Viewpoint: Why Turkey is flexing its muscles abroad

- Published

In recent years Turkey has launched three incursions into Syria and become increasingly involved abroad

Immediately after a long-simmering conflict in the South Caucasus burst into open warfare late last month, Turkey came to the aid of its Turkic allies in Azerbaijan. It has supplied arms and, allegedly, fighters transferred from Syria, although that has been denied in Ankara.

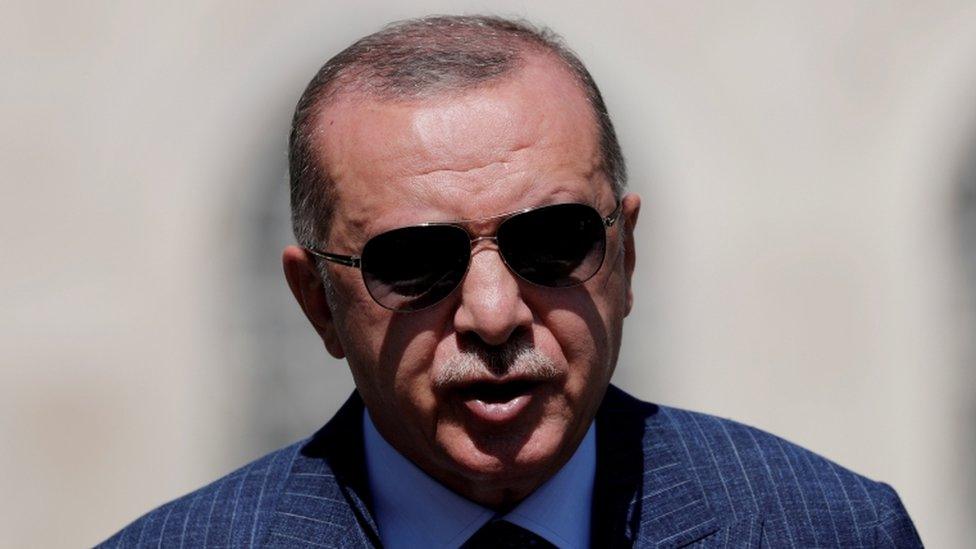

Unlike most outside powers that called for an immediate ceasefire, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan told Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev to fight on.

The Caucasus is only the latest venture for a more muscular Turkey, whose military engagements have stretched from Syria across the Mediterranean.

Where has Turkey become involved?

In the last few years, Turkey has:

launched three military incursions into Syria

sent military supplies and fighters to Libya

deployed its navy to the Eastern Mediterranean to assert its claims in the region

expanded its military operations against Kurdish PKK rebels in northern Iraq

sent military reinforcements to Syria's last rebel-held province of Idlib

recently threatened a new military operation in northern Syria to confront "terrorist armed groups".

Turkey also has a military presence in Qatar, Somalia and Afghanistan and maintains peacekeeping troops in the Balkans. Its global military footprint is the most expansive since the days of the Ottoman Empire.

What is behind Turkey's new foreign policy?

Turkey's reliance on hard power to secure its interests is the cornerstone of its new foreign policy doctrine, in the making since 2015.

The new doctrine is deeply suspicious of multilateralism and urges Turkey to act unilaterally when necessary.

It is anti-Western. It believes that the West is in decline and Turkey should cultivate closer ties to countries such as Russia and China.

President Erdogan has been outspoken on Turkish drilling rights in the Eastern Mediterranean

It is anti-imperialist. It challenges the Western-dominated World War Two order and calls for an overhaul of international institutions such as the United Nations, to give voice to nations other than the Western countries.

The new foreign policy doctrine views Turkey as a country surrounded by hostile actors and abandoned by its Western allies.

Therefore, it urges Turkey to pursue a proactive foreign policy that rests on the use of pre-emptive military power outside its borders.

This is a far cry from Turkey's previous focus on diplomacy, trade and cultural engagement in its relations with other nations. The change is a function of several domestic and international developments.

What changed?

Turkey's new doctrine began to take shape in 2015, when the ruling AKP lost its parliamentary majority for the first time in over a decade due to the rise of the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP).

To regain the ruling party's majority, Mr Erdogan formed an alliance with nationalists both on the right and left.

They backed him when he resumed the fight against the Kurdish rebels.

How focus turned to Kurds

Turkey's conflict with the PKK - Kurdistan Workers' Party - had to a large extent stopped after the group's imprisoned leader, Abdullah Ocalan, called for a ceasefire with the Turkish state in 2013.

Despite their ideological differences, both the far-right nationalist MHP and neo-nationalists on the left support a heavy-handed approach to the Kurdish problem. They also prioritise national security at home and abroad and espouse strong anti-Western views.

With their support, Mr Erdogan also switched the country's parliamentary system to a presidential one granting him sweeping powers.

This alliance with the nationalists and consolidation of his power became the key driving factor behind Turkey's unilateralist, militaristic and assertive foreign policy.

The failed 2016 coup played a key role in this process.

How coup changed the narrative

According to President Erdogan, the botched coup was orchestrated by former ally Fethullah Gulen, an Islamic cleric in self-exile in Pennsylvania, and it did several things to pave the way for Turkey's militaristic foreign policy.

It strengthened Mr Erdogan's alliance with the nationalists.

