Is this Angela Merkel's moment of reckoning?

- Published

Germany's Chancellor, Angela Merkel, is facing the fight of her political life, as a major row over the country's migration and refugee policy threatens to topple her from the post she has held since 2005.

Rarely do German politics produce such high drama.

One minister likened the twists and turns of the government crisis to an episode of Game of Thrones, while a German newspaper trembled: "The wolves are howling outside!" alongside a picture of the chancellery besieged by giant, Photoshopped beasts.

In such a febrile atmosphere, it's tempting to imagine an embattled Mrs Merkel inside, furiously striding the corridors and wondering out loud who will rid her of this turbulent Interior Minister, Horst Seehofer.

Mr Seehofer - leader of the Bavarian CSU party, in alliance in government with its sister party, Mrs Merkel's Christian Democrats - is relishing the opportunity to make the chancellor, and his old adversary, squirm.

Mrs Merkel has flatly rejected his plan to turn away migrants at the German border if they have registered elsewhere in the EU.

She believes such a unilateral act goes against European principles and intends to seek an EU-wide solution. Mr Seehofer - long an outspoken critic of the chancellor - says he will do it anyway.

Angela Merkel and Interior Minister Horst Seehofer are at loggerheads over refugees

Mrs Merkel is probably itching to sack him for such open rebellion. But she cannot do so without risking the CDU-CSU pact - and jeopardising her fragile coalition government.

Emergency talks have, as yet, failed to soothe an increasingly bitter row, which is being replicated, albeit in perhaps rather calmer tones, in plenty of other EU member states - between those who believe there is still a chance for Europe to rise unified to the migration challenge and the, largely populist, figures who are sick of waiting for it act.

But in Germany, there is a chance it could bring the government down. And Mrs Merkel would be, politically speaking, unlikely to emerge alive from the rubble.

Even as he continues to flex his Bavarian muscles, Mr Seehofer says that is not his intention. Most assume he is grandstanding ahead of the autumn's regional elections. The far-right, anti-migrant Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) has made gains in Bavaria.

In part, for Mr Seehofer, this is personal. He has reportedly never forgiven Mrs Merkel for her decision to allow asylum seekers trapped in Budapest passage to Germany, which, in effect, opened the country's doors to hundreds of thousands of people.

Most entered the country through Bavaria. Mr Seehofer, then the regional prime minister, is also reportedly still angry that he was not consulted - apparently Mrs Merkel did call him but he did not answer his mobile phone.

"I cannot work with this woman,"' he is reported to have told his party last week.

But plenty of others can. Angela Merkel has, it is said, the support of most of her party. She also has a public approval rating of 50% - for now.

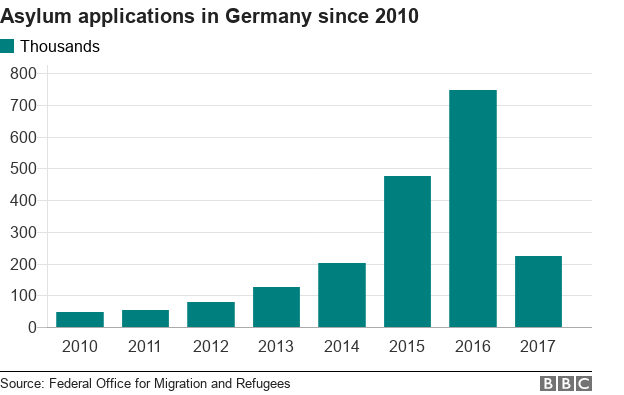

Because, despite falling migrant numbers - more than 720,000 people applied for asylum in 2016 compared with 200,000 last year - the issue remains centre stage.

This is largely due to AfD rhetoric and high-profile cases such as that of a failed Iraqi asylum seeker who has reportedly confessed to raping and killing a German teenager. Polls suggest most Germans want tighter border controls.

Mrs Merkel has failed to entirely quell public concerns with her oft-repeated assurance that 2015 was a one-off, or with a series of measures to tighten asylum law - making it easier to deport or deny entry to people coming from certain countries, for example - or with measures to ease integration.

So, if she cannot come back from the EU summit of leaders in just under a fortnight with some kind of plan or agreement, it will be open season on the German chancellor.

Horst Seehofer, keen to emphasise that he's not backing down, has agreed to wait to implement his plan for two weeks. Mrs Merkel has a little breathing space - but not for long.

Migrants on the Elisabet Bridge, in Budapest, in September 2015

Few expect a full-blown strategy to emerge - but it is not impossible that she will achieve something.

The details are not clear - but Mrs Merkel is already working on bilateral agreements that could see migrants being sent back to entry countries, presumably in return for funding.

She may be increasingly isolated among her European peers, many of whom make political capital at home by portraying her as the fiscal bully of the EU or by blaming her for the migrant crisis. But plenty of leaders share her resolve to strengthen external borders.

And countries such as Austria, Italy and Denmark, whose governments talk tough on migration, may seize the chance to press ahead with plans for, for example, detention centres outside the EU.

It is not inconceivable that Europe's shift to the right might aid Mrs Merkel now, just as did the closure of the so-called Balkans route - which she officially opposed - during the migrant crisis.

Of course, any victory or concession would be claimed by Mr Seehofer, who will argue it was he who pushed her into action.

He has little interest in watching the coalition fall apart. Few of its members do.

Fresh elections would be a horror show for the Social Democrats, who are languishing in the opinion polls. There would be little gain for the CSU in seeing the government fail. Already, this episode is inflicting injury - one weekend opinion poll suggests the coalition has lost its majority.

For now the drama is on hold. But this is no compromise.

And it leaves Mrs Merkel, already weakened by a poor showing in the September elections and damaged by her subsequent difficulty in forming a government, terribly wounded.

Angela Merkel was first sworn-in as chancellor in 2005

If those episodes represented the beginning of the end, this showdown is surely a staging post along the way. The German chancellor looks weary, worn down, out of energy.

The way she steadily works away at challenges does not have the shine, the catchiness of the populist rhetoric with which she is battling. She has barely responded publicly to several days of furious attacks from the CSU.

On Sunday evening, Mrs Merkel gathered with senior members of her party to watch Germany being beaten by Mexico in the group stage of the World Cup before discussing the government crisis.

The result is not the best of omens for the chancellor who famously relishes the drama, the manoeuvring on the pitch. Germany is watching her now. Half of its population is willing her to come out on the attack instead of appearing to stand helplessly at the goal, watching as the balls sail past.

- Published3 June 2019