Spain feels Franco's legacy 40 years after his death

- Published

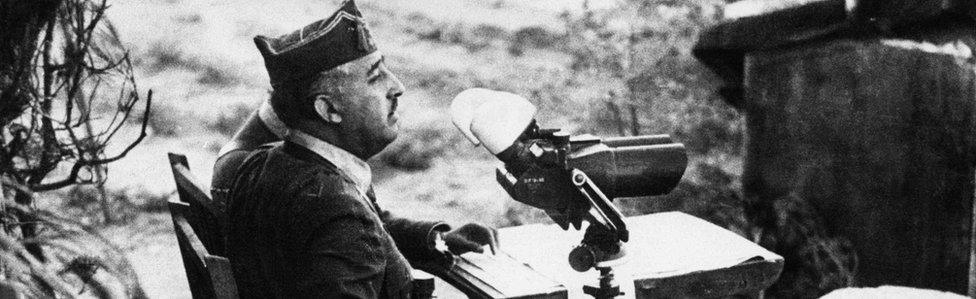

Gen Franco's dictatorship came to an end in 1975

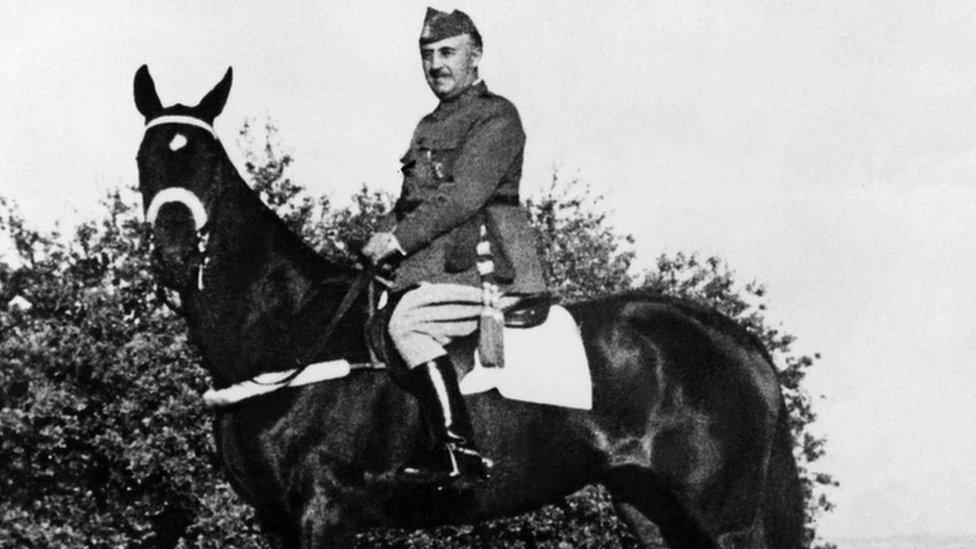

Spain's Gen Francisco Franco fought a brutal war against democracy with the aid of Hitler and Mussolini and thereafter presided over a regime of state terror and national brainwashing through the controlled media and the state education system.

His investment in terror imbued the collective Spanish psyche with a determination never again to undergo such civil conflict or to suffer another dictatorship.

That remains the case to this day, exactly 40 years after his death.

However, unlike Hitler's Germany or Mussolini's Italy, where external defeat led to denazification processes, there was no equivalent in Spain - and the shadow of his regime still bedevils politics.

Franco's vengeful triumphalism had been fostered in the military academies, where officer cadets were trained to regard democracy as signifying disorder and regional separatism.

Colonel Antonio Tejero brandished a gun as he tried to take over Spain's parliament

As the dictatorship was rapidly dismantled, some of its senior military defenders did not share the massive political consensus in favour of democratisation and so endeavoured to turn back the clock at several moments in the late 1970s and, most dramatically, in the attempted coup of Colonel Antonio Tejero on 23 February 1981.

Death of a dictator

November 1975: Franco (1892 - 1975) lies in state at the Pardo Palace in Madrid.

General Franco, known as El Caudillo (Leader), died on 20 November 1975

In his last message to the nation the dictator said: "I ask pardon of all my enemies, as I pardon with all my heart all those who declared themselves my enemy, although I did not consider them to be so"

Prince Juan Carlos was sworn in as King of Spain on 22 November 1975

Witness: Death of Franco

After the defeat of the coup in 1981, the attitudes of the armed forces were changed by Spain's entry into Nato in 1982, which shifted their focus outwards from their previous obsession with the internal enemy.

Scarred by the horrors of the civil war and the post-war repression, during the transition to democracy Spaniards rejected both political violence and Franco's idea that, by right of conquest, one half of the country could rule over the other.

However, what was impossible in a democracy was a counter-brainwashing.