His sweeping purge of civil servants suspected of having links to the Gulen movement led to some 60,000 people being fired, jailed or suspended from the armed forces and judiciary, and some other state institutions.

The failed coup ended up bolstering President Erdogan's position and his alliance with nationalists

The void left by the purges was filled with Erdogan loyalists and nationalist supporters.

The failed coup also strengthened the nationalist coalition's narrative that Turkey was besieged by domestic and foreign enemies and that the West was part of the problem. That justified unilateral action, supported by pre-emptive deployment of hard power beyond Turkey's borders.

How approach changed in Syria

The Assad regime's decision to give a free hand to Syria's Kurds in the north led to an autonomous Kurdish zone along Turkey's border and in 2014 the US decided to airdrop weapons to the Kurdish militants, considered to be a terrorist organisation by Turkey. This all fed the narrative that Turkey had to act alone and deploy military forces to protect its borders.

The failed coup also paved the way for consolidation of power in Mr Erdogan's hands.

Through purges he hollowed out institutions, sidelined key actors in foreign policymaking such as the foreign ministry, and emasculated the military, which had put a brake on his previous calls to launch military operations in neighbouring countries.

Before the coup attempt, he had signalled his intention to launch a military operation into Syria to stem the "terrorist threat" emanating from the Kurdish militias there. But Turkey's military, which had traditionally been very cautious about troop deployment outside Turkey's borders, was opposed.

A few months after the coup attempt, President Erdogan got his wish. Turkey launched its first military operation into Syria to curb the influence of the Kurds in the north in 2016 and two more incursions after that.

The move was applauded by the president's nationalist allies, who fear an independent Kurdish state built with US help along its border. To curb Kurdish influence and counterbalance the US presence in Syria he worked with Russia.

How Turkey switched focus to Libya and E Mediterranean

Libya became another theatre for hard-power tactics.

In January, Turkey stepped up military support to Libya's UN-backed government of Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj, to stop an offensive by forces allied with Gen Khalifa Haftar.

BBC Africa Eye investigates secret arms shipments into Libya.

Turkey's primary goal in Libya was to secure the Serraj government's support in a matter important to Mr Erdogan's nationalist allies: the Eastern Mediterranean.

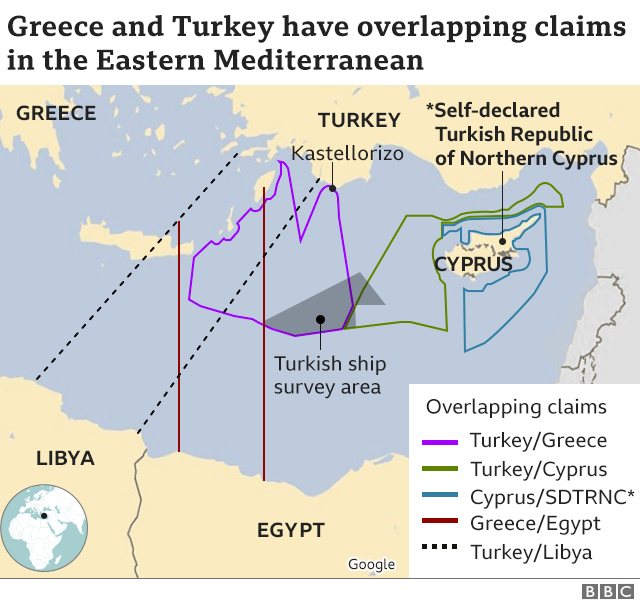

Turkey has been at loggerheads with Greece and Cyprus over energy drilling rights off the coast of the divided island of Cyprus and maritime boundaries in the area.

Ankara signed an agreement on maritime boundaries with Mr Serraj in November in return for military support to the Tripoli government.

Mr Erdogan's aim was to redraw maritime borders in the Eastern Mediterranean which, in his opinion, provided disproportionate advantages to Turkey's arch-enemies - Greece and the Republic of Cyprus.

Meanwhile, Turkey sent warships to escort its drilling ships in the Eastern Mediterranean, risking a military confrontation with its Nato partner Greece.

Has it been a success?

Turkey's assertive policy in Syria, Libya and the Eastern Mediterranean has not yielded the results that President Erdogan's ruling coalition hoped for.

Turkey could not entirely clear Kurdish militia forces from its border with Syria. Neither Ankara's maritime agreement with Libya nor its actions in the Eastern Mediterranean have changed the anti-Turkey status quo in the region.

On the contrary, Turkey's military involvement in these conflicts hardened anti-Erdogan sentiment in the West and unified a diverse group of actors in their resolve to oppose Turkish unilateralism, eventually forcing Turkey's leader to back down.

Turks have taken to the streets in support of Azerbaijan during the Karabakh conflict

A similar fate awaits Turkey's involvement in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, which is already seeing the emergence of a more forceful Russian response and a Russian-Western front against Turkey's support for Azerbaijan.

What next?

But Mr Erdogan's nationalist allies want him to fight on. A prominent neo-nationalist, Retired Rear-Admiral Cihat Yayci, argued that Greece wanted to invade western Turkey and urged Mr Erdogan to never sit down with Athens to negotiate.

And the president has little option but to listen to him. As he loses ground in opinion polls, the nationalist sway over his domestic and foreign policies only increases.

Gonul Tol is Director of the Center for Turkish Studies at the Middle East Institute in Washington DC

- Published24 March

- Published26 March 2020

- Published30 September 2020