Spain's 'stolen baby' finds out she was adopted

- Published

Inés Madrigal (centre) met other aggrieved families at the trial

The first person recognised by a Spanish court as one of the country's "stolen babies", who were snatched from their mothers during the Franco dictatorship, has found her biological family following a DNA test.

But Inés Madrigal also found that she wasn't stolen after all, but adopted.

A court had last year ruled that an elderly doctor stole her as a baby.

Thanks to a DNA database in the US, Ms Madrigal discovered a cousin, who put her in touch with biological siblings.

Ms Madrigal, 50, was a test case for the many infants taken illegally from their mothers. The mothers were told their children had died, but the children were given to other families to adopt, often with the help of the Catholic Church.

The practice began under Gen Francisco Franco and went on for up to 50 years, until the 1990s. No-one knows how many babies were stolen but victims' groups estimate that the number taken from their mothers could be as high as 300,000.

Ms Madrigal's revelation that her mother willingly gave her up for adoption has now prompted prosecutors to reconsider the case.

What Madrigal discovered

Last year, Inés Madrigal approached California-based genetic analysis company 23andMe and provided a sample of saliva. The company contacted her in January with news that she had a relative in Spain.

Through that relative, she managed to get in touch with her biological siblings. She found out that her biological mother had died in 2013 but that she had three brothers on her mother's side and an aunt.

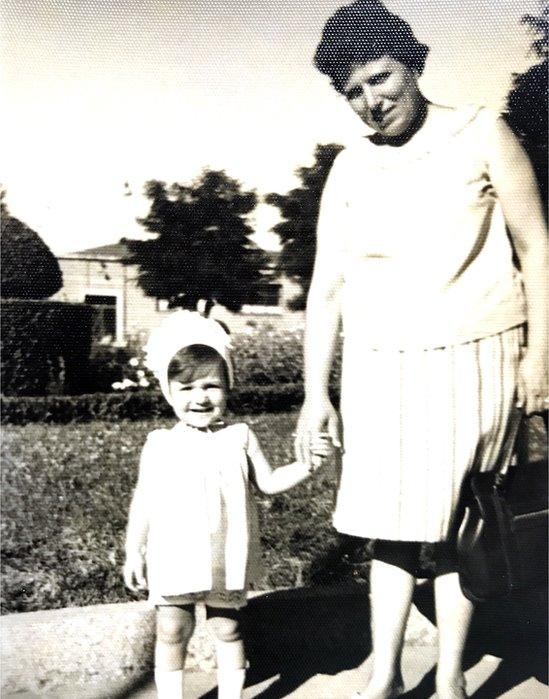

Inés's adoptive mother Inés Pérez (R) said she had been given the baby as a gift by Eduardo Vela

Their DNA matched and the brothers revealed their mother had told them they had a sibling whom she had volunteered for adoption. They also have a sister in the US, Spanish newspaper El Mundo reportd.

"For the first time, I have completed the puzzle that is my life," Ms Madrigal told reporters in Madrid.

El Mundo also reported that one of Ms Madrigal's brothers had sent her a Facebook message in 2015 because he was looking for the baby born in June 1969. She did not see the message until this year.

Why she thought she was a stolen baby

Ms Madrigal's adoptive mother, Inés Pérez, told her when she was 18 that she was adopted, and when the "stolen babies" scandal emerged she began looking into her own past.

The practice began in the late 1930s, when children were taken from families deemed "undesirable" - often because they were identified by the ruling fascists as Republicans.

Inés Madrigal approached a DNA testing website in the US in 2018

Mothers would be told their babies had died in childbirth, and their children would then be handed to couples with links to the regime, often with the help of the Catholic Church.

Inés Madrigal believed she had been abducted after she was born in 1969. Her adoptive mother told a judge before she died that Dr Eduardo Vela, a former gynaecologist, had given Ms Madrigal as a gift because she could not have children of her own.

Dr Vela initially admitted signing her birth certificate, stating that Ms Pérez and her husband were the biological parents, but when he went on trial in 2018 he said the signature was not his. His clinic closed in 1982.

What happens now?

Dr Vela was found by the court to have committed three crimes in relation to Ms Madrigal, including faking Inés Madrigal's records and handing over a child without the consent of its parents.

But he was acquitted after the court ruled that Ms Madrigal had waited too long to file a complaint. His acquittal prompted prosecutors to file an appeal to Spain's Supreme Court and that case is still pending.

Then this year Ms Madrigal told prosecutors that she had found her biological family, and prosecutors ordered their own DNA tests to check. They have now decided that the court's ruling that Dr Vela had stolen a baby should no longer be considered valid.

But the Supreme Court's case is still expected to go ahead, Spanish media reported, and that will help clarify how long the authorities have to prosecute those alleged to have taken part in the stolen babies scandal.

Find out more about Spain's stolen babies

Manoli Pagador told the BBC in 2011 how her baby son was taken away from her in 1971

- Published8 October 2018

- Published26 June 2018