The digital activist taking politicians out of Madrid politics

- Published

Pablo Soto was once best known as a file-sharing software developer

Once, he faced down major music industry giants over the file-sharing software he created. Now, Pablo Soto wants to use his digital knowhow to reshape democracy.

He is in the left-wing coalition that beat traditional parties to take over Madrid's council in 2015.

Now, as Madrid's head of open government, Mr Soto has launched a platform where citizens dictate policies to city hall and choose what to spend taxes on.

"I don't think of myself as a politician," the councillor says. "But I am a political person."

"I want public participation to be the prime mechanism for reaching political decisions, with the role of politicians reduced to handling the lesser day-to-day stuff."

How file-sharing crusader became an activist

A decade ago Mr Soto was a twenty-something computer programmer who had designed a series of person-to-person (P2P) file-sharing applications used by 25 million people around the world.

Many of them used the software to share music files.

Mr Soto, who has muscular dystrophy and uses a wheelchair, was sued in 2008 by Warner, EMI, Sony and other entertainment industry giants for millions of euros in allegedly lost revenues - a sum he says he could not have dreamed of amassing.

He eventually won a drawn-out series of battles though Spain's courts that, he says, made him more politically aware and an activist for internet freedom and net neutrality.

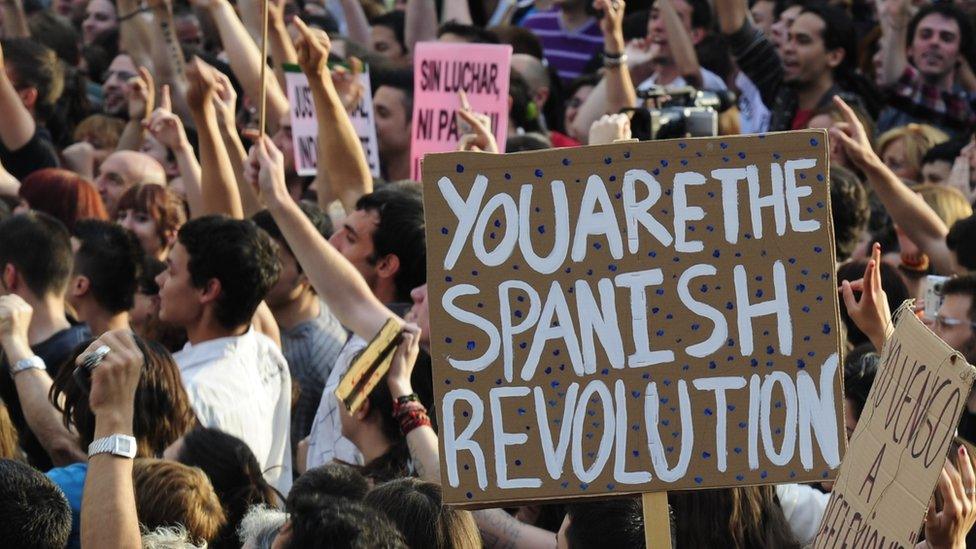

Pablo Soto was among thousands who joined 2011 protests against Spain's economic crisis and high jobless rate

He then joined the mass street protests against Spain's party politics that mimicked the Arab Spring revolts.

"The most political moment of my life was the night of 15 May 2011, when I decided to take my rucksack to Puerta del Sol in Madrid, even though there was a threat of the police clearing the square as the protest had been declared illegal.

"We challenged a whole system of representation in which a few people have 100% power of decision for years, without having to explain or allow citizens to participate."

From street protest to digital democracy

Mr Soto turned to technology to open up the decision-making process.

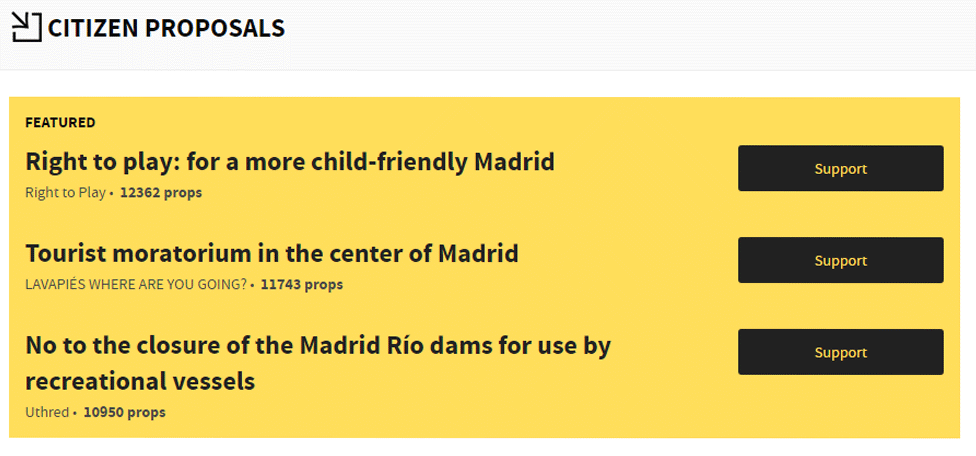

Decide Madrid is an online platform with 400,000 users in the Spanish capital. Any of them can propose an idea, which, if backed by 27,662 other users (1% of the city's adult population), goes to a referendum.

