What do European governments want from the EU Summit?

- Published

The EU summit on Thursday and Friday will discuss a number of pressing issues, including migration, economics, security and Brexit. But what do different countries want from the Brussels talks and where does Brexit stand in their priorities?

Germany: Jenny Hill, Berlin

It's tempting to imagine what Angela Merkel and Theresa May might say to one another in a private moment on the margins of the summit.

Both leaders, after all, face dissent and open rebellion from within their own ranks. And both are in a bind over borders.

But that's exactly why it's unlikely that the German chancellor will pay much attention to Brexit this week. She's far too busy trying to realise her long-promised European migration strategy - and saving her own political skin.

Her fragile government hangs precariously in the balance.

And it could fall apart if she can't return home with a solution strong enough to see off the rebellion from her interior minister - and coalition partner - who's threatening to unilaterally impose greater migration controls at the German border.

Theresa May and Angela Merkel both have domestic political problems

In such serious times here, the problem of Brexit seems far a less significant issue to preoccupied lawmakers.

But it's not that Germany isn't interested. Industry - in particular the mighty car manufacturing lobby - is beside itself at the thought of a no-deal Brexit.

In recent days, Joachim Lang, the director general of the Federation of German Industries, warned that the UK is "hurtling towards a disorderly Brexit". He added that only by remaining in the customs union and single market can the Irish border question be answered.

Most here want more clarity from Britain about how it perceives its future relationship with the EU, but Mrs May will encounter strong resistance to any proposals that even hint at the reinstatement of a border.

Mrs Merkel, on the other hand, whose experience was shaped by her own early life behind the Iron Curtain in East Germany, now finds herself in an EU openly discussing how and where to strengthen - or even reimpose - Europe's boundaries.

France: Lucy Williamson, Paris

France is going into this summit with two concerns uppermost in its mind.

The first is President Macron's beloved long-term project to tie the eurozone economies more closely together.

The German chancellor seems to have finally agreed in principle to a watered-down version of his plan, including a common budget for the eurozone and extra measures to help countries facing a recession, though the details are still vague. This summit will be a chance to put their ideas to the other EU countries.

The other issue dominating French minds is migration.

President Macron angered Italy earlier this month by saying it was "irresponsible" and "cynical" to refuse a rescue ship carrying illegal migrants. Italy accused France of hypocrisy, in return.

French President Emmanuel Macron sees eurozone reform and migration as two major challenges

The issue of how to relieve pressure on the front-line states in Europe's migrant crisis is divisive.

In 2015, the former French government promised to take 30,000 refugees from Greece and Italy, but a year later little more than 1,000 had arrived. And while the French government backs proposals for closed processing centres in front-line states, it does not want to see them on French territory.

With all this occupying French minds, there's little room to devote much attention to Brexit.

France has stuck pretty firmly to the EU line of "no cherry-picking", saying that freedom of goods, services and people cannot be separated.

But there are those in Paris who believe that appetite is growing to find wiggle room on frictionless goods trading, to protect French exporters to the UK. Though there's little indication that Paris will budge on the issue of a "passport" for the City of London and its financial services.

Spain: Guy Hedgecoe, Madrid

Spain's new prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, has made clear he intends to respect commitments his country has made to the EU and the European project in general.

But with a range of other issues occupying his agenda - particularly increasing numbers of migrants reaching Spanish shores and tensions in Catalonia - Brexit is not a main priority for the socialist premier.

However, he will not be able to ignore the impact the UK's exit could have on Gibraltar, whose British ownership Spain disputes.

