EU banks on last minute Brexit deal this autumn

- Published

Whether the EU can expect a deal with the UK ahead of its withdrawal will be determined in the next few months

Brussels is in full bustle again after the summer lull and Brexit is back - if not quite at the top - then certainly high up on diplomats' agendas.

This autumn is dubbed "The Final Push".

By mid-November "at the latest", according to the European Commission, a legally-binding withdrawal agreement - by which the UK leaves the EU - and an accompanying, though not legally binding, political declaration outlining how the EU and UK envisage their post-Brexit relationship, have to be signed off by both sides.

Considering the painful process Brexit negotiations have been to date, how likely is that to happen?

Let me first tell you that that there is a slow but spreading sense of panic EU-wide across business and industry. A no-deal scenario would be costly for Europe as well as for the UK

Those dependent on production lines, imports and exports fear the Brexit deal deadline won't be met this autumn thanks to a pernicious cocktail of turbulent UK domestic politics as well as the clashing demands of both sides in negotiations.

But step away from the storm and stress of inevitable posturing and business's understandable panicking, and a quiet word with EU politicians leaves you with a rather different impression.

Little appetite for total break-up

"The EU 27 (member states) have little appetite to make things difficult for the UK this autumn," one high level EU diplomat told me. "They have little appetite for broken relations with the UK. They want a deal."

Of course. Firstly, because a no-deal scenario would cost European businesses dearly, at least in the short-term as outlined above, and secondly - and even more importantly in the minds of EU politicians - because they look around at the volatile geopolitical situation worldwide and want to keep their UK friends close.

The government knows this, which is why you regularly hear government sources insisting that EU countries are on the verge of breaking ranks with the European Commission, because they are supposedly so "fed up" with the commission being "too wedded to EU rules and regulations".

These sources claim that EU leaders will instead now insist on more creative, political solutions (read: Theresa May's Chequers agreement) to bind the EU and the UK together harmoniously after Brexit.

A number of these sources suggest the dawn of this EU Brexit epiphany could be in a couple of weeks at an informal summit of EU leaders in Salzburg.

Except I'll eat my lederhosen if that actually comes to pass.

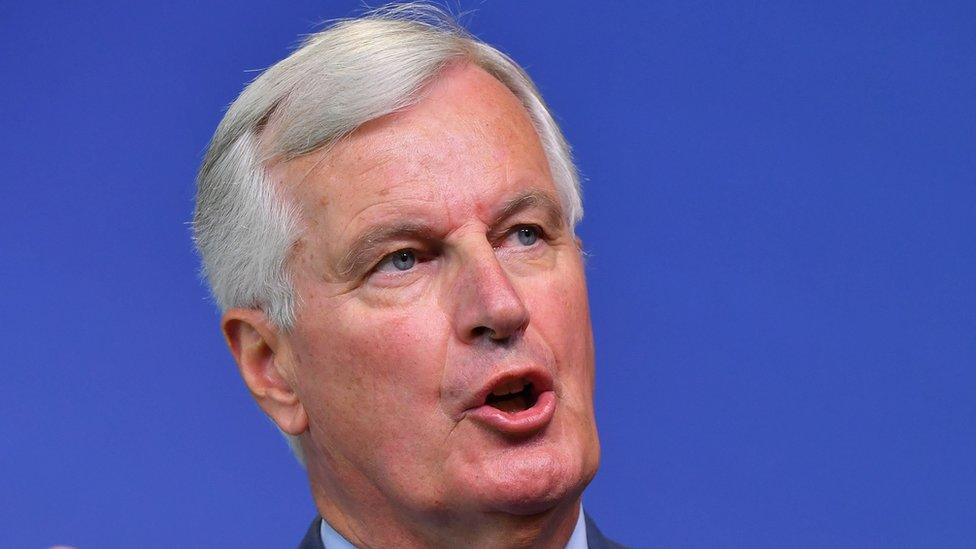

Some EU member states are said to be concerned over Michel Barnier's "inflexibility"

None of my background chats with European diplomats, politicians and civil servants suggest that this will be the case.

Sure, a number of European countries regularly grumble about the European Commission's Michel Barnier, the man tasked with negotiating Brexit on behalf of the EU.

I've heard him described as bossy, controlling and arrogant.

Some member states are irritated with his seemingly inflexible stance in Brexit negotiations over specific issues. Luxembourg felt that about financial services, for example.

But it would probably take a coup by 10 or more EU countries to overthrow Mr Barnier and most tellingly of all, there are no complaints from the Big Two: Germany and France.

Mr Barnier is far from alone in Europe in rejecting large chunks of the Chequers Plan as unworkable.

Labour's Stephen Kinnock said Mr Barnier described the Chequers plan as "mort" (which means dead in French)

This was already the case before the summer, but as I wrote at the time in this blog, the EU wanted to tread carefully to avoid further damaging Theresa May's authority just as she had finally produced what the EU had long been asking for - a clear British position - and when she was already in such political difficulty at home over Brexit.

Stopping the Eurosceptics

Europe's summertime whispers have now turned into loud voices.

Even German business leaders - the very individuals the government hoped would put pressure on Brussels to bend some rules to accommodate the UK - appealed at the weekend for EU politicians not to give in to the Chequers Plan calling for the UK to remain a member of the single market for goods but not of services or people.

Business leaders have agreed with Michel Barnier that "unravelling" the single market "just" to do business with the UK post-Brexit makes little long-term economic sense.

Europeans also have a political argument against what are seen as the "cherry-picking" proposals in Chequers.

"If the UK got all those Chequers concessions out of us by leaving the club, I wouldn't like to defend our position to Le Pen of France, Salvini in Italy or Germany's AfD," one EU diplomat told me.

"They'd start banging on again about life being better outside the EU. Forget it. We won't do that to ourselves."

Which is why Mr Barnier announced that Brexit negotiations are not centring on Chequers this autumn but rather exploring "common ground" between Chequers and EU guidelines.

"In the end this autumn, we just need to scrape through with the completed withdrawal bill and with sketchy outlines of a future relationship that everyone can live with," one high-level EU source told me.

A burning hot political potato

Theresa May is juggling dissent both at home and abroad for her Brexit plans

With UK politics so volatile, no-one in Brussels is 100% sure what these autumn months hold but the guess of the town is that Brexit negotiations will go to the wire.

Many here believe that would suit Theresa May.

The main sticking point to completing the withdrawal agreement remains the so-called backstop on the Irish border - ensuring that, whatever happens in the EU and UK's future relationship, no new hard border would be built between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

It's a burning hot political potato for the prime minister, as is finalising a declaration on the EU-UK future relationship - will it herald a United Kingdom that has taken back control or usher in a Brexit in Name Only?

With so many political opponents circling back in the UK, Brussels thinks Mrs May might choose to present parliament with a final hour, take-it-or-leave-it-and-face-no-deal-chaos agreement, produced after an all-nighter at a special Brexit summit in November.

"We'll then be happy to say anything that will help her at home," one political source here told me. "We'll say she's the toughest negotiator we've ever come across, if that helps."

In the meantime, as tension and uncertainty mount, the commission worries about keeping jumpier EU governments and businesses from agreeing bilateral so-called no-deal deals with the UK in specific sectors.

These are plans to work together bilaterally in the case of a no-deal scenario between the UK and the EU as a whole.

This summer may have been a scorcher but the autumn months promise to be far more blistering - in Brexit terms at least.

- Published5 September 2018

- Published5 September 2018

- Published4 September 2018

- Published4 September 2018

- Published5 September 2018

- Published23 August 2018

- Published7 July 2018