Russia cyber-plots: Dutch defend decision not to arrest suspects

- Published

The BBC's Gordon Corera looks at why the Russian cyber plot sting was surprising

The Dutch government has defended a decision not to detain four Russians accused of an attempted cyber-attack on the global chemical weapons watchdog in The Hague.

The suspected Russian agents were sent home as it was not a criminal inquiry, Prime Minister Mark Rutte said.

The US and UK have joined the Netherlands in blaming Russian spies for a series of cyber-plots worldwide.

Russia has complained of a "stage-managed propaganda campaign".

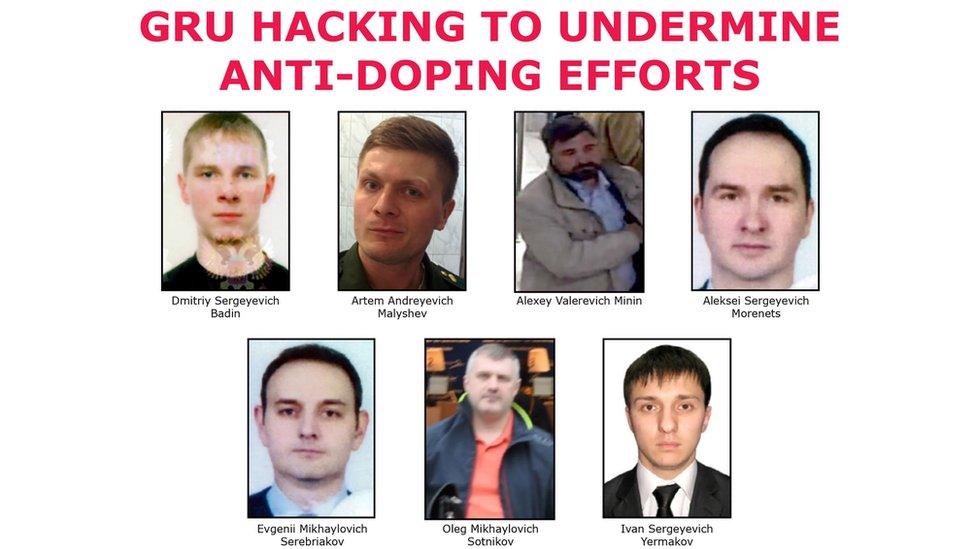

The decision in April not to prosecute the suspects starkly contrasted with a US announcement on Thursday to level charges against the four, as well as three other alleged members of Russia's GRU military intelligence agency.

Reports from Moscow on Friday suggested the Dutch ambassador had been summoned by Russia.

What is Russia accused of?

The Netherlands said it had caught four agents of Russia's GRU military intelligence red-handed in The Hague in April as they tried to hack the wifi network of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. The OPCW was investigating a chemical attack on Syria and a nerve agent attack on Sergei Skripal - a Russian ex-spy in the UK

One of the four agents, the Dutch said, had been in Malaysia targeting the investigation into the MH17 plane, shot down over eastern Ukraine

The US laid charges against seven agents for targeting its anti-doping agency, football's governing body Fifa and US nuclear energy company Westinghouse; of the seven charged, four were the men expelled from the Netherlands, while the other three were among those charged in July with hacking Democratic officials during the 2016 US elections

Canada said "with high confidence" that Russia was behind breaches at its centre for ethics in sports and at the Montreal-based World Anti-Doping Agency

The UK accused the GRU of four high-profile cyber-attacks, whose targets included firms in Russia and Ukraine; the US Democratic Party; and a small TV network in the UK

Read more: Transparency - the tool to counter Russia

'Spy mania'

By Steven Rosenberg, BBC Moscow correspondent

It's become a familiar pattern.

The West accuses Moscow of violating international law and provides evidence; Moscow denies it and derides the claims.

The military hackers story is no different. Russian officials and pro-Kremlin media have brushed aside Western claims of GRU cyber attacks with one phrase: "spy mania".