Mr Soto was elected to the Madrid council in 2015

"It is voted on by the people, not the council. The politicians cannot block it," Mr Soto says.

Other cities where left-wing coalitions swept to power in 2015 - including Barcelona and Valencia - have also set up participative systems to take collective decisions on public facilities – and on how to spend part of their budgets.

In Madrid's process, citizens can vote online or in person to decide how to allocate €100 million in spending - a significant part of the council's total investments every year.

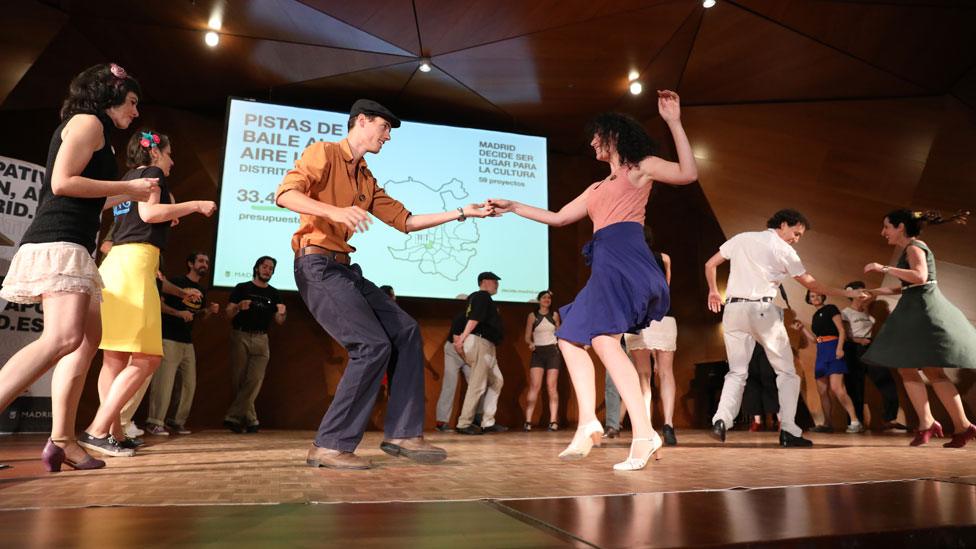

Swing dancers celebrate approval of their new outdoor dance floors

The software driving Madrid's participatory platform has been adopted by 100 government institutions in 33 countries, with Uruguay the first country to use the free software at a national level.

Critics of direct democracy warn that well-organised single-issue groups could hijack the debate, such as anti-vaccine campaigners in Italy. There are also concerns that minority groups might be crushed by the wheels of majority power.

But Mr Soto believes people can be trusted with political decisions.

He cites studies of direct democracy which suggest taxpayers may take greater care with public money than electioneering politicians. He also says Madrid citizens have shown solidarity with others, backing new homes for women victims of gender violence and day centres for Alzheimer's patients.

"Politicians have always sold us the idea that it is a contradiction to support something that doesn't benefit you. Our experience shows that the opposite is true."

What next for Pablo Soto?

This month Madrid plans to launch Mr Soto's most far-reaching reform yet - an "observatory" of 57 citizens selected at random to advise the city's 57 councillors.

Mr Soto explains that an algorithm will ensure that observatory members will be representative of Madrid's social diversity, with a one-year mandate and access to expert assistance to reach well-informed decisions.

A selection of the citizens' proposals (translated from Spanish) featured on the platform in early January

The concept was inspired by the ancient Athenian practice of choosing citizens to form governing committees, and by more recent examples where governments have asked the people to decide on single issues to break political deadlock.

In Australia, a "citizens' jury" was asked about the construction of a nuclear dump, external.

"The idea is as old as democracy itself," he says. "A group of people chosen at random - if they have the time and capacity to study the issues in depth - can take very representative decisions."

Mr Soto does not plan to stop at Madrid, and notes that his platform could now be used to connect people across the globe in joint decision-making.

"It does not make sense that the world is still organised along territorial lines, because the internet contradicts these geographical distances."

- Published7 July 2017

- Published20 January 2015

- Published5 December 2016

- Published12 December 2022

- Published3 October 2017