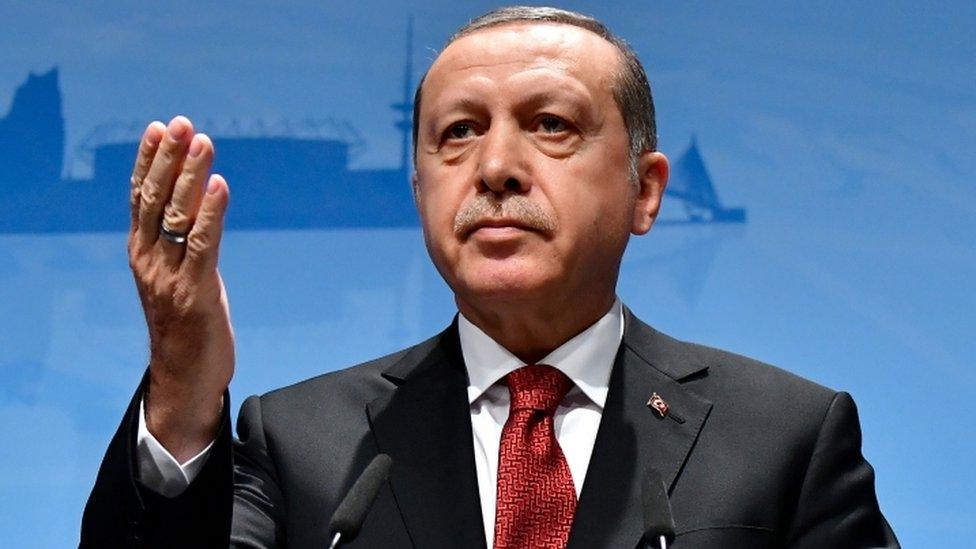

President Erdogan called the coup attempt "a gift from God".

"There is a commission to look at all the cases of those separated from the state", Deputy Prime Minister Mehmet Simsek told me. "If there have been mistakes, the commission continues to rectify it. We have already reinstated thousands of civil servants."

He insisted that the government was acting lawfully in its response to the attempted putsch.

"We are actually saving Turkey's democracy, rule of law and future from a power-hungry criminal network," he said, referring to the Gulen movement. "Nobody questioned the US after 9/11. The United Kingdom has suffered acts of terror and there's been a response to that."

Mark Lowen asked Turkey’s Deputy Prime Minister Mehmet Simsek about the year since the coup

I put it to him that no Western government facing terror attacks has arbitrarily dismissed tens of thousands of people without charge and imprisoned 150 journalists.

"Why don't you give Turkey the benefit of the doubt?" he asked. "Turkey deserves some empathy - it has been through a lot. You will ultimately see that democracy and the judiciary are working here."

Where are they now?

Some caught up in the purge have simply disappeared.

At home in Ankara, Emine Ozben broke down as she told me of her husband, Mustafa, who taught at a Gulen-linked university.

Emine Ozben last saw her husband Mustafa Ozben in May

On his way home in May, eyewitnesses say he was bundled into a car by masked men. He hasn't been since and the police have offered no information.

Several other families have also reported similar kidnappings.

It is a dark reminder of the 1990s, when many Kurds disappeared at the height of the conflict between the Turkish state and Kurdish militants.

"I pray he's alive," said Emine, sobbing beside her six-month old daughter. "I don't believe he backed the coup. If they want to prosecute him, do it legally - not by abduction. I can't raise my children without their father."

Challenging the purge

Others are trying to fight back, although under a state of emergency, resistance is limited.

There are regular protests in Ankara to support two academics, Nuriye Gulmen and Semih Ozakca, who have been on hunger strike for over four months to demand their jobs back.

They were struck off on alleged terrorism charges but given no details of any evidence against them, and later detained.

Esra Ozakca (R) has gone on hunger strike in support of her husband

The protests take place next to a human rights monument, itself sealed off and under police guard: a bleak metaphor for what has happened to Turkey.

Semih's wife, Esra, is also on hunger strike in solidarity.

"One day, your name is on a list and you're struck off," she told me, before she too was arrested. "Your life is turned upside down - you're killed off by the system."

Are Semih and Nuriye prepared to die for this cause, I ask.

"They want to live but for their demands to be met. I can't think of the alternative."

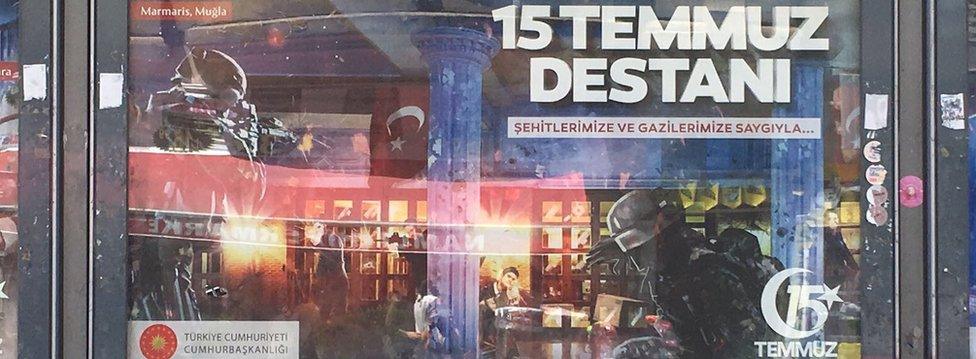

Posters in Istanbul proclaim the heroes of "the legend of 15 July"

A life-and-death protest in the heart of a country trying to join the EU; an unprecedented nationwide purge; a bloody coup attempt and repeated terror attacks: Turkey's descent in the past three years has been extraordinary.

Across the country, posters have gone up for the coup commemoration: slightly kitsch drawings of people confronting soldiers, beneath the motto "the legend of 15 July".

For some, it marked Turkey's rebirth - a glorious moment in their history. But for others it is a painful chapter that is still being written.

- Published17 July 2016

- Published12 July 2017