Debt misery hits students as dream turns sour in northern Cyprus

- Published

Northern Cyprus has attracted a big student community but many who come feel let down

"It's the survival of the fittest on this island," says Lovli, a student in her twenties from Nigeria.

Fighting back tears, Lovli describes how she left home to build a better life, leaving behind a husband and two small children whom she has not seen in more than two years.

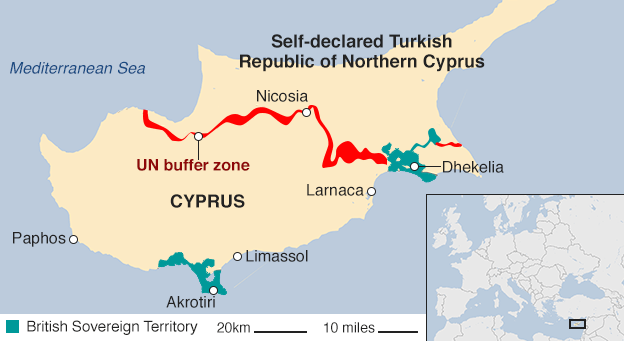

She is one of some 120,000 students in Turkish-controlled northern Cyprus, a self-declared republic recognised only by Turkey. That is a lot of students among a permanent population of not much more than 300,000.

Promise of cheap studies and work

Years of political and economic isolation have taken their toll, but a booming industry in higher education has lured students from developing counties with the promise of cheap tuition fees, palm-fringed beaches and a chance to work in Europe.

Before 2011 there were only six universities here. By the end of 2019 that figure is expected to top 30.

Lovli's life here has not lived up to the dream she was sold.

A Nigerian friend of her husband, working as an agent for universities in northern Cyprus, told her she could study here for only $1,500 (£1,150; €1,300) a year as well as find a job to help her family back home.

When she arrived, the meagre savings she had, which she thought would pay for the full amount of her fees, only covered the first instalment.

She would now need to earn $1,000 a month to cover all expenses including fees, but she can only get unregulated low-paid jobs like cleaning and cooking, and is working long hours seven days a week.

Absolutely nothing is left over to help her family back home, and she cannot afford a ticket back either.

For many people like her, Northern Cyprus was not really about education, but about a promise of a chance to work in Europe and forge a better life for her and her family. And that is not happening.

Loan sharks and prostitution

Lovli is not alone. There are many fellow Africans, and Asians too, who find themselves in dire straits.

A Zimbabwean pastor, who prefers to remain anonymous, says many of the students fall prey to loan sharks. When payback time comes, things "can get ugly... and police say they cannot intervene", he says.

A number of female students have told him they have been forced to pay back their debts "with sexual favours". He claims he saved one woman from a house where she had been kept for months and forced into prostitution.

"There were threats, shouting, verbal abuse. I think they expected me to run away but somehow I just stayed put and then I went in and took the girl out," the pastor said.

She is still on the island, as many students become "conditioned" to this kind of life, he says.

The border fence: No settlement has been reached despite years of negotiations

Territory under embargo

Cyprus has been divided since 1974, when Turkish troops invaded the north, in response to a military coup backed by nationalists ruling Greece at the time.

Since declaring independence in 1983, the north has been under international embargo, so it is propped up by Turkey and its currency, the lira.

The only way African and Asian students can come and go is by plane via Turkey. They are forbidden from crossing the so-called green line into the Greek side.

Then there is the risk that their degrees are seen as worthless.

As northern Cyprus is not recognised internationally, a degree from here not only has to be accredited by local licensing body Yodak, but by Turkish authorities too, for it to have any global appeal.

While some students might find themselves at an unaccredited establishment, Yodak director Akile Buke believes "the number is small".

She says inspections began only recently and improvements were demanded from 11 universities. Ms Buke wants local laws changed to prevent so many universities opening with minimal regulation.

Her opinion is shared by Necdet Osam, rector of Eastern Mediterranean University, established 40 years ago. "The new universities should be guided by the old ones and if they are not any good they should be closed," he said.

Universities with no international recognition

One of the universities that has lost its accreditation from Turkey is Akdeniz Karpaz, based in a high-rise glass building on the Turkish side of the divided capital, Nicosia.

It is part-owned by Turkish MP and businessman Ahmet Erbas, whose family also run a local hotel and casino and have a stake in northern Cyprus's only airport, Ercan.

He blames the loss of accreditation on the size of their campus rather than teaching quality, but says it has not affected the intake of foreign students who "don't care about it".

Turkish Cypriot minister Zeki Celer shares his office with a pet cat

Local labour minister Zeki Celer has launched a Facebook name-and-shame campaign targeting businesses that exploit foreign students and promises protection for those who report abuse.

But the changes are taking too long for the Zimbabwean pastor, who has a warning for any prospective student's family.

"If you're going to send your child here, make sure you have a solid financial plan. Don't send them thinking they're going to greener pastures."

- Published11 January 2019