EU migrant crisis: Austria can deport asylum seekers, court says

- Published

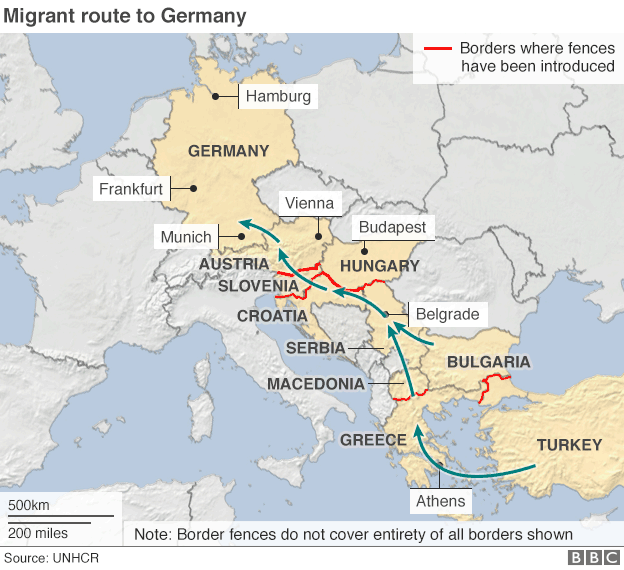

In 2015, hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees crossed from Hungary into Austria

The EU's top court has ruled that a law requiring refugees to seek asylum in the first country they reach applies even in exceptional circumstances.

The case, brought by Austria and Slovenia, could affect the future of several hundred people who arrived during the migrant crisis of 2015-16.

The ruling concerns two Afghan families and a Syrian who applied for asylum after leaving Croatia.

The court says it is Croatia's responsibility to decide their cases.

The crisis unfolded during the summer of 2015, as one million migrants and refugees travelled through the Western Balkans.

Under the so-called Dublin regulation, refugees typically have to seek asylum in the first EU state they reach. But Germany suspended the Dublin regulation for Syrian refugees, halting deportations to the countries they arrived in.

From August 2015, hundreds - and sometimes thousands - arrived in Austria every day, initially via Hungary and later through Slovenia.

Many wanted to travel on to Germany, but around 90,000 applied for asylum in Austria, equivalent to about 1% of its population.

The Afghans rejected by Austria

Among them were two Afghan sisters, Khadija and Zainab Jafari, and their children who arrived at the Austrian border in February 2016.

According to Stephan Klammer, a lawyer from the Diakonie charity, "they came through the organised transports from the Austrian and other governments".

In 2015, the equivalent of 1% of Austria's population applied for asylum there

"They came from Macedonia in a few days directly to Austria. At the Austrian border the Jafari sisters were allowed in because they said they wanted to go to Austria and ask for asylum," he said.

But unlike many other Afghans, they were not granted asylum.

The Austrian authorities eventually decided that they should be deported back to Croatia, their point of entry to the EU, under the Dublin regulation.

Mr Klammer said: "In some cases, the authorities said 'We are not responsible because of the Dublin procedure, Croatia is responsible'. So the Jafaris got this decision."

The Jafari sisters' case was taken to the European Court of Justice (ECJ), along with a similar incident in Slovenia involving a Syrian national.

On Wednesday the ECJ ruled that their crossing of the Croatian border had to be considered irregular under the Dublin rule. Just because one EU country allows a non-EU citizen to enter its territory on humanitarian grounds, that authorisation is not valid in other EU countries.

Austrian lawyer Clemens Lahner said that hundreds of asylum seekers would be affected by the ECJ's decision. "For those already in Croatia - 700 or so - for them the story is over. Austria won't take them back."

But the fate of others is unclear.

Farzad Mohammadi from Afghanistan came to Austria in February 2016 when he was 17 years old. He was deported back to Croatia last November.

"It was very difficult. I had tried so hard. I was in a choir, I played football, I was doing a German course, I did everything I could, but they said that is the law - you have to go," he told the BBC.

However, he was allowed to return to Austria pending the court decision.

Mr Mohammadi in Austria is unclear as a result of the ruling

"Croatia was very bad, worse than Austria. We only had a thin blanket, there were problems with the heating. The toilets were dirty. Very very difficult."

In its ruling the ECJ stressed that EU countries could show a "spirit of solidarity" under a sovereignty clause that allows member states to examine asylum applications even if they do not have to.

Lawyer Clemens Lahner told the BBC that for "those whose asylum claims have been frozen, technically they can be sent back but the court reminds states they can show solidarity or leniency".

Relocation policy still in dispute

In response to the big migrant influx, the EU agreed to relocate 160,000 refugees from Italy and Greece, the two countries that have seen the biggest number of arrivals.

However, only 24,600 people have been relocated so far, according to an EU report, external published on Wednesday.

Although the pace of relocations has improved, two countries have refused to take any refugees, Poland and Hungary. The Czech Republic has not taken anyone since 2016 and Austria has only recently agreed to accept refugees.

Hungary along with Slovakia and Poland called for the relocation policy to be scrapped, but their complaint received a setback from an ECJ legal adviser on Wednesday.

The advocate general recommended that the objection be thrown out, partly because the policy helped "relieve the considerable pressure on the asylum systems of Italy and Greece following the migration crisis in the summer of 2015".

The EU's migrant influx: 2015-16

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published25 July 2017