World War One: Dublin's 'Haunting Soldier' marks centenary

- Published

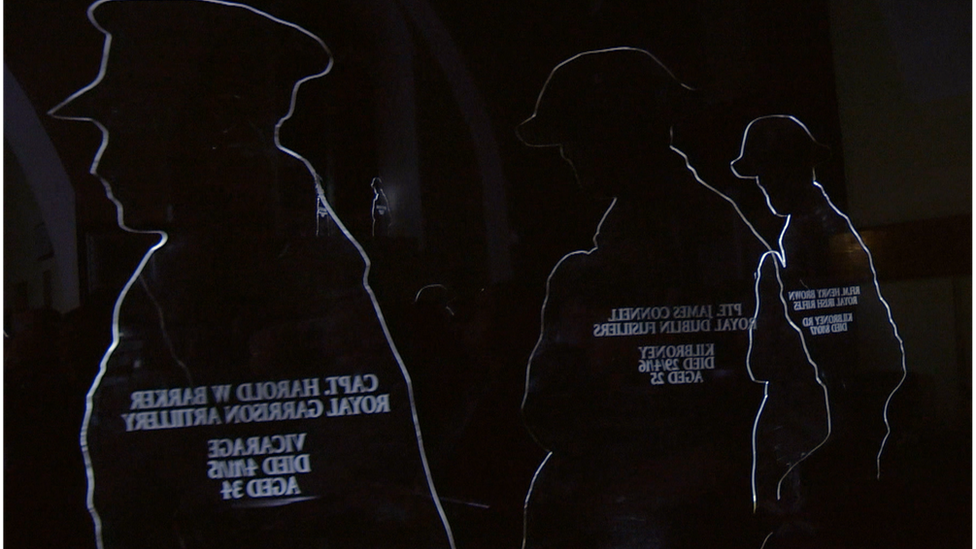

The 'Haunting Soldier' is made from scrap metal

A six-metre-tall soldier made of scrap metal has gone on show in Dublin to mark 100 years since the end of World War One.

The Haunting Soldier will dominate the entrance to St Stephen's Green park until the end of November.

It has been unveiled ahead of the centenary of the end of the war on Sunday.

The soldier was made in Dorset from scrap metal, including horse shoes, spanners and car jacks.

The sculpture was designed to evoke the fragility and suffering of those who survived the war and who returned home to an uncertain and difficult future.

The woman who commissioned the piece, Jo Oliver, said the Haunting Soldier commemorates all those who served in World War One.

"He is us. He is the common man, not linked to any race or politics and certainly not to the love of war," she added.

St Stephen's Green, at the top of Grafton Street in the centre of Dublin, has its own military history.

The archway at its entrance commemorates the British Army's Royal Dublin Fusiliers and it was where Irish revolutionary hero Countess Constance Markiewicz fought the British in the 1916 Easter Rising.

The 'Haunting Soldier' will stay in Ireland for a month before returning home to England

Among those present for the ceremonial unveiling was Kingsley Donaldson, a soldier and a brother of DUP MP Sir Jeffrey Donaldson.

He is the secretary of the Northern Ireland First World War Centenary Committee.

He said the sculpture is a "gentle way of reminding people who haven't been able to engage with the centenary and other contentious centenaries of this time".

"Here in St Stephen's Green because of its history, it's appropriate in that it allows us to think about what that war meant for individuals and their loved ones," he added.

At the ceremony, amid the occasionally falling autumn leaves, a choir and the Hothouse Flowers' lead vocalist, Liam Ó Maonlaoi, performed songs from that period and traditional airs - some a haunting reminder that 36,000 Irish soldiers died in the war and the survivors returned to a very different country turned upside down by Easter 1916.

Until the peace process it is unlikely that an event like the public display of the metal British soldier would have been possible here.

Stephen Drury's grand uncle, Joe Drury, an ambulance man, survived the war but the family later learned that he had gone on strike because of the 1916 leaders' executions.

"His Liverpudlian sergeant was a trade unionist and his attitude was 'one out, all out'."

"So, all the drivers went on strike but in the morning Joe had a change of heart and decided to go back to work because the men needed him.

"And they all went back to work. No official notice was taken of the strike, " Mr Drury said.

Among those present in the run-up to Sunday's centenary was the independent junior government minister, Kevin 'Boxer' Moran.

'Those who did not return'

He paid tribute to those who organised the event including Sabina Purcell who became interested in the Great War while researching her own family's involvement.

"I just wanted to bring the soldier over to remember the lives lost and those who did return home," she said.

"The soldier represents all the vulnerabilities of those who served in World War One from all the island of Ireland."

The soldier made of scrap metal perhaps symbolically suggests that human life in war is also all too disposable.

He will overlook St Stephen's Green for the next four weeks before returning to Dorset.

- Published3 November 2018

- Published4 November 2018