Residual support

Moreover, especially in his later years, Franco did not rule by repression alone: he enjoyed a considerable popular support. There were those who, for reasons of wealth, religious belief or ideological commitment, actively sympathised with his military rebels during the civil war.

Then, from the late 1950s onwards, there was the support of those who were simply grateful for rising living standards.

Although in the many national, regional and municipal elections that have been held in Spain since 1977, openly Francoist parties have never gained more than 2% of the vote, a residual acceptance of the values of the Franco dictatorship can be found in the ruling conservative Popular Party and its electorate.

Pro-Franco nationalists have never attracted much support in Spain since his death

Accordingly, no government has ever declared the Franco regime to be illegitimate. It was not until 2007 that the Law of Historical Memory made tentative efforts to recognise the sufferings of the victims of Francoism.

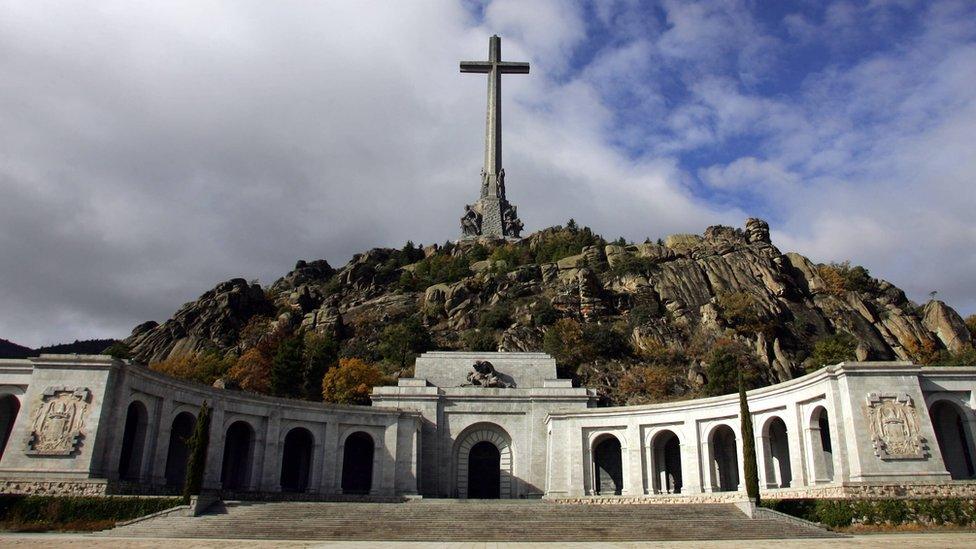

Equally slow has been the process of removing the symbols of the dictatorship, the Falangist equivalent of the swastika - its emblem of the yoke and arrows - on church walls, street names commemorating Franco's generals and, above all, the huge basilica and towering cross of the Valley of the Fallen where the dictator is buried.

Franco's rule

1936: After coup, right-wing military leaders capture part of Spain leading to three-year civil war

1939: Gen Franco leads Nationalists to power, remains neutral in World War Two

First decade of rule sees continued oppression and killing of political opponents

20 November 1975: Franco dies; Franco-era crimes pardoned in 1977 under amnesty law

2007: Historical Memory law passed on removing symbols of Franco's rule

2008: Judge Baltasar Garzon investigates disappearance of tens of thousands of people during Franco era

Today, along with the still open wounds of the civil war and the repression, two other shadows of the dictatorship hang over Spain - corruption and regional division. The Caudillo's rigid centralism and its brutal application to the Basque Country and Catalonia had left more powerful nationalist movements there than had ever existed before 1936.

The democratic constitution of 1978 enshrined rights of regional autonomy for Catalonia and the Basque Country with which the right has never been comfortable.

Mass pressure in Catalonia for increased autonomy met with an intransigence that has fuelled a campaign for independence.

Drawing on a residual Francoist centralism, the Popular Party has fomented hostility to Catalonia in particular for electoral gain. The consequent divisiveness, at times bordering on mutual hatred, is one of the most damaging legacies of Francoism.

Support for Catalan independence has been fuelled by Madrid's perceived neglect of the region

The other is the corruption that permeates all levels of Spanish politics. Needless to say, there was corruption before Franco and corruption is not confined to Spain. Nevertheless, it is true that the Caudillo used corruption both to reward and control his collaborators.

Recent research has uncovered proof of how he used his power to enrich himself and his family. In general, the idea that public service exists for private benefit is one of the principal legacies of his regime.

It will thus be many years before Spain is free of Franco's legacy.

Paul Preston is Professor of Contemporary Spanish Studies at the London School of Economics and leading writer on Franco. Among his books are Franco: A Biography and The Spanish Holocaust

- Published19 November 2015

- Published7 July 2015

- Published28 September 2015

- Published18 December 2012

- Published1 November 2014

- Published1 October 2013

- Published19 July 2011

- Published12 December 2022