Scallop row: French fishermen wary of UK deal

- Published

French and British fishing fleets have come to blows over when they can catch scallops

A deal has been reached to bring an end to the skirmishes between French and British fishermen in the Channel, but boat captains on the Normandy coast have vowed to fight on if any British boats come near their fishing grounds before October.

The agreement is yet to be signed and among those with most at stake are the two captains of La Rose Des Vents and Le Sachal'eo, whose dramatic collision with a Scottish trawler last week was caught on video.

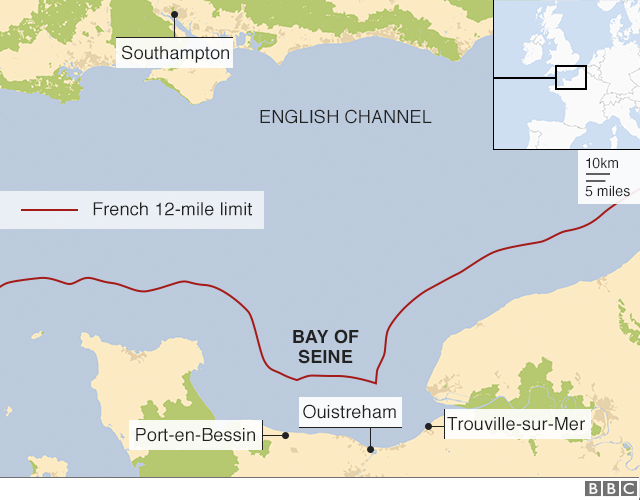

Anthony Quesnel, captain of La Rose Des Vents, returned to Ouistreham's empty dock on Wednesday after a night at sea and almost a tonne of mackerel, sole and plaice. But, in keeping with French rules, there were no scallops until the end of the breeding season at the start of October.

Like many fishermen here, he is adamant that British boats should abide by those same French rules when it comes to fishing for scallops - even though the UK government has in the past imposed no similar restrictions on its vessels.

French captain Anthony Quesnel says more clashes are bound to happen if British boats return to the scallop beds

Their refusal to do so justified the attack last week, he argues.

"Whatever happens," he told me, "I don't think the British will come back, because if they do another confrontation is inevitable. We'll defend our livelihood. I can't just stand by and watch."

Why the scallops skirmish began

For the past few years, a carefully constructed truce has kept the peace over this watery battlefield. The British agreed to ban their larger fishing vessels from the area until October, in return for extra fishing rights, and on the understanding that smaller British boats could fish there all year round.

But the number of smaller boats coming across the Channel has been growing and this year the French asked that all British boats stay away from the scallop fishing grounds until the catch could be shared.

Smaller British fishermen are already feeling hard done by because the vast majority of their EU fishing quotas go to larger British industrial fishing fleets, and many struggle to make a profit.

But scallops are not restricted by standard EU quotas.

Larger vessels have limits on the number of days they can fish for them but smaller boats do not - an important symbolic advantage.

Under the deal sketched out in London on Wednesday, the limits on bigger boats will remain. But the smaller British boats under 15m (50ft) will be subjected to the same rules and be given compensation for losses.

The terms still have to be finalised in Paris on Friday. But the two governments said that under a voluntary agreement all UK vessels would "respect the French closure period in the Baie de Seine".

Mr Quesnel said the conflict was the fault of the leaders, not the fishermen from either side.

The idea behind the French rule, he said, was "to let the scallops reproduce, not to fish it all out in three weeks and leave nothing behind. I believe the British boats all came this year to catch as much scallop as possible, because they know they won't have access to these after waters after [Brexit]".

A few kilometres away, in a tiny shed at Dives-sur-Mer, fish and mussels are being emptied straight from the boats on to a handful of well-scrubbed counters.

One of the fishermen here, Frank Tousch, remembers the clashes last week as "frightening". His tiny boat, Le Sachal'eo, was crushed between La Rose Des Vents and a 30m Scottish vessel, after he joined the demonstration at sea.

He shows us the cracks still running along the top of the wooden hull which he says will take him two weeks to repair.

"It pushed me from behind, up against La Rose Des Vents. Then pulled alongside to crush me," he said. "I was very scared; it was such a big boat. We were lucky that our hull was plastic so it bounced back into shape. Had it been all made of wood, it would have been crushed."

Fisherman Frank Tousch had his boat damaged in the "scallop wars" in late August

Frank agrees that the only way to solve the stand-off is for all British boats to observe the same restrictions as French fishermen.

The owner of La Rose Des Vents, Fabrice Huout, joins us at the market. Despite the attack on British vessels, he says, the anger is not personal.

"They're fishermen like us," he said.

I asked him whether he'd do the same in British waters if the situation were reversed. His response: "Why not, if we were allowed to?"

Back at Ouistreham, Anthony Quesnel is preparing to head to sea again, keeping an eye out for British fishing boats along the way.

Last week's attack was hastily organised, he told me, and many of the 300 local fishermen didn't get enough notice to join in.

Next time, he says, they will.

- Published29 August 2018

- Published29 August 2018

- Published28 August 2018