Navalny and Russia’s arsenal of exotic poisons

- Published

An emergency airlift to Berlin from Omsk was organised for Mr Navalny

Several prominent critics of Kremlin policies - ex-spies, journalists and politicians - have been poisoned in the past two decades.

In the UK, two Russian ex-secret service agents were targeted: Alexander Litvinenko fatally with radioactive polonium-210 in 2006, and Sergei Skripal with the toxic nerve agent Novichok in 2018. The Kremlin denied any involvement.

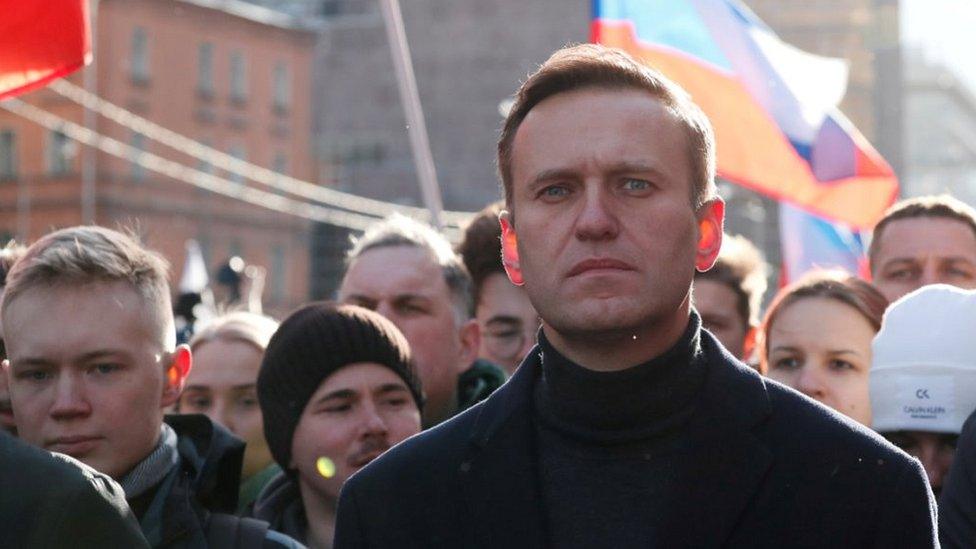

Alexei Navalny, who has been physically attacked before, appears to be the latest victim. Yet much remains unclear.

Mysterious poisonings involving Russians often remain mysterious - a distinct advantage for assassins, compared with say an old-fashioned shooting in the street.

Prof Mark Galeotti, a Russia expert at the Royal United Services Institute, told the BBC that "poison has two characteristics: subtlety and theatricality".

"It's so subtle that you can deny it, or make it harder to prove. And it takes time to work, there's all kinds of agony, and the poisoner can deny it with a sly wink, so everyone gets the hint."

Thorn in Kremlin's side

Alexei Navalny is Russia's best-known anti-corruption campaigner and opposition activist. His slick, hard-hitting videos on social media have drawn many millions of views, and made him a thorn in the side of the Kremlin.

For years Mr Navalny has rallied his supporters across Russia

A victim poisoned before a long flight can be stuck in the air long enough for the assassin to make an easy getaway. Mr Navalny, 44, fell acutely ill on a flight from Tomsk in Siberia on 20 August - so ill that it had to be diverted to Omsk.

Russian investigative reporter and Putin critic Anna Politkovskaya, shot dead in 2006, claimed to have been poisoned on a flight to the North Caucasus in 2004, when she felt sick and fainted.

Similarly, a slow-acting poison - polonium-210 - killed Litvinenko excruciatingly and it was weeks before the rare toxin was identified. As an alpha-particle emitter its radiation was not detected by a Geiger counter.

The two alleged Russian killers - state agents, according to the subsequent UK inquiry - had plenty of time to fly home unsuspected.

Mr Navalny has accumulated many enemies in Russia, not just among supporters of President Vladimir Putin, whose United Russia party he labels "the party of crooks and thieves". Mr Putin was a secret service officer in the Soviet KGB before becoming president in 2000.

Mr Galeotti says that in this case "the Russian state seems to have been caught off-balance, which implies it wasn't a centrally planned operation". "This suggests it was the act of a powerful Russian, but not necessarily the state."

Nerve agent symptoms

Now fighting for his life in Berlin's Charité hospital, Mr Navalny is in an induced coma, being treated for "poisoning with a substance from the group of cholinesterase inhibitors".

The hospital says the specific toxin remains unknown - tests are being done to identify it. But the poison's effect - inhibition of the enzyme cholinesterase in the body - "was confirmed by multiple tests in independent laboratories".

That is the effect of military nerve agents, such as sarin, VX or the even more toxic Novichok. They interfere with the brain's chemical signals to the muscles, causing spasms, shortness of breath, heart palpitations and collapse.

