General election 2019: Divisive UK campaign reaches climax

- Published

The UK prime minister shakes hands with President Trump but spent little time with him in public

The penultimate week of campaigning has been as frantic as you would expect and it has been punctuated, of course, by two events.

The first was the tragic murder of two young Cambridge graduates in a dramatic attack in London by a man previously convicted on terrorism charges.

The second was the brief visit of US President Donald Trump.

In the 2017 general election, the horrific mass casualty suicide attack at a concert in Manchester completely eclipsed the campaign for several days.

This does not appear to have happened this time, although the anger of the father of one of the victims at what he saw as attempts by Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his allies to exploit the murders to sound tough on crime might have proved difficult for the Conservative Party had they not quickly changed their tone.

Trump barely tweets a word

As to Mr Trump's brief visit to the UK for the Nato summit, he seemed to be on his best behaviour and determined not to do or tweet anything that would make life hard for a prime minister he once referred to affectionately as "Britain Trump".

Trump on Johnson: "They call him Britain Trump"

It was pretty much mission accomplished. The president barely tweeted a word.

Treating the visiting president as if he were an embarrassing and distant relative, Mr Johnson was barely photographed side by side with the US leader, and there was no joint news conference.

He didn't even greet Mr Trump at the door of 10 Downing Street, instead waiting for him safely inside, away from photographers who might capture a friendly moment between the two men.

The main opposition Labour Party tried to use the visit to highlight concerns that, in any future post-Brexit trade talks, surely US companies would be interested in a share of the UK's enormous government-owned-and-run health sector - the much loved National Health Service (NHS).

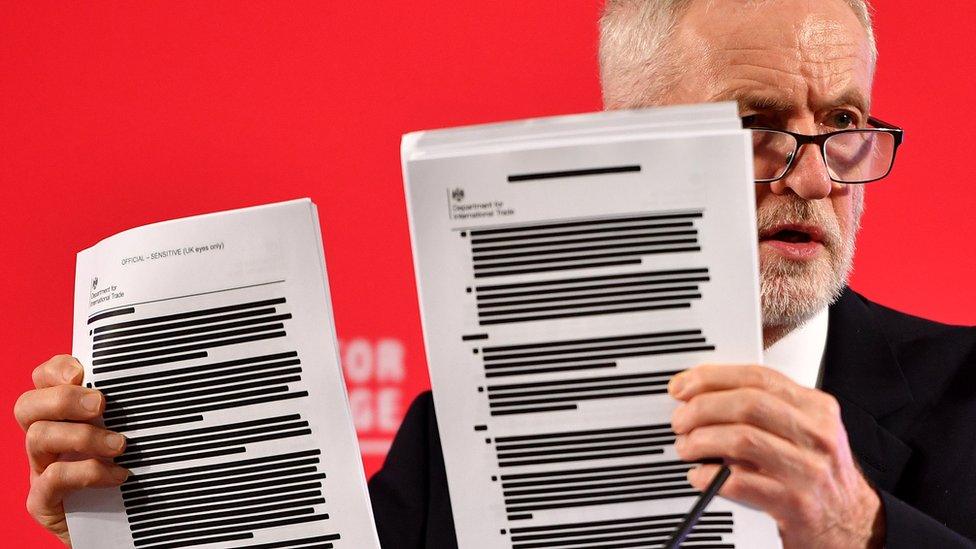

Jeremy Corbyn presents redacted government documents about US trade negotiations

Certainly voters are very concerned about the funding and running of the NHS, but it's not clear what they believe about the claims and counter-claims that the NHS will be up for sale post-Brexit.

Testing the Brexit theory

This week also marks the end of my mini-election tour of the UK, which has taken me to Northern Ireland, Scotland and finally to Birmingham in the English Midlands.

I went there to test the theory, mentioned earlier, that Mr Johnson will win this election if:

the Leave vote from 2016 is less fractured than the Remain vote: in other words that a majority of the 17.4 million who voted Leave back the Conservatives while the 16.8 million Remain votes are more divided among various parties

white, working class voters, who traditionally support Labour, switch to the Conservatives because they are pro-Brexit and because they consider the current Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn far too left-wing

So what did I find?

In short, there was plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest the theory has some merit.

At the Longbridge Social Club, just about everyone I met had voted to leave the European Union and thought Mr Corbyn too left-wing.

This working men's club was set up to serve as a place to relax for the men who worked at what was once one of Europe's biggest car factories. The factories have now been replaced by a college, a shopping centre, a retirement home and other developments.

I found similar while walking down the main high street in one of Birmingham's eight parliamentary constituencies, namely people identifying themselves as working-class switchers.

None of this is scientific and much of the switching predicted in 2017 in the end didn't happen. So we'll see.

At this point perhaps, having largely focused on Labour and the Conservatives, I should mention Britain's third largest, and out-and-out anti-Brexit Party, the Liberal Democrats.

In a country polarised so profoundly on Leave/Remain lines it had been thought they might do rather well, but so far the opinion polls suggest only modest gains.

Their leader, Jo Swinson, has been asked repeatedly, in that brutal way that happens in elections, why people seem to like her less the more they see of her, and whether it was a mistake to have made their central policy reversing Brexit without necessarily first having another referendum.

Would it be different if they had a different leader and had they campaigned for a second referendum?

Who knows? Maybe, maybe not. Maybe at times of national crises, voters are drawn to the two big parties even when they don't even like them very much.

Again, we'll see on 12 December.

A high stakes election

In terms of broader thoughts, my road trip has reminded me what a country of contrasts and diversity the UK remains.

People are both remarkably friendly and - many of them - also immensely angry. Parts of the country are stunningly beautiful, both in terms of scenery and architecture, while other parts look like they could really use some tender loving care.

Some places are strikingly youthful, while some offer a reminder that people are living so much longer these days. Boring it isn't.

All that said, despite the astonishingly high stakes, just how engaged people have been in this election is hard to gauge.

The only way to tell for sure, of course, will be voter turnout next Thursday. And here to help place next week's result in context is this little table:

68.7%General election turnout 2017

83.9%Highest ever election turnout (1950)

59.4%Lowest ever election turnout (2001)

72.7%EU referendum turnout (2016)

Finally, it's hard not to help wondering whether this is an election that would actually be better to lose.

It sounds odd, but consider this. All the government's own forecasts suggest all forms of Brexit will be economically damaging, the country remains deeply polarised and the voters profoundly sceptical of not just the politicians but the whole political system.

Not perhaps the ideal time to be in power.

- Published6 November 2019

- Published23 November 2019

- Published22 November 2019

- Published17 November 2019

- Published9 November 2019