Macedonia: Why the row with Greece over the name runs so deep

- Published

Is Macedonia's name a cultural appropriation? Greece thinks so

Macedonia is rolling back on the trolling.

Its policy of "antiquisation" served for a decade as an epic act of nose-thumbing at its southern neighbour, Greece.

But last summer's change of government has brought a radically different approach - and hope of a solution to one of Europe's longest-enduring diplomatic disputes.

Since Macedonia declared its independence in 1991, Athens has refused to recognise its constitutional name.

Greece insists that only its own northern region should be called Macedonia - and it argues that the former Yugoslav republic's use of the name implies a territorial claim and cultural appropriation.

Protesters gathered in Greece against Macedonia's name last month

As a result, Athens blocked Macedonia's accession to Nato in 2008 - and would also veto its membership of the European Union if it refused to alter its name.

'High toll'

Seemingly deciding it might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb, Macedonia went on the offensive.

Airports, motorways and sports stadiums were renamed in honour of Alexander the Great and his father Philip - Greek heroes recast as Macedonian.

Then came the statues. Today, visitors to the capital, Skopje, could be forgiven for thinking they had stumbled into a "weeping angels" episode of Doctor Who.

A statue of Olympia, the mother of Alexander the Great, at a fountain in Skopje

Scores of statues loom from the ledges of bridges and peer down from plinths in the squares. Alexander is depicted both as a rampant warrior on a horse, and a babe in arms, cradled on his mother's knee.

Find out more:

Last June's change of government in Skopje has significantly changed the picture. The new administration, led by the Social Democrats, opposes antiquisation - on ground of taste as well as diplomacy. And it has already started to dismantle the policy.

Prime Minister Zoran Zaev has announced that Skopje's airport will no longer bear the name Alexander the Great. Nor will the motorway leading to Greece; that will now be known as Friendship Highway.

Most significantly, Macedonia has indicated a willingness to compromise on the issue of its name.

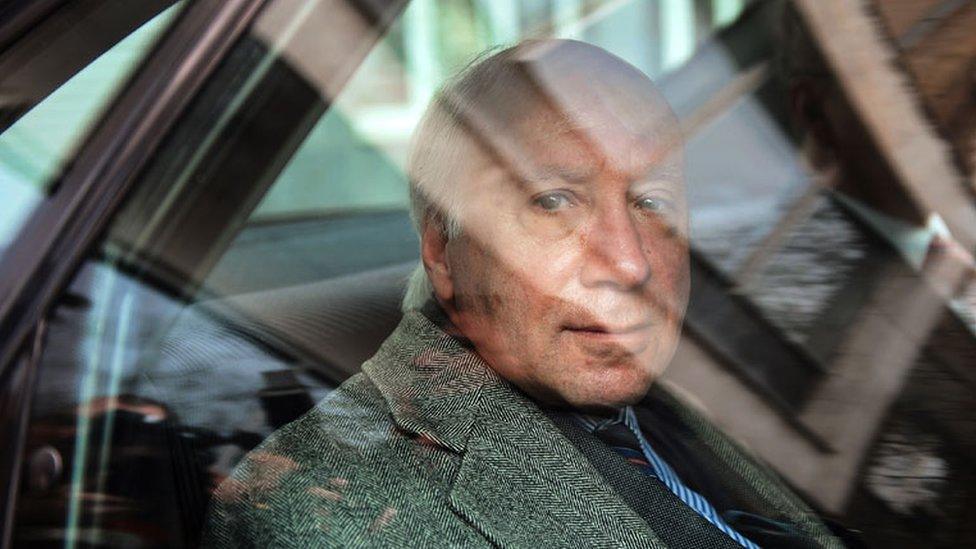

"The fact that our government has decided to rename the airport and the highway demonstrates that we are committed," says Defence Minister Radmila Sekerinska.

Macedonia's defence minister says she is optimistic about the negotiations

"It's not a show. We want to allow this country to free itself from an enormous burden that has taken a very high toll."

Cuts to core of identity

Athens has responded positively. Talks between the countries' foreign ministers were followed, last month, by a meeting between Mr Zaev and his Greek counterpart, Alexis Tsipras.

Matthew Nimetz, the United Nations mediator who has been working on the name dispute for a quarter of a century, believed that marked a breakthrough. He said the meeting was "positive and crucial" - and remained upbeat after visiting Athens and Skopje last week.

"I believe deeply that this is the right time to try to break through on this issue, solve it finally, move forward in the region with the two countries in friendship and cooperation," he said.

But there are people in both Macedonia and Greece who would prefer to see the process fail.

A demonstration in Athens over the weekend attracted a six-figure crowd. Their demand was clear: a new name for their neighbour should not include the word "Macedonia" at all.

"These are Slavs," said one woman in the crowd, pointing at a homemade map she was carrying.

"They are not Macedonians, we are Macedonians. Macedonia is Greek, no-one can take this name, no-one can use it."

Even Greek people who did not join the demonstration and support a solution to the dispute point out that the issue cuts to the core of their identity.

A native of Thessaloniki would call themselves "Macedonian" in the same way that someone from Burnley in the English county of Lancashire would identify as "Lancastrian".

So the name of the neighbouring state is, at best, awkward and, for some people, infuriating.

The M-word

The official Greek position has long been for a compound name, such as New Macedonia or Upper Macedonia.

But the opposition New Democracy party has seen an opportunity to use the dispute to gain political ground.

And a junior partner in the governing coalition, Independent Greeks, has made clear its opposition to any solution involving the "M" word.

George Tzogopoulos, an international relations expert at BESA Center, an Israeli think tank, says the demonstrators are misguided. But he is also gloomy about the outcome of the name negotiations.

"I don't understand why so many people are optimistic," he says.

"There are important differences between the two sides. Greece wants a name which would be used around the world, not just between the two countries. And that would require Skopje to change its constitution.

"The protesters' complaint that Macedonia shouldn't even be part of the name is completely unrealistic, but if you take into account that public opinion in Greece is completely misinformed, it's a normal reaction."

Alexander no more: Skopje's airport is to change its name

In Skopje, posters declaring "We Are Macedonia" have appeared on billboards opposite the National Assembly - insisting that the right to self-determination trumps Greek concerns.

But protest numbers have been very small. And analyst Sasho Ordanovski is convinced that the majority now have few objections to altering the country's name.

"The public in Macedonia is very realistic. People are sick and tired of not having progress in their lives.

"They are thinking and talking about this issue, thinking about Nato, security, the EU - being part of the world."

After 27 years of deadlock, now the question is whether the current political leaders have moved quickly enough.

The longer it takes to announce concrete name-change proposals, the more time it gives the opposition to organise on both sides of the border. And that could lead to many more years of name-calling.

- Published6 February 2018

- Published2 August 2017

- Published30 August 2014

- Published28 June 2023

- Published10 June 2024