Germany has imposed tight security at Berlin's Charité hospital

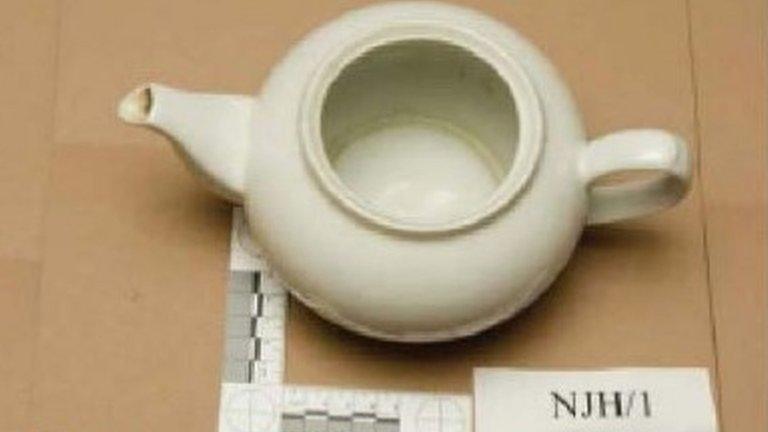

Mr Navalny's spokeswoman Kira Yarmysh suspects that poison was slipped into the cup of black tea he drank at a Tomsk airport cafe. He had not eaten anything before the flight, she says.

That ominously echoes the case of Litvinenko, who drank poisoned tea in a London hotel.

A prominent anti-Putin activist based in the US, Vladimir Kara-Murza, says he suffered similar symptoms to Mr Navalny's in 2015 and 2017. His alleged poisoning remains a mystery.

Poison, he told the BBC, "is becoming sort of a favoured tool of Russian security services" and "a sadistic tool".

"It is excruciating to go through this... I had to learn to walk again after the first poisoning and coma."

When the plane landed in Omsk on 20 August medics rushed Mr Navalny into intensive care already comatose, and put him on a ventilator.

Delaying investigation

Mr Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov says the Berlin doctors' diagnosis of poisoning is not yet conclusive, so it is too early to launch an official investigation. Earlier he said the Kremlin wished Mr Navalny well, when permission was granted to fly him to Berlin.

There is speculation that the delay in Omsk, before Mr Navalny's transfer to Berlin, could have helped erase traces of the poison.

The Omsk doctors have also been criticised for suggesting that the problem was a "low blood sugar level" and apparently failing to spot nerve agent symptoms.

Dr Konstantin Balonov, a US-based anaesthesiologist, told BBC Russian that that failure was "strange, to say the least". Moscow toxicologists also consulted the Omsk doctors and "they must have concluded that it was a toxin from that [chemical] group".

There are suspicions of a cover-up, as unidentified police were quickly on the scene, blocking access. The doctors insisted that no poison was detected in Mr Navalny's urine.

Read more on related topics:

It has emerged that atropine - an antidote to nerve agent - was administered in Omsk.

But Mikhail Fremderman, previously an intensive care specialist in St Petersburg, said that "in poisoning cases such as this, atropine must be given intravenously, for a long period". That may not have happened in Omsk, he told BBC Russian, adding that the medical data has not been released.

Spectrum of chemicals

Prof Alastair Hay, a leading British toxicologist and chemical weapons expert, says this type of nerve agent is at the "extremely toxic" end of a broad spectrum of organophosphates.

That large group of possible poisons makes the agent already hard to identify. Some much milder organophosphates are used in insecticide and in medical therapies.

"It only requires a small dose to kill someone, which can be effectively disguised in a drink," he told the BBC.

Work carried out at Porton Down is normally highly classified

There are yet more advantages, from the assassin's point of view. "A simple blood test doesn't tell you what the agent is - you need a more sophisticated test, very expensive equipment. Many hospital labs don't have that expertise," Prof Hay said.

In the UK, that capability is restricted to Porton Down, a high-security chemical and biological research centre.

The UK and Russia are among 190 signatories to the global Chemical Weapons Convention, which bans chemical weapons use and research, beyond small quantities allowed for developing antidotes and protective equipment.

After the Cold War Russia destroyed its vast chemical weapons stockpile - about 40,000 tonnes - under international supervision, Prof Hay noted.

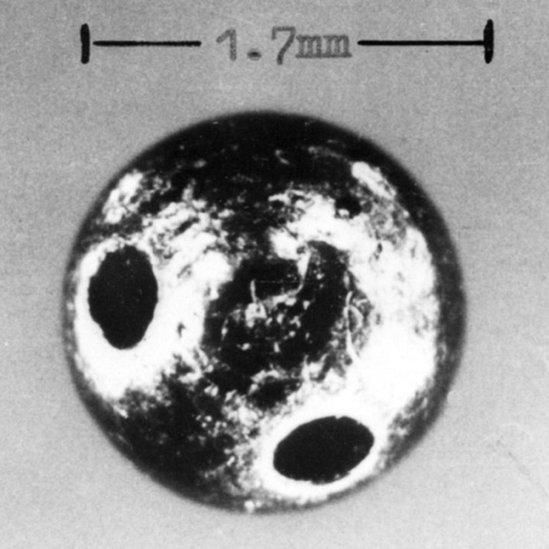

A biopsy on Georgi Markov revealed this tiny pellet, believed to have contained ricin

Exotic chemicals were also used in some Cold War "hits" - for example the notorious umbrella killing of Bulgarian anti-communist journalist Georgi Markov in London in 1978. At the time Bulgaria was an ally of the Soviet Union.

The suspected poison was ricin, released from a tiny pellet found in the autopsy. The killer had stabbed it straight into Markov's bloodstream with the umbrella - a far more potent delivery method than if he had swallowed it.

- Published16 February 2024

- Published11 November 2014

- Published28 July 2015

- Published25 August 2020

- Published19 December 2018

- Published3 February 2018

- Published28 June 2019

- Published17 March 2024