Peter Florjancic: Story of ski-jumping inventor who escaped the Nazis

- Published

"The inventor must have a calm head, he must always observe everything," Florjancic said

Peter Florjancic, the Slovenian inventor who died last week aged 101, once remarked that even Alfred Hitchcock would struggle to make a film about his life.

He was at various times an Olympic athlete, film actor, author, and friend of the rich and famous. But throughout his extraordinary life he had one chief passion: the everyday.

Florjancic was fixated on inventing ways to make life easier, safer and, where possible, a little more stylish. And while he is far from a household name, his inventions have almost certainly found a place in millions of homes.

Florjancic was born in the fashionable resort town of Bled in 1919. "Most of the hotels were in my family's ownership," he told Kongres Magazine. "The castle was owned by my uncle [and] my grandfather owned Hotel Triglav and Hotel Union. Bled was practically ours!"

His family's status led to a colourful childhood in which he met the various celebrities who stayed in the town. He once welcomed the Yugoslav queen to Bled by playing the accordion for her in full national dress.

There were signs of the ingenuity that would mark his later career as an inventor, too. He recalled creating an early sweatband aged just six. "We [would] roll around in the mud and grass. My whole face was dirty," he said. "So I cut a sock, put it on my hand and wiped my face with it and my face was clean again."

Florjancic was born - and later returned to - the picturesque Slovenian town of Bled

Florjancic was a talented athlete and, owing to his youth in Slovenia's mountainous resort region, skiing was an early passion. At just 16, he became the youngest member of the Yugoslav Olympic team when he competed in the ski jump at the 1936 Winter Games in Germany.

The Games were opened by Adolf Hitler and senior figures of the emerging Nazi regime often watched the events. After competing in the ski jump, Florjancic shook the hand of Heinrich Himmler, the man who became head of Nazi Germany's infamous SS.

But his Olympic handshake was far from his last encounter with the regime. Many Slovenian men were mobilised into the German army during World War Two, and Florjancic was conscripted to fight on the Russian front in 1943.

Unwilling to go to war he deserted and staged a daring escape to neighbouring Austria under the guise of a skiing holiday. He was pursued by the Gestapo and - with a friend - faked his own death in an avalanche on the slopes of the Hahnenkamm mountain. Somehow, the plan worked.

The 1936 Winter Olympics was held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Germany and opened by Adolf Hitler

"It was a real masterpiece," his friend and biographer, Edo Marincek, told the BBC. "He escaped with his friend who he later learned was providing information on the Gestapo to the US."

"They staged their deaths in an avalanche and then skied across a glacier from Austria to neutral Switzerland," Marincek said. "If the Gestapo had discovered that Peter had deserted they would have killed his family, so no one knew about the escape. On the island [in Bled] the locals even held a funeral for him."

Florjancic was granted asylum at a refugee camp in Bern, and it was there that he made his first real breakthrough. He designed a wooden weaving machine that could be used by disabled people, such as wounded soldiers, and sold the patent to a timber company for 100,000 Swiss francs.

"It was enough to buy three luxury houses," he told the BBC in 2011. It would be wrong to suggest the money didn't change him, or at least his quality of life.

Florjancic revelled in the glamour of Davos and Zurich, where he met his wife Verena. "He's got this amazing imagination and there are so many things he wants to discuss," the model and actress later told Deutsche Welle. "He's interested in everything."

In 1946, he took his wife and young daughter to Monte Carlo on holiday and stayed for more than 13 years. A poolside meeting with Ilhamy Hussein Pasha, an associate of King Farouk of Egypt, led to many years of collaboration and - significantly - major financial backing for his inventions.

"He understood innovation and also funded my mistakes," Florjancic later wrote.

Florjancic (far right) appeared in the 1957 film The Monte Carlo Story

One of his major successes came in Monte Carlo when he invented the compact perfume spray that is still in use today. Prior to this, most perfume was dispensed through a tube connected to a large rubber bulb. "I noticed how the women were practically taking a gasoline pump out of their bags," he told Deutsche Welle. "You just have to watch people."

His life in Monte Carlo was notable for the people he spent time with. Among his associates there were Frank Sinatra, Orson Welles, Salvador Dali, Coco Chanel and a young Audrey Hepburn. He even appeared in the 1957 film The Monte Carlo Story alongside actress Marlene Dietrich.

