A Turkish headache for the West

- Published

Turkey matters to the West but the question now being asked in Washington and in several European capitals is "just how much?"

Some US commentators go even further, wondering if Turkey should rightly be described as a strategic ally of the United States at all.

Turkey is a prominent member of Nato. Its military bases are important for current US air operations in the Middle East.

It straddles a huge swathe of territory on Nato's eastern flank, at a time when Russia's resurgence means the Black Sea region is of growing strategic importance.

Turkey is also among the European Union's most important eastern neighbours. Its progress towards joining the EU may have badly stalled, not least due to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's growing authoritarianism.

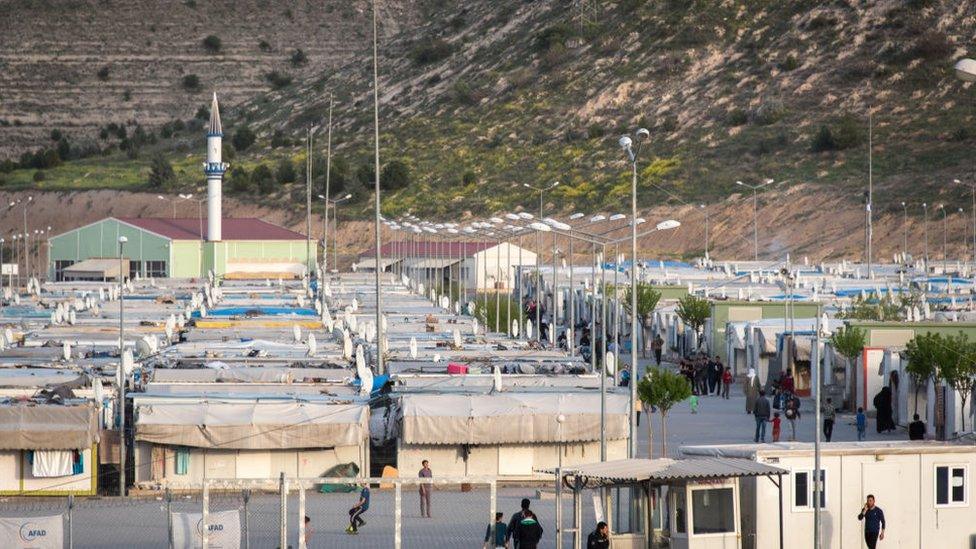

But Ankara remains a vital partner for Europe, playing a crucial role in helping to stem the flow of migrants westwards. Turkey itself is host to more than 3.5 million refugees from the fighting in neighbouring Syria.

The Nizip 2 refugee camp in Turkey houses Syrian refugees

President Erdogan is facing simultaneous economic and diplomatic crises that could further damage the foundations of his relationship with Washington and hence Nato.

The economic problems may be largely of his own making: a dash for growth, fuelled by major construction projects, all funded by loans.

But the row with the US - which focuses in part on the imprisonment of a US pastor, Andrew Brunson, accused by the Turks of activities hostile to the state - has become a battle of wills between President Erdogan on one side and President Donald Trump on the other.

And punitive US economic sanctions are doing further damage to Turkey's fragile economy.

So how bad could it get? Might Turkey's membership of Nato be called into question? Nato actually has no mechanism to expel an existing member: Ankara would have to decide that it wanted to leave.

During the Cold War, Turkey, with its huge armed forces, was always the anchor of Nato's eastern flank. In more recent times it has also been a significant contributor to the alliance's mission in Afghanistan.

The Turkish lira recently slumped against the dollar

But there have often been times when Turkey has been a problematic ally. Its frequent sparring with its historic enemy Greece in the Aegean has prompted tensions, but generally has been contained by their shared membership of Nato.

On occasions, Turkey has felt less than valued by its partners. They only agreed to deploy second-line aircraft to Turkey during Operation Desert Storm in 1990-91, when Ankara called for support to guard against retaliation by Saddam Hussein's regime.

In contrast, Turkey called upon Nato again early in the Syrian civil war when it sought, and received, allied anti-missile defence units, fearing that it might be targeted by Assad government forces.

But the Syrian War underscores the shift in Turkey's position. It has sought to become a major regional player, strongly backing rebel - and sometimes Islamist - groups on the ground, eager to overthrow the Assad regime.

Now with that policy in tatters, it is trying to secure its interests by working more closely with Moscow.

Turkey is seen to be building relations with Russia

Its relationship with the US was further complicated by the fact that Ankara resolutely opposed US support for Kurdish fighters in Syria. At times there was a real possibility of US and Turkish proxies coming to blows or worse, US and Turkish units coming under fire from each other.

Ankara's decision to purchase a Russian air defence system even as it seeks delivery of 100 F-35 jets, the latest warplane in Washington's arsenal, again underscores Turkey's unusual approach to alliance affairs.

But whatever Turkey's current tensions with Washington and by extension with Nato, it is hard to see a Russian link providing the same level of prestige, security guarantees or technical know-how.

What then of ties between Ankara and the EU? Could US-Turkish tensions be an opportunity for the Europeans?

Turkey is seeking to purchase F-35 warplanes from the US

On the one hand, many EU states are highly critical of authoritarianism and human rights abuses in Turkey. But the EU is intimately linked with Turkey's economy.

Many European banks have a significant exposure in the country and thus would be more than mere spectators if the Turkish lira collapses.

And for his part, there are clear signs - the recent release of two Greek soldiers and the local head of Amnesty International - that suggest President Erdogan does not want to have a full-blown crisis with the EU at the same time as he is at daggers-drawn with President Trump.

Turkey may have effectively been denied membership of the EU for the foreseeable future, but Mr Erdogan still has the migration card up his sleeve.

And, with a government offensive on the way in the Syrian province of Idlib, which borders Turkey, many more refugees could be on their way.

Greek soldiers Dimitris Kouklatzis and Aggelos Mitretodis were released from Turkish jails after 167 days of captivity

The EU is well aware that the migration deal it struck with Ankara has done much to reduce the flow of refugees into the union since 2016. Turkey received significant economic aid in return, and is unlikely to want to disrupt this relationship at a time of burgeoning crisis at home.

So in the short-term, relations between the EU and Turkey may improve as its relationship with Washington becomes more strained.

But in the longer term, Turkey's current direction of travel is, in some sense, away from the West.

This may be inevitable in a multi-polar world where Washington no longer has the regional prestige it once had. The Europeans may seek temporary advantage given Washington's problems.

In crude terms, Ankara has some strong cards to play when confronting Brussels. But fundamentally, Mr Erdogan is taking Turkey in a direction away from European values and liberal democracy. And that ultimately will condition his relationship with the EU.

- Published22 August 2023