Franco exhumation: Dictator's move stirs fury in divided Spain

- Published

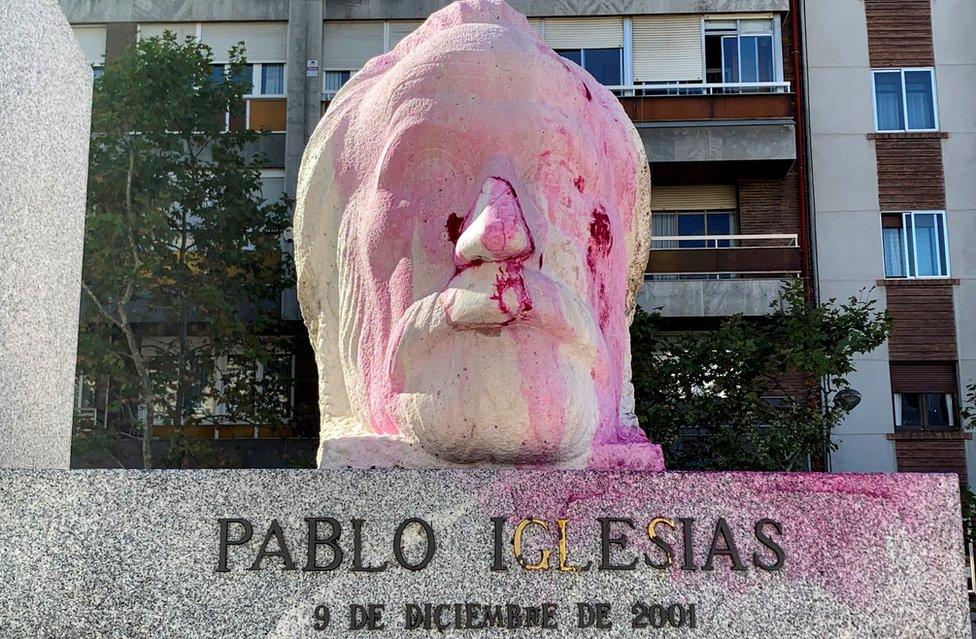

Paint was daubed on this statue in Madrid commemorating the founder of Spain's ruling Socialist party, Pablo Iglesias

"Long live Franco" and "Desecrators" were painted in graffiti on the Madrid statue of the founder of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, Pablo Iglesias, on Thursday.

In another part of the city, a monument dedicated to the international brigades, who fought against Franco's troops during the Spanish Civil War, was defaced with pro-Franco slogans and the words "Death to communists."

The link to the exhumation and transfer of the remains of General Francisco Franco, overseen by today's Socialist government, was obvious. Yet such a response hardly chimed with acting Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez's aim in carrying out the procedure.

Franco's coffin was carried out of the mausoleum

In his statement after the exhumation at Madrid's vast Valley of the Fallen, Mr Sánchez described it as "another step in the reconciliation" of Spaniards, so many of whom had been divided into left and right by the civil war and ensuing dictatorship.

Yet the decision to move Franco's body to a quiet cemetery was always likely to provoke a fierce reaction from some quarters. And so it proved.

Franco supporters gathered outside the dictator's new resting place in Madrid's El Pardo neighbourhood

A swastika pendant around his neck, Chema Quijada gathered with other Franco supporters at Mingorrubio cemetery to protest against the initiative.

"Ever since the transition [to democracy] until now, all the political parties have betrayed us," he said. "They have falsified history. They don't want new generations to understand Spain's history."

There was also discontent on the left at how the government had managed the occasion, particularly the presence of Justice Minister Dolores Delgado at the exhumation as a legal witness.

There was anger that Justice Minister Dolores Delgado (R) attended the exhumation as a legal witness

"I don't fully understand what members of the government and other representatives of our democracy are doing, solemnly attending what is clearly a tribute to the dictator by his relatives and other fascists," tweeted Alberto Garzón, leader of the United Left coalition.

But amid the misgivings about how the exhumation had been carried out, there was also strong support for it.

Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz, a 93-year-old historian, felt relief at Franco's transfer from the Valley of the Fallen. As a young man he escaped from the site after being sent there to do forced labour.

"I don't see why a dictator of the group that included Hitler, Mussolini and others had to be buried in Spain in a monument," he said. "I have been feeling shame all this time."

Historian Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz was sent to do forced labour at the Valley of the Fallen when he was young

He added: "It's about time."

Yet many of those who followed events live on television in bars and homes across Spain on Thursday did not feel nearly as strongly as either Sánchez Albornoz or the pro-Franco demonstrators.

A recent poll published by El Mundo showed that only 24% of people were "not at all in agreement" with the exhumation, while 32% were "totally in agreement".

The remainder either felt not very strongly about it, or even had no opinion on the matter.

It is still not clear how the government will repurpose the Valley of the Fallen now that Franco has been removed from it.

But for historical memory campaigners there are other major pending issues: the prosecution of Franco-era officials suspected of human rights abuses who are protected by an amnesty law; and the more than 100,000 unmarked graves across the country still containing Franco's victims.

It could be that the Sánchez administration, rather than simply riling the far-right by exhuming the country's dictator, has raised the expectations of many others.

- Published24 October 2019