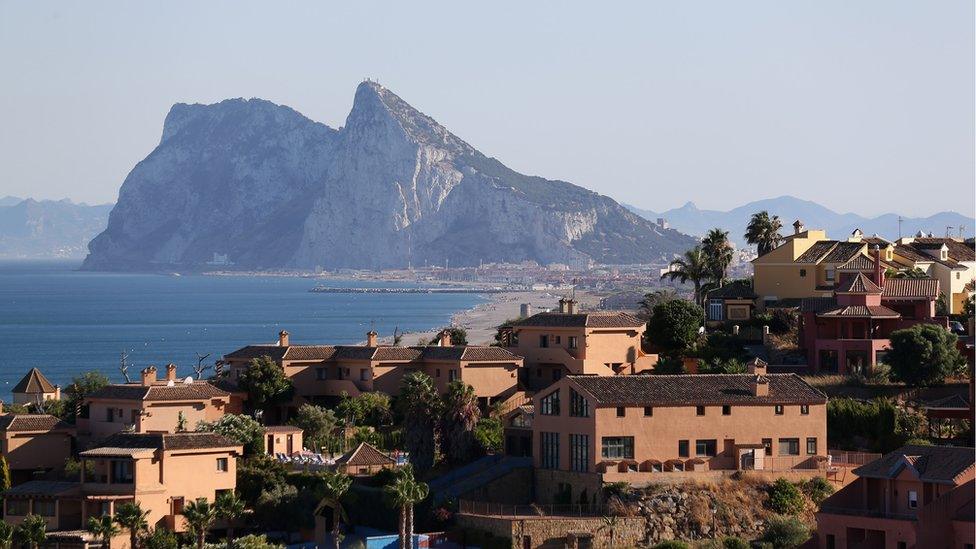

Gibraltar has long been a source of disagreement between Spain and the UK

At the summit, Mr Sánchez is expected to report on the status of recent negotiations between London and Madrid over Gibraltar's future status. Those talks, due to conclude by October, have focused on the possible shared use of the rock's airport and the exchange of tax information on citizens.

The EU has agreed that Spain can veto a Brexit accord if it is unhappy with the arrangements for Gibraltar.

The summit might offer clues as to whether or not Mr Sánchez intends to continue with the relatively tough line on Gibraltar pursued by the previous Spanish government. Either way, he will want to shore up support from his EU partners on the issue.

Italy: James Reynolds, Rome

To Italy's new populist government, Brexit is a rather distracting sideshow.

It wants to do business with a post-EU UK and it wants to ensure that the rights of Italian citizens living in the UK are protected. But beyond that, Italy's main preoccupation is migration across the Mediterranean.

In this respect, the country has two main objectives: to get EU countries to share the burden of sheltering those who've already reached this continent, and to prevent any more migrants from making the sea journey to Europe.

The Italian government wants to stop migrants from trying to cross the Mediterranean

In particular, Italy wants to get rid of the EU's Dublin Regulation, which calls for migrants to be screened in the first place in which they arrive. Italy believes that this places far too much pressure on front-line countries, including Spain and Greece.

But Italy may face resistance from fellow populist governments in central and eastern Europe, who do not want to take in any more migrants.

Italy's influential Interior Minister, Matteo Salvini, also wants the EU to accept an Italian-Libyan plan announced on 25 June to set up migrant holding centres on Libya's southern borders.

In theory, migrants from Africa would be directed to these centres, and prevented from making the journey across the Mediterranean.

Hungary: Nick Thorpe, Budapest

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban goes into this European summit in confident, but cautious mood.

He feels he's winning the argument on migration, but he knows he hasn't won it yet. Brexit, for him, is already yesterday's story.

His arch-enemy, Angela Merkel, looks wounded. The new government in Rome shares his anti-immigrant rhetoric, as does the government in Vienna.

Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban's anti-migrant stance has proved divisive to EU leaders

He can count on Sebastian Kurz, the Austrian Chancellor, to beat the anti-migrant drum for the next six months, as Austria holds the rotating EU presidency.

His allies in Bavaria, Horst Seehofer's CSU, are on the warpath. And the other Visegrad countries are right behind him.

But Mr Orban is playing for time - he sees his real chance after next year's European parliamentary elections, when he counts on a much bigger role for populist parties like his own, and populist leaders like himself, in the running of the European Union.

In the meantime, he still has to face annoying distractions, like criticism in the European Parliament for his crackdown on human rights groups.

He'll be hoping the summit is over as quickly as possible, so he can get back to watching the football. He hasn't missed a match yet, he told Hungarian radio.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published27 June 2018

- Published18 June 2018

- Published6 April 2018

- Published17 June 2018

- Published24 June 2018

- Published20 June 2018