Is Germany's migrant crisis over? One city put to the test

- Published

Asylum applicant Khaled Kohestani at work in Oberhausen

"Oberhausen is my home now," says Khaled Kohestani. "A lot of things have happened since I arrived here two years ago."

Khaled, 24, first spoke to the BBC 16 months ago. Everything in Germany was new to him. He was scared of getting on the bus. "Everybody is so quiet, no one speaks or say hello, I'm scared of doing something illegal, we don't know the rules and we can't speak to anyone."

Khaled lived in a refugee centre for three months but now has accommodation and a job

Khaled is not scared anymore. We meet him in a metal workshop, where he's grinding and polishing iron doors and garden tables, sending sparks flying. "Things are much easier today, mainly because I speak German now, nothing really is a problem because I understand what people say."

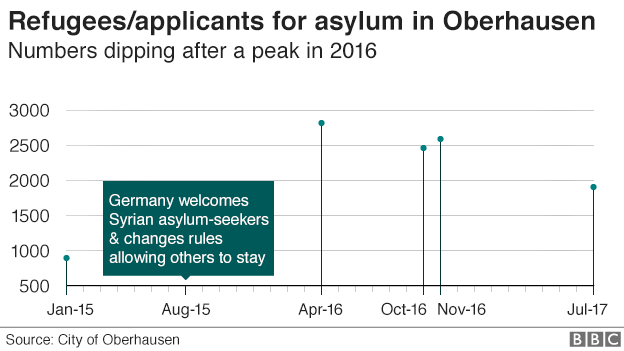

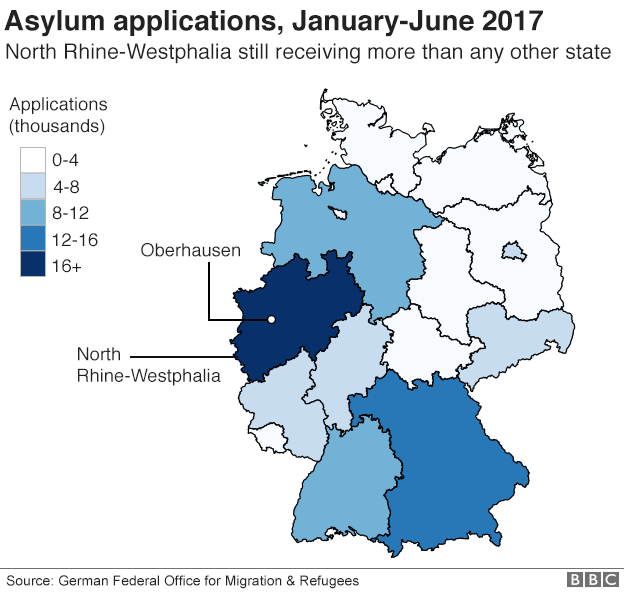

Khaled is an exception. Out of the 1,902 asylum seekers living in Oberhausen, North Rhine-Westphalia, only 42 are, like him, employed or doing an apprenticeship.

But that is no guarantee that he'll be allowed to stay. In January this year, his asylum application was rejected by the German authorities. Khaled and his lawyer have appealed against the decision but Afghanistan is considered a safe country and Khaled and his family could be deported if the appeal is rejected.

No more fights

Two years on from the big influx of migrants and refugees into Germany, things have calmed down and reception centres are operating below their full capacity.

A man in his forties selling curry-wurst for a couple of euros in a small food market on the edge of Oberhausen says when the migrants started coming to Germany there was a lot of noise about what might happen. But for him the city has not really changed in that time, and it does not feel as if there are more foreigners than before.

Oberhausen and the migrant crisis

Chief police inspector Tom Litges says initially the city's reception centres were overcrowded and it was not unusual to be called out to break up fights among the migrants. But things are calmer these days.

"The small protests against migrants and refugees have also have stopped. They used to be massively outnumbered by pro-migrant demonstrators anyway," he points out.

The German Red Cross organises activities for children living in Oberhausen's refugee centre

On Duisburg street, a Turkish artist paints a wall with a dozen children living at a refugee centre. They are colouring jolly characters that seem to come out of a comic book.

Election posters everywhere

Germany is nearing the climax of its general election campaign, but immigration is no longer the hot national issue it once was.

"The situation is now much calmer for everybody and I don't think that the refugee crisis of 2015 will have an impact," says Joerg Fischer from the German Red Cross, who was on the front line in 2015 when emergency camps had to be opened to accommodate everybody.

Voters go to the polls on 24 September and Martin Schulz is challenging Angela Merkel for the job of chancellor

"If the elections had taken place 18 months ago it would clearly have benefited the far right but two years ago Angela Merkel said 'Wir schaffen das' - we will do this - and indeed we did it."

"Oberhausen has received more migrants and refugees than any other region. We'll probably start receiving more people in the autumn again so we are using this time to start integration programmes, we now have a football team, cooking classes for men and empowerment classes for women as well as art workshop for the kids."

On the high street in central Oberhausen elections posters are everywhere, but to the newcomers the election campaign is barely noticeable.

"It's so quiet," says Osmane, a 20-year-old from Guinea. "It doesn't look like its elections time here. In Africa it's chaos during electoral campaigns, you can get mugged for no reason. It is peaceful here, I like it."

With just over two weeks to go before the vote, the anti-immigrant party Alternative for Germany (AfD) is expected to enter the federal parliament for the first time.

Threat of deportation

Whoever wins the federal election will make little difference to Khaled's future in Oberhausen. He says his life is in Germany now rather than Afghanistan and vows to do everything he can to stay. "My son goes to the kindergarten, my wife is learning German and I've got a job."

"German people are always on time everywhere so I try to be punctual, I want my boss to be satisfied with me." And for now that seems to work.

"His German still needs to improve but he's doing well and he is a reliable worker," says Frank Kalutza, who gave him his first job.

The decision for now is out of Khaled's hands and could take several more months. "I don't want to leave, there is nothing in Afghanistan for me."

Khaled is one of only 42 refugees who are in employment in Oberhausen

- Published6 September 2017