Switzerland considers tighter rules on sustainable 'fair food'

- Published

Local, high-quality food is already popular - but will the Swiss pay more for ethical farming?

Swiss voters are casting their ballots in not one, but two votes which campaigners say will promote ethical and sustainable food.

The votes follow scandals in the last few years over horse meat in lasagne and the destruction of rain forests to make way for palm oil and cattle ranching.

And they reflect growing consumer interest - not just in Switzerland but across Europe - in where food comes from and how it is produced.

Why two votes, and what's the difference?

Switzerland's system of direct democracy means campaigners simply have to gather 100,000 signatures to ensure a nationwide vote on a political issue.

The first proposal, called "fair food", wants more government support for sustainable, animal friendly products - and more detailed labelling so consumers know what they are getting.

It also calls for a crackdown on food waste, and for imports to meet Swiss standards on workers' conditions, environmental safety, and animal welfare.

This would mean Swiss inspectors checking foreign food producers for compliance.

The second, called "food sovereignty" goes even further, calling for much greater state support for local family farms, for higher tariffs on food imports, and for foreign produce that does not meet Swiss standards to be banned.

What do farmers say?

Many Swiss farmers support the proposals.

The price of milk has been falling, and an average of 1,000 Swiss farms a year are closing, many of them traditional alpine dairy farms.

Kilian Baumann, who has switched to organic beef on the farm that has been in his family for over a century, believes the future of agriculture lies in local family farming.

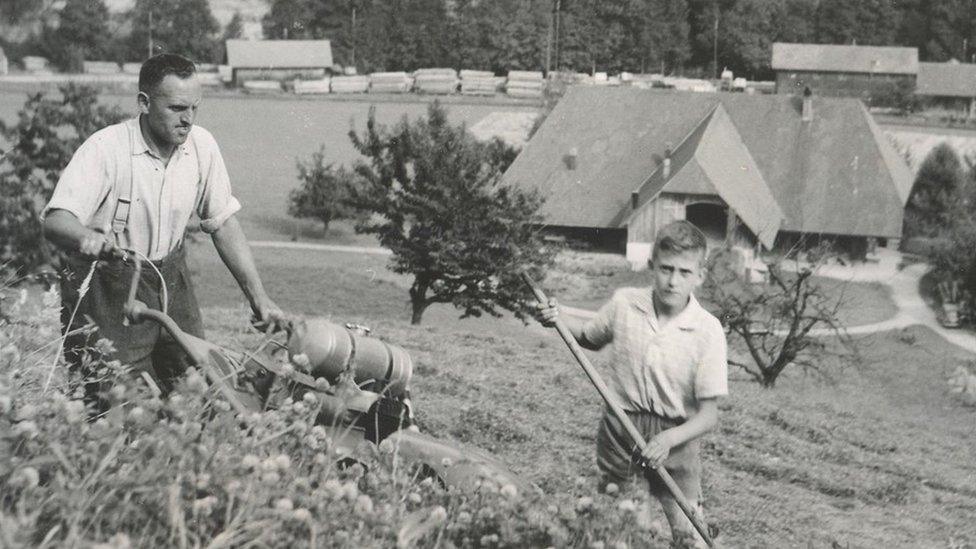

Kilian Baumann is one of those who has switched to organic farming

"I think things need to change in the food industry, we are making too many mistakes, in sustainability and with animal welfare," he says.

Ulrike Minkner, who has also abandoned dairy for organic beef, agrees. "We're not against trade," she says.

"This is about defending good food and good standards in Switzerland and abroad."

Other farmers are sceptical.

Switzerland already has high environmental and animal welfare laws. Member of parliament for the right-wing Swiss People's Party Marcel Dettling - who is also a farmer - thinks the proposals could actually be damaging.

"We farmers will lose. These proposals will force Switzerland's environmental standards on to foreign producers," he says. "So in the long run, we will lose our unique selling point: organic, environmentally sustainable produce, and we will create more competition from abroad."

What about consumers?

Again, opinions are divided.

The market share for organic "fair" produce is growing in Switzerland, where around 10% of all farms, or 14% of farmland, is now organic.

Many consumers say they want more diversity in organic produce, and more information about the food they buy. And not just in supermarkets - but in restaurants, where the origin and production conditions of food can be hard to discover.

Surveys show consumers are prepared to pay up to 20% more for local, organic meat, but that does not mean cost is not a concern.

Switzerland's biggest retailers have warned that approving the measures on fair food and food sustainability will inevitably lead to higher prices - in a country where food is already very expensive.

So what is going to happen?

First opinion polls gave both proposals support of 70% or more. But advice from the government is that some of the measures are unnecessary. They say animal welfare which is already strictly controlled, and other measures - such as setting Swiss standards for foreign food producers - are unenforceable.

That is having an effect on public opinion.

Concerns about cost are also a factor, and the latest polls show "yes" and "no" voters are neck-and-neck.

If voters do say yes, the government will have to implement measures which would give Switzerland the most rigorous food standards in Europe and might, if tariffs on foreign imports are implemented, put it in violation of its international trade agreements.

If voters say no, there will be relief from retailers and politicians.

But that is likely to be temporary: plans for future votes on food standards are already in the pipeline.

- Published8 December 2017

- Published19 July 2017

- Published17 May 2017

- Published12 April 2018

- Published16 May 2018

- Published24 January 2018

- Published18 August 2014