French reforms: Why France is resisting Macron's push on pensions

- Published

Firefighters set each other alight during a protest in the centre of Paris last month

The rolling transport strikes that crippled Paris through much of December and January have stopped, as empty pay packets post-Christmas took their toll. Instead there has been a change of tactic, with the more radical unions now planning sporadic days of action.

President Emmanuel Macron's bid to radically overhaul the post-war pension system reaches the National Assembly on Monday, ahead of a long period of debate.

The moment is being marked by a strike on the Paris metro and further protests on Thursday.

For the government, the pressure from the street has clearly diminished, even though the protests still draw tens of thousands.

But the bigger difficulty is with the broader public - polls continue to show a majority in favour of the strikes, and rejecting the government's handling of the reform.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The pensions issue has also served as a rallying-cry for all those with other grievances against President Macron.

How Macron changed his plans

The proposed law would radically overhaul the country's post-war pension system, merging the 42 existing private and public sector regimes into one, universal points-based system. Early retirement privileges enjoyed by some workers would come to an end.

President Macron started off with one kind of reform, then as the protests grew he tried to convert it into another.

The initial proposal, as sold to the public, was to create a fairer system by making everyone put into - and get out of - the same pension pot under the same rules. It was a "systemic" reform, to use the parlance.

But somewhere en route it also became a "parametric" reform. In other words the government decided that now was also the moment to shuffle the numbers around in order to ensure the system's long-term financial survival.

Somewhere in the change, the government decided it had to be written in that people were going to have to work for longer, retiring later in life.

"Macron pensions - it's No!" reads a transport worker's placard in Paris

This may have been eminently sensible, but it was not what the government had advertised. And the unions - even the "moderate" ones - got cross.

The number of French people who actually understand the pensions reform can probably be counted in fingers and toes.

What on earth, for example, is the difference between an age de pivot (age of pivot) and an age d'équilibre (age of balance)?

They both have something to do with the year you first claim your pension, and whether or not you get penalised or rewarded.

The government says it backed down in response to the protests, abandoning the pivot age in favour of the latter.

And yet no-one in France can figure out what that implies.

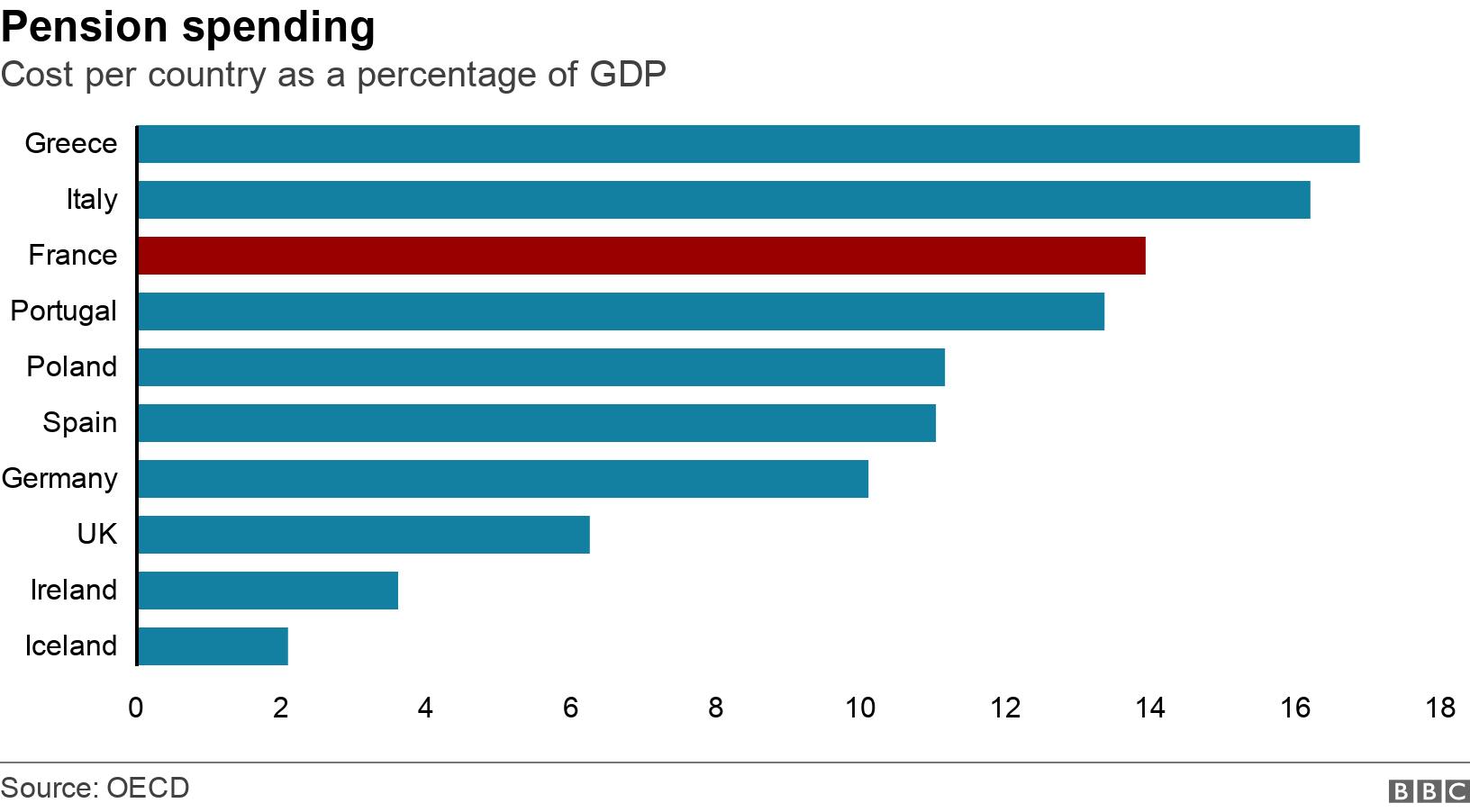

Meanwhile, the government has set up a working group to report on ways of balancing out the current €14bn (£11.5bn; $15bn) pensions deficit.

So what does any of it mean for France's workforce?

Who are the winners and losers?

Most public sector employees receive a lot of their pay in the form of bonuses.

But teachers just get it straight. In the new universal pension system that's not good, because for the first time bonuses will be used in the calculation of who gets what.

Paris opera orchestra stages free concert against pension reform

So teachers fear they will lose out. The government says it will boost teachers' salaries to compensate.

But will it? And by how much?

Farmers, mothers and the low-paid are all said to be future beneficiaries of the new system.

Metro and train drivers will suffer, because they see the end of their special status.

But some other special statuses will survive, like for the army and police. Lawyers will be allowed to keep their special caisse (fund) with its massive surplus - for a while.

What happens now?

The National Assembly will now prepare to take up the baton on this mother of all reforms.

There are technically two laws going before parliament.

One is an ordinary law, and one is an "organic" law. The far-left opposition have tabled 20,000 amendments in committee; the State Council has ruled that in several aspects the government's intention to resort to decrees to implement the reform needs clarification.

For six weeks in December and January the Paris transport system was badly disrupted by union protests against the reforms

Is it any wonder that the pension reforms have triggered the longest opposition movement since President Macron came to power?

The key point is not that people necessarily dislike the idea of a universal points-based system.

After all, as the president says, its much-vaunted prime characteristic - and what distinguishes it from the dreaded Anglo-Saxon systems - remains intact.

It is and will be a single "share-out" system in which workers pay in and pensioners take out. There are no scary pension funds.

No, the key point about the reform is that most people simply find it impossible to make head or tail of.