Slobodan Praljak: How did he smuggle poison into Hague court?

- Published

Slobodan Praljak drank a small vial of liquid after his prison sentence was upheld

An investigation has been opened to try to find out how a war criminal was able to get hold of deadly poison while in a UN detention facility and smuggle it into what was supposed to be a secure courtroom.

Slobodan Praljak died on Wednesday after drinking the liquid - seconds after being told his 20-year sentence for crimes against humanity committed during the 1990s Balkan conflict had been upheld.

It was the last ever hearing before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) ceases to exist next month.

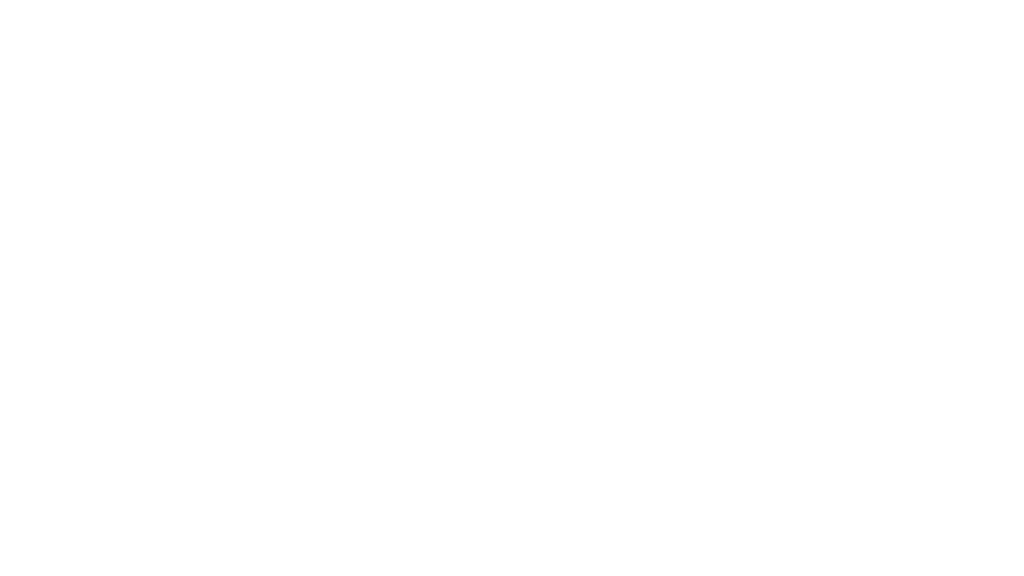

Praljak would probably have been driven to court from the ICTY detention unit. Even if he was frisked before entering the courtroom, it is not inconceivable he could have passed off the bottle or vial as medicine or other innocuous substance.

So the vital question for the investigators is how did he get hold of the lethal substance?

The court's detention unit is nestled in the sand dunes inside a Dutch prison complex in the Scheveningen neighbourhood. It takes approximately 10 minutes to travel between this building and the court.

Locals have nicknamed it "The Hague Hilton" on account of its relatively comfortable regime.

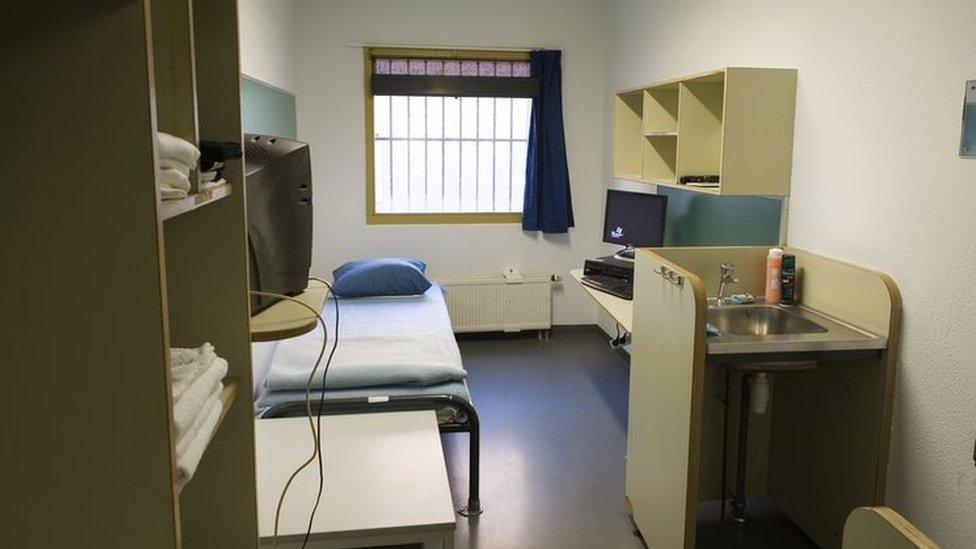

A standard cell of the detention unit in the Scheveningen neighbourhood

Detainees are only locked up in their cells at night. During the day they are free to move around and socialise.

