German election: Why so many voters in the east chose AfD

- Published

Alternative for Germany (AfD) says Islam does not belong in Germany

Alternative for Germany supporters in the north-eastern town of Schwerin are toasting success in Sunday's election. "To AfD! May it grow and prosper!"

It's their time now. Almost one in five voters in this region backed the right-wing nationalist party. Across Germany as a whole, the figure was 12.6%.

Just four years after it began as an anti-euro party, AfD has claimed 94 seats in the federal parliament, winning over voters with its populist anti-immigration and anti-Islam stance.

In Schwerin, the table is packed with cakes and cookies, and decorated with a small German flag. There is a clink of glasses.

As they sip their German sparkling wine, other voters drop in to the local party headquarters, bearing flowers, food and congratulations.

AfD has many faces. Among the supporters gathered here, there is a classics teacher, a pensioner, a businessman.

Birgit never used to vote, but this time cast her ballot for AfD

Most of those who voted for the nationalist party were manual workers or unemployed. More men than women. But there was significant support too from higher earners from the professional classes.

They used to vote conservative, Social Democrat, Left party or Green. AfD drew an estimated million voters away from Angela Merkel's CDU.

Or, like Birgit, a cheerful blonde woman who looks to be in her 60s, they used not to vote at all.

She explains what drew her to AfD.

"The old people don't dare leave the house after six o'clock," she says. "I live in such a beautiful place but when I open the door, the first thing I see is headscarves and then I go to the tram and I see the groups of young men."

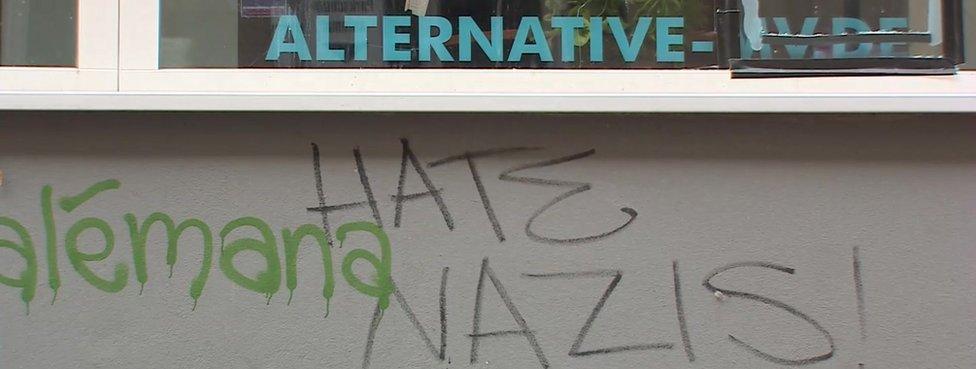

Opponents accuse AfD of being Nazis, and its headquarters in Schwerin has been attacked by protesters

The people in this room say they're fearful. Worried about "Islamisation" and terrorism.

They're saddened by what they see as the erosion of traditional family values. And they're angry. Their fury is directed at the mainstream political parties which, they feel, don't care about them. But the main force of their ire is directed at Angela Merkel and her decision to open Germany's doors to a million migrants.

They nod in agreement as Florian, a freelancer who tells me he works in the shoe industry, says: "The refugees come here but they don't plan to ever go back to their countries when the war is over. All along they planned to stay and replace the local population. More and more people are realising that."

Post-war politics of Germany: A history of division and unity

Support for AfD is particularly strong here in eastern Germany. This is the region of Mecklenburg Vorpommern. It's home to Mrs Merkel's constituency and it's also where almost 20% of voters chose AfD.

No-one's entirely sure why.

A fear, perhaps, of further change after a painful economic recovery from reunification, or maybe a reaction to what are perceived as the Western forces behind globalisation.

What is clear is that most of those who voted AfD were attracted by its insistence that Islam does not belong in Germany and its fierce opposition to Mrs Merkel's refugee policy, even though overall far fewer migrants were settled in this part of Germany than elsewhere.

Wolfgang, an earnest chap who looks anxious behind his spectacles, says that those who draw comparisons between the party and Hitler's Nazis are wrong. What are his reasons for voting AfD?

"I was a dissident in East Germany and I experienced the methods of a totalitarian state, propaganda and I now see how the mainstream parties use that kind of propaganda."

Painful reminders, violent division.

Outside on the cobbled street, the shattered window of the headquarters is a shock in the otherwise picturesque town centre. Someone has scrawled "hate nazis" on the building.

Not far away, low autumn sunlight ripples across the lake in front of the splendid façade of Schwerin castle.

AfD has already tasted power - it has seats in regional parliaments, including the Landtag that sits in this magnificent schloss. The party has already split, here at local level and on the national stage too, with moderates including party leader Frauke Petry walking away in disgust.

Not Leif Erik Holm. The well-dressed former radio DJ is one of the party's new MPs.

Mr Holm actually stood directly against Mrs Merkel. He didn't oust her, of course, but Germany's complicated voting system, which ensures parties are proportionately represented in the Bundestag, means he now has a seat in the Bundestag too.

He worries about the growth of Islam in Germany. The party's first act, he tells me, will be to demand an enquiry into Mrs Merkel's refugee policy.

AfD's Leif Erik Holm will demand an enquiry into Germany's refugee policy

"We have impact through publicity. We can't change laws because the other parties will boycott us - though they'll often use our ideas later, so yes we are important because voters discuss our policies," he says.

That may be a problem for the political powerhouse of Europe. AfD wants out of the euro currency. It'll voice boisterous opposition to any plans for deeper EU integration.

Its success indicates that the populism that has swept through Europe in recent years has taken root here. Germans have tended to identify as European first, German second. But for the very first time, a significant proportion of voters support a party which wants to claw back powers from Brussels and regain national sovereignty.

And it speaks to supporters of all ages, including younger voters, like Martin. Aged 28, he was drawn to the party when it first emerged as an anti-euro movement a few years ago. For him, a German withdrawal from the EU is not unthinkable. He worries about the financial implications of the union. But AfD, he says, also addresses widespread concerns about immigration.

"It's normal that if you have a lot of young men coming from other countries searching here for their luck and they see 'Oh my God, it's not so easy to get money or get a woman or whatever' - they start trouble."

Nick, a handsome blonde lad who's just 15, agrees with him. He can't vote yet but he's a member of the young AfD here.

"I support AfD because it's the future of my friends, me of course, my friends, my schoolmates. It will be a dark future if nothing really happens."

Fear of the future. Nostalgia for a country some fear lost. They are in the minority. But they are voices that will not be ignored.

- Published25 September 2017

- Published24 September 2017

- Published25 September 2017

- Published11 February 2020

- Published22 September 2017

- Published23 September 2017