"I was at the right place at the right time," he later said. "They were always interested in my story. The story of my escape. I was always telling my story."

Other notable lives in profile:

Florjancic then travelled extensively and spent time living in France, Italy and Germany among many other countries. "Drop me anywhere in the world and in a year's time I'll entertain you there at my house," Edo Marincek recalls him saying.

Marincek's biography of Florjancic, Jump into the Cream, sold well in Slovenia. In the book, the inventor reflects on his long life and notes: "I've had five citizenships, 43 cars and the longest passport. The profession of inventor forced me to spend 25 years in hotels, four years in cars, three years on trains, a year and a half on airplanes and a year on board of ships."

As well as the perfume atomiser, Florjancic's inventions include plastic ice-skates and the plastic photographic slide frame.

He also designed a treadmill for skiing and a cigarette lighter with a side ignition that was used in numerous James Bond films. "I patented 400 inventions, and 41 of them I managed to bring to life," he said.

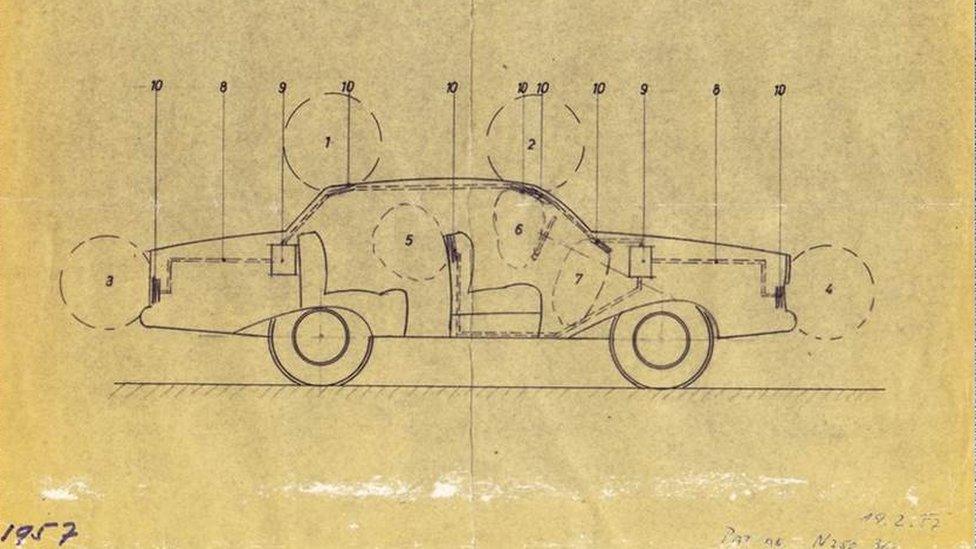

Florjancic's sketched prototype of the car airbag - a near miss

But not all of his efforts went to plan. In 1957, he sketched a prototype of the airbag but failed to overcome the issue of it repeatedly exploding. "I tried out my prototype, the valve slipped and it exploded. So I said 'bye bye', withdrew the patent, and forgot about it," he said.

Another nearly moment came when he almost invented the plastic zipper. "We washed it, and everything was perfect," he told the BBC in 2011. "Then we ironed the jacket - but we couldn't get the zipper open any more because it had melted. The champagne we had ready to celebrate we drank in sorrow, not in success."

The zipper was later re-invented by someone who used tougher materials, and Florjancic earned nothing. It was added to the list of near misses that also included drinking-straw holders and a shoe guard for drivers who wanted to prevent their heels from getting scuffed.

Despite these failures he made enough money, namely from a machine that could inject plastic into moulds, to live a life of relative luxury. Florjancic also stubbornly refused to plan for his retirement - insisting instead that he would work until the end.

He eventually returned to his native Bled in 1998. "I told my mother that I would come back to Bled to die. I thought that was going to be back in 2000," he joked in 2011.

He worked into his nineties, still creating and writing several books. "I'm only 90 years old," he told Deutsche Welle. "I'm still inventing things - I work all day long." In his later years he also worked to promote invention and innovation among young people.

"I've had a great life, so much living, full of all these things," he said. "Sometimes I wonder what I would do if I were born again. I reckon I would have done something similar."

- Published15 November 2020

- Published23 September 2020

- Published2 September 2018