The Izvestia newspaper claimed "the virus of spy mania had once again infected the West".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Government newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta maintained the accusations of Russian military intelligence hacking were "baseless".

Russia's foreign ministry has already dismissed "Western hysteria about all-mighty Russian cyber-spies".

The tone is brash, mocking and belligerent. The message to the West - between the lines - is that Russia cannot be pressured or isolated.

But existing sanctions against Russia are beginning to bite and the country's economic problems are mounting. If the latest claims about GRU hackers spark a fresh round of Western sanctions, Russia's economic difficulties will only increase.

Who were the suspects in The Hague?

The passports of all four suspects were seized by Dutch intelligence - this belonged to Alexei Morenets

The four men had flown into Amsterdam's Schiphol airport in April on diplomatic passports, hired a car and parked it at the Marriott hotel in The Hague, next to the OPCW office.

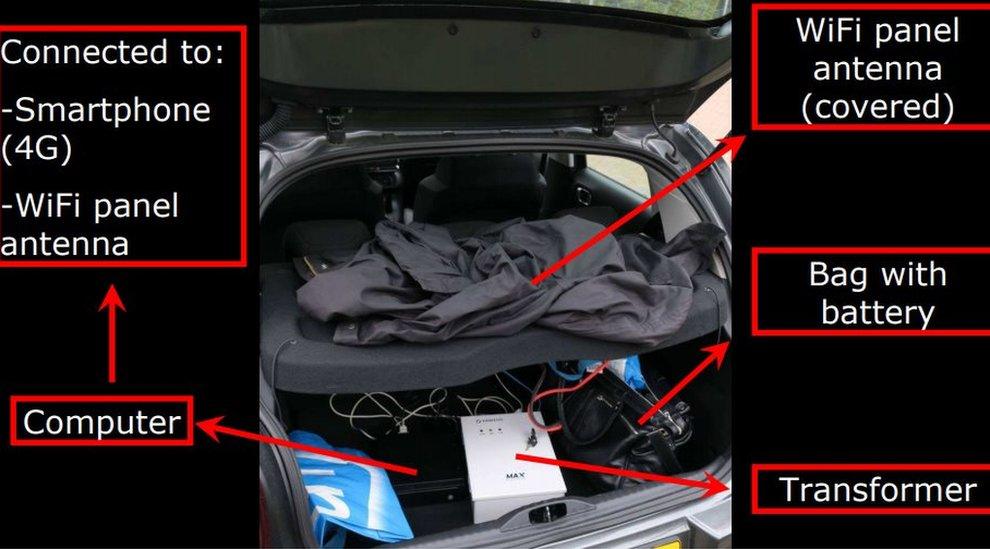

Their aim had been to intercept login details in the OPCW's wifi network from the boot of their car, said the head of the Dutch MIVD intelligence service, Maj-Gen Onno Eichelsheim.

He identified the men as hackers Alexei Morenets and Yevgeny Serebriakov, and support agents Oleg Sotnikov and Alexei Minin.

Officials said they were from the GRU's Unit 26165, which has also been known as APT 28. The UK's ambassador to the Netherlands, Peter Wilson, said the unit had "sent officers around the world to conduct brazen close access cyber-operations" - which involve hacking into wifi networks.

When the men were stopped, a large amount of technical equipment, mobile phones and a laptop were seized. But the men themselves were escorted to the airport and flown home rather than being arrested.

They had train tickets to travel on to the Swiss capital Berne and were planning to target a laboratory in Spiez where the OPCW analysed samples, Dutch officials said.