Their daily schedule includes going outside for fresh air, exercise, occupational therapy and spiritual guidance. They have access sports and recreation facilities including pool and table football.

Visits are mostly supervised. There are conjugal rooms inside the unit - but security guards do not go in.

Defence lawyer Nick Kaufman described to the BBC security procedures at the ICTY detention unit.

"You go through main entrance. Anything you want to take. Personal items are deposited. Liquids, perfumes are visually examined but not chemically analysed.

"Then they're logged and one day a week those items are taken to the inmate by a security official. In theory, if a liquid was delivered there should be a record of that," the lawyer said.

According to the ICTY's website, "the physical and emotional welfare of detainees is of paramount importance".

Inmates are provided with general medical care and there are emergency services on site, which is considered especially important given the average age of inmates is 59.

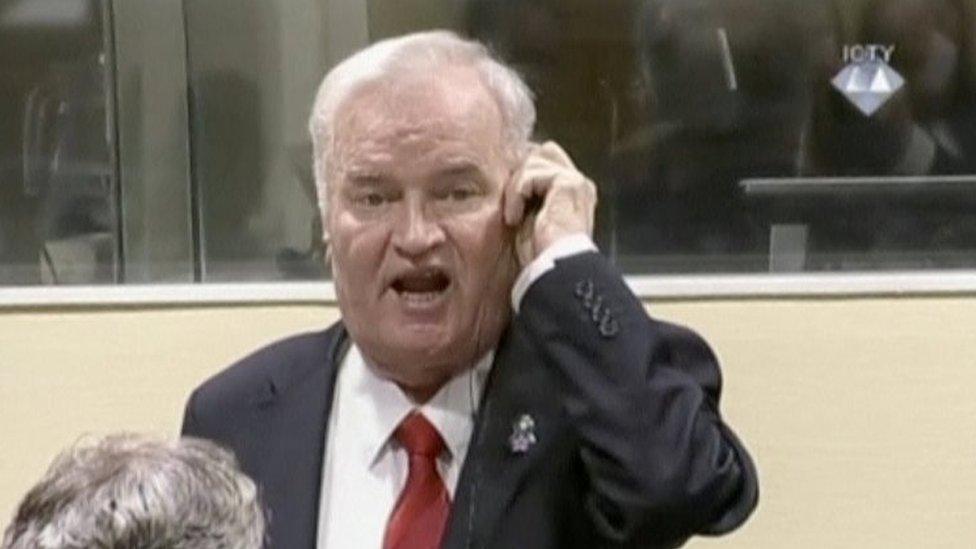

Mladic was this month jailed for life for genocide and other atrocities during the Bosnian war

Some suspects' health actually improves during their incarceration.

Ratko Mladic - recently sentenced to life for genocide and other crimes - famously credited the court's doctors with saving him when he arrived in The Hague with "one foot in the grave".

Mladic's lawyer Peter Robinson told the BBC: "I go to the detention unit every day during the trial. I'm totally perplexed as to how someone got this liquid in to him.

"We go through two security checks when we visit detainees. Two metal detectors. You can't bring drinks, not even a bottle of water or Coke. Everything is searched before you go in. I don't know how anyone could have smuggled in poison.

"I've only ever seen him with his family, in the room next door to us. But when his family came its private. There are no guards inside the room at the time, they stay outside the door. You can see your own doctors with special permission.

"I'm as shocked as everyone else. Totally baffled as to how someone can get a liquid in. It's not just sad for the court but also for his family."

There have been fatal lapses in the past.

Croatian Serb war crimes suspect Slavko Dokmanovic's body was found hanging behind the door of his cell in June 1998 while he was awaiting a verdict in his trial. He had used his tie and a wardrobe, despite being under supervision at the time.

In 2006, fellow Croatian Serb Milan Babic hung himself using his belt and a plastic bin-liner.

The most notable death in ICTY detention was that of former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, who died of natural causes in 2006.

An internal report found no evidence of poisoning or suicide (a request for medical treatment in Moscow had been denied by judges who said they saw no reason why Russian doctors could not treat him for high blood pressure and heart problems in the Netherlands).

With regards to this most recent and public of deaths, the Dutch authorities will look at who Praljack saw in the days and weeks before this final appearance, when there might have been an opportunity to hand over the lethal potion.

Before the war he worked as a television and film producer. He wrote his own ending in a scene no-one could have predicted, downing poison in front of an audience, his actions were broadcast live on the court cameras.

- Published16 November 2017

- Published18 March 2016

- Published16 January 2013