Brexit: Dublin dismisses backstop pressure talk as 'codswallop'

- Published

EU chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier and Leo Varadkar in Brussels on 20 June

There is a weary sense of "here we go again" among Irish government officials dealing with Brexit about briefings coming from London that Dublin is under pressure from other EU members about the backstop to avoid a no-deal Brexit.

The backstop is the insurance policy in the withdrawal agreement between the United Kingdom and European Union, designed to ensure that there is no hard border on the island of Ireland.

Both sides say they hope it never has to come into effect and that it will become redundant because of a wider trade deal.

While Irish sources describe Tuesday's phone call between Leo Varadkar and Boris Johnson as "warm and friendly" on "both a personal and a political level", that description is bound to raise an eyebrow given the widening gap between the two capitals.

Especially after what the prime minister has been saying about the need to bin the backstop as a precondition to get into Brexit negotiations and to avoid a no-deal exit.

Irish sources insist Dublin has not come under any EU pressure to relent on the backstop, with one source describing as "codswallop" suggestions otherwise.

Another says this isn't the first time there have been inaccurate reports in the British media that pressure is mounting on Dublin.

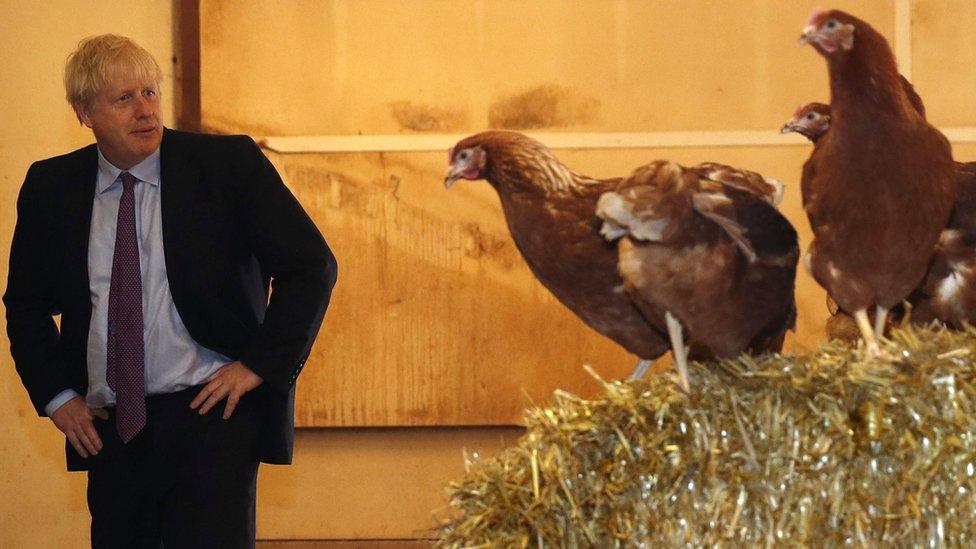

Boris Johnson's first speech as prime minister in the House of Commons

The sources agree that what Mr Johnson is doing, in calling for the binning of the backstop as a first step to allow negotiations, is taking any pressure off Dublin that may have been forthcoming down the line.

That's because after the lengthy negotiations that went into the withdrawal agreement to accommodate the British red lines, the EU-27 are not going to suddenly offer Boris Johnson a substantially better deal than the one they gave Theresa May.

Another official says the British government's attitude "is consistent with several of their fundamental misconceptions; such as the EU needs us more than we need them; the damage of a no-deal Brexit is symmetric and affects the EU and the UK both equally: that German car manufacturers will put pressure on Angela Merkel and Ireland is so small it won't be able to withstand pressure".

Compromise?

The Irish authorities have published a number of reports which highlight how drastic a no-deal Brexit would be be for the Republic.

The governments summer economic statement suggested there could be 55,000 fewer jobs and a 3% drop in growth.

If and when serious talks start in a few weeks time, Fergus Finlay, a newspaper columnist with the Irish Examiner who has experience as an Irish official of negotiations with the British on Northern Ireland, says "until a compromise is visible, there must be no compromise".

He says the Irish government has "not been guilty of any triumphalism", but is seeking to defend its interests and those of Northern Ireland.

Irish minister Helen McEntee and the French Minister for Europe AmŽile de Montchalin stand on either side of the border on 19 July

There have also been mutterings in the British media that Leo Varadkar is coming under domestic political pressure to alter his government's position on the backstop.

That is simply not the case.

The taoiseach leads a minority government that is dependent on the support of the main opposition party in a confidence and supply arrangement.

Indeed, there is a widespread consensus in the Dáil (lower house of parliament) that the government must hold the line on the backstop to prevent a hard border and to protect the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that helped to bring about peace on the island.

But there is also a view among a minority of commentators that Dublin is not cognisant enough of UK sensitivities and political needs.

They argue that the backstop designed to avoid a hard border might result in that very eventuality if the UK leaves the EU without a deal.

The new prime minister visited Wales on Tuesday

Ministers and officials in Dublin suspect that the prime minister may be more interested in an early general election, than in making the necessary compromises to reach a deal to allow the UK leave the EU on 31 October.

They, like everybody else, are keeping an eye on the evolving parliamentary arithmetic at Westminster.

And although Boris Johnson has only been a short time in his new job, the next few weeks and months promise to be very interesting and uncertain as bluffs have to be eventually called by all sides.

- Published16 October 2019

- Published30 July 2019