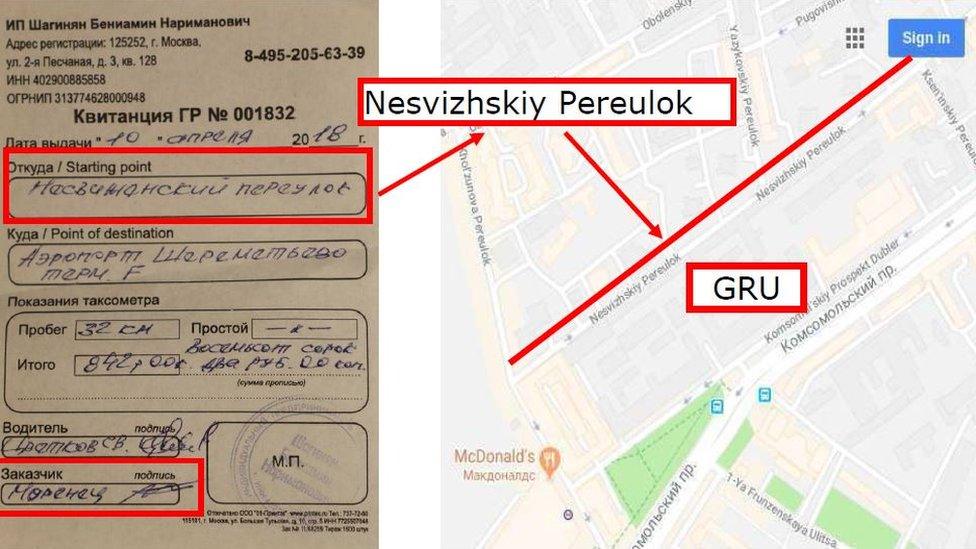

Among the mobile phones seized, one was found to have been activated near the GRU building in Moscow.

Also found was a receipt for a taxi journey from a street near the GRU to the airport. The taxi firm has confirmed to the BBC that the receipt is genuine.

In a separate development, investigative website Bellingcat alleged that a car owned by one of the four, Alexei Morenets, was registered to an address on Komsomolsky Prospekt in Moscow - home to GRU's 26165 military unit. It has found details of 305 individuals whose cars are registered to the same address on a vehicle database.

Why were the four sent home?

Even though the men were travelling on diplomatic passports, they could still have been arrested because they were not accredited diplomats in the Netherlands.

So questions have been asked about the decision to send the suspects home immediately, rather than detain them. Hours after the cyber-plot revelations, US justice officials levelled charges against the four suspects as well as three others.

Dutch intelligence named the four suspects who had travelled to the Netherlands on diplomatic passports in April

Asked on Dutch TV on Thursday night why the men had not been arrested, Maj-Gen Eichelsheim explained that it had been a counter-intelligence operation with the specific aim of gathering intelligence and keeping the Netherlands safe.

Political leaders agreed that the men had not been detained because it was an intelligence operation, rather than a criminal inquiry led by the police.

According to Dutch expert Willemijn Aerdts from Leiden university, the intelligence services have no powers of arrest or prosecution.

"If they had arrested them, they would have had to inform the police," she told the BBC.

"It might have been a difficult decision but it was probably a political thing as well. The defence minister would have known."

The FBI released this "wanted" poster, naming and picturing the seven men

"I don't want to describe this as 'letting them go'," said the head of Dutch military intelligence. "We disrupted an operation. That's how we do this type of operation."

His over-riding thought in reacting to the alleged cyber-plot had been "I'm not going to let this happen", he said.

What have we learned about the alleged cyber-plot?

The laptop seized from the suspects was found to have been used in Brazil, Switzerland and Malaysia, the Dutch officials said.

According to the UK ambassador to the Netherlands, the cyber-operation in Malaysia had targeted the attorney general's office and Malaysian police as well as the investigation into the MH17 crash, in which 298 people died.

Earlier this year Dutch-led international investigators concluded that the Buk missile which had brought the plane down had been transported by road from a Russian military base.

Data from the laptop showed it had also been used in the Swiss city of Lausanne and was linked to the hacking of a laptop belonging to World anti-doping agency Wada, which has exposed doping by Russian athletes.

- Published